A Life, Unlimited

Yupha (Sookcharoen) Udomsakdi fled her life in a rural village and became Thailand's Minister of Education and a leading public health advocate

Yupha (Sookcharoen) Udomsakdi fled her life in a rural village and became Thailand’s Minister of Education and a leading public health advocate

By Suzanne Guillette

Yupha Udomsakdi (M.A., ’60) was enrolled in prep school in Thailand, pursuing her dream to study medicine, when World War II broke out. Her mother called her and said, “There’s no need for a woman to become a doctor. Come home.”

Udomsakdi returned to her rural village to help her parents in a family business, but when a friend wrote to tell her about a new nursing school established by American doctors in Bangkok, she didn’t hesitate. She stuffed some jewelry in her pockets and, without telling her parents, set off for the city—and the rest of her life.

Udomsakdi has spent her life ignoring limitations others have sought to place on her. She became the first woman in Parliament to serve in the cabinet, serving on many committees and assisting in multiple rewrites of the Thai constitution; was named the country’s first female Minister of Education; and also founded Thailand’s first health education program. After her retirement from politics, she was elected to serve as a member and the Vice Chairman of the Constitution Drafting Assembly, leading to the creation, in 1997, of Thailand’s most democratic constitution.

Certainly luck played a role in her success—but so did Udomsakdi’s ability to turn adversity to advantage. Girls were rarely allowed to go to school when she was growing up, but because her father was ill, she was sent to stay with her uncle, a civil servant, in the city. One day, her cousin, a teacher, noticed that Udomsakdi was reading well above her second grade level. The cousin took Udomsakdi to school, where she aced her exams, went straight to the fourth grade and won a fellowship.

It was a demanding life. Days began at 5:00 a.m., when Udomsakdi accompanied her aunt to the market. Returning home three hours later, she ate breakfast before arriving at school just in time for the national flag raising. After school, she returned home, did her homework and helped out with chores.

But the experience acclimatized her to hard work, and also put her on a fast track to begin her career. After graduating from the nursing school, she came to New York City, where she studied for six months at a midwifery school on Madison Avenue. She remembers going to her first birth, at the patient’s house: “They looked at me and said, ‘She’s too young!’”

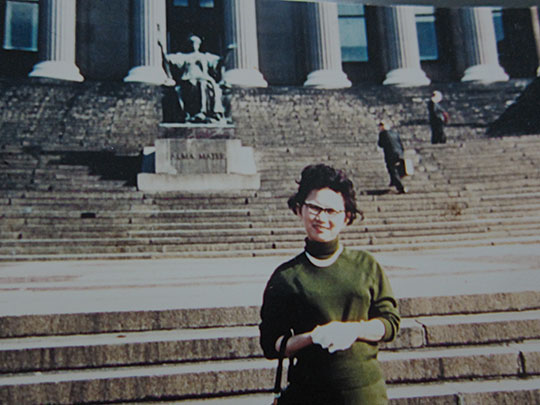

After a Fulbright Scholarship enabled her to earn her Bachelor of Science degree in Nursing Education at Washington Missionary College in Washington D.C., Udomsakdi was accepted to Teachers College, but couldn’t afford the tuition. Fortunately, one of her old colleagues at the midwifery school knew of a foundation that offered funding to international students. Though most scholarship recipients were from Africa, the woman in charge of the foundation granted her $3,500 a year. “I received the check immediately,” Udomsakdi remembers, smiling.

While at TC, Udomsakdi met her husband, a medical doctor and fellow Thai who was a virology research fellow at the Rockefeller Research Center. After marrying at the Thai embassy in Washington, D.C., the couple returned to Thailand, where she began working at a school of public health, Mahidol University. She liked what she was learning, but against the poverty and ignorance in Thai villages, it seemed of little value.

“I approached the Dean and said, ‘No matter how many resources you put into the hospital, it doesn’t matter if, as a people, we don’t know how to look after our own health.’” Out of that conversation came the country’s first bachelor’s degree program in Health Education, employing a “problem-solving process” developed by Udomsakdi in which health workers traveled to villages to “help people help themselves.” Graduates integrated health education into primary and secondary school curricula across Thailand.

The program was such a success that USAID workers filmed the trainings to educate health workers in nearby countries. In 1960, USAID and UNICEF established a training center affiliated with the program that is still thriving today.

Then Udomsakdi hit another roadblock. The World Health Organization, though impressed with the project, questioned whether a nurse should be running it. Again, Udomsakdi turned obstacle to opportunity. Now the mother of two children, she enlisted the support of her family and enrolled at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill to pursue a Ph.D. in higher education administration.

Back in Thailand, Udomsakdi established a faculty of Social Sciences and Humanity at Mahidol to teach social, economic and political education. She also helped establish the first Institute of Population in the country.

With that track record, she finally ran for Parliament. Her decision was prompted by the political unrest in Thailand, which had become a constitutional democracy in 1976. Many of her students were actively fighting for democracy, and when one was shot by a solider, Udomsakdi decided it was time to get involved.

She served four terms, helping to reorganize Thailand’s education system and assisting in four rewrites of the country’s constitution.

After a series of coups d’etat, Udomsakdi decided to step down. She worked briefly as a consultant for UNICEF on women’s and children’s health, and then, at the prompting of a colleague from the Cabinet, entered a new arena: business.

That was 22 years ago. Today Udomsakdi, 82, serves as Chairman of the Board of Chaophaya Terminal International, a company that manages a container port in Songkhla that ships cargo to the Far East, Europe and the United States, and also manages a tourist port in Phuket. She also runs a foundation that funds educational projects in rural Thai villages, and still pays close attention to politics and government affairs. She remains especially proud of the constitution she helped draft in 1997.

“That was the most complete constitution. It was approved by the House of Representatives,” she says, adding with a proud smile, “It had the support of the people.”

Published Friday, May. 20, 2011