TC’s Afghan Project: 25 Years in Afghanistan

Using education to change the world is nothing new at TC.

In its largest international education project to date, Teachers College spent 25 years in Afghanistan working under the United States Foreign Aid Program, to help the Afghans build a modern education system using a program called The Afghan Project. By creating new textbooks and curriculum, they accomplished a lot. However, much of the benefits were wiped out by the Soviet invasion of December 1979, the civil wars that followed and the establishment of an authoritarian and fundamentalist Taliban regime.

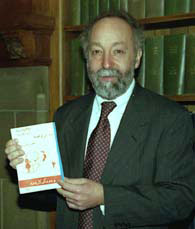

Today, Teachers College is gathering a small working group and contacting a wide variety of American agencies to work out possible plans to resuscitate a new project, but perhaps with new directions, beyond the publication of textbooks. The College is exploring new ways to reach the Afghan people, said Barry Rosen, Executive Director of External Affairs and former Press Attache at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran.

"What strikes me overall is that these books are unlike the Taliban's method of teaching. They sought to institute the ‘madrassah' system which strictly teaches the memorization of the Koran in a highly disciplined fashion and doesn't ask the students to think," said Rosen who can read Dari. "The textbooks created by TC and the Afghanistan Ministry of Education separated religion from the other disciplines and used the Socratic method to encourage thinking."

It is especially interesting to see the science books, he said, because there were no science lessons during the civil wars, the Russian occupation or under the Taliban.

Since the original Afghan Project is fully documented in the archives of the Milbank Memorial Library at TC, said David Ment, Head of Special Collections, UNICEF and other groups that are thinking about their potential in the new situation have contacted the Library recently to use some of the collection.

"These materials provide not just the basis for a new scholarly analysis but also some of the tools that will be needed for the new educational efforts in Afghanistan," he said.

The idea for the Project began after a 1949 UNESCO survey that found the greatest educational need in Afghanistan was teacher training, said Ment. The United States picked that idea up in 1954, and selected Teachers College to do the work, under contract with A.I.D. and its predecessor agencies. Ultimately there were several contracts, with overlapping beginnings and endings, running through about 1978.

During the first few years, the project concentrated on training teachers in the high schools, said Ment. The program was done in conjunction with the Ministry of Education and with teams of Americans and Afghans working together, he added.

Beginning in 1962, the program branched out into a project to develop a Faculty of Education for Kabul University. In 1966, it expanded further with a Curriculum and Textbook project to develop curriculum for all the primary schools of Afghanistan. It was designed to support it with an entire new set of textbooks, as well as teacher training, he said. All subjects-language, social studies, math, science, health, Islamic studies-were included.

"To give you an idea about the size of these projects, I looked at one year where there were 35 Teachers College staff members and about 100 Afghan staff members working on various projects," said Ment. "Ultimately, the Project produced 75 textbooks-in Dari and Pashto-and that was just the tip of the iceberg."

In their first report, the TC team in the Afghan Project said that "the people of Afghanistan must speak for themselves. . . with respect to what they value most, what they want their schools to teach, and what they want their children to become. We have asked some of them, and we have encouraged both teachers and pupils to help us understand what the more important aims of education should be."

The team recognized the need to train Afghan professionals so that they could assume fuller responsibility for educational development. They said, "Our function is to advise. . . Even if we could learn to see, to think, to believe as the Afghans do, we would still insist upon the principle of Afghan responsibility. They are the ones who must live with whatever is developed."

To this end, the project sponsored training of the Afghan professionals at Teachers College and other schools in the United States as well as in programs closer to Afghanistan.

The team showed that they were aware of the difficulties of introducing these modern concepts where the legitimacy of the program and the whole idea of modernization were potentially controversial, said Ment. They were realistic about the challenges of teaching a modern curriculum in the parts of the country with a more feudal setup.

These challenges and others still exist today. A casual observation of life in the refugee camps in Pakistan, especially in Jalalabad, reveals that Afghans still hunger for the textbooks that were published in the pre-Taliban period. This information has come to us through various refugee agencies that have been collecting and using the textbooks from TC's archives.

It's possible that these textbooks could be the foundation for the youth of a new and thriving Afghanistan.

"Much that was done before is still useful. Valuable as these textbooks are, the Afghan Project is far broader," Ment said. "Its usefulness in the future should not be overlooked or underrated."

Published Monday, May. 20, 2002