Even as statues come down and institutions are renamed, discrimination, harassment and violence against people of color remain stark and pervasive realities. More than 80 percent of all cases in which plaintiffs charge that they have suffered race-based harassment fail — and the vast majority are dismissed before arguments are ever heard.

But that picture may change in the years to come thanks to the publication of two books in 2020 co-authored by TC Professor Emeritus of Psychology & Education Robert T. Carter, who has devoted his career to, in his words, “changing the outcomes, not just the symbols.”

In Measuring the Effects of Racism: Guidelines for the Assessment and Treatment of Race-Based Traumatic Stress Injury (Columbia University Press 2020), Carter and TC alumnus Alex L. Pieterse (Ph.D. ’05), Associate Professor of Educational & Counseling Psychology at the University of Albany, painstakingly establish the damage racism causes to its victims. They build on “empirical evidence accumulated over several decades” to show that “people who are exposed to racism experience stress and have adverse health outcomes such as depression, anxiety and hypertension.”

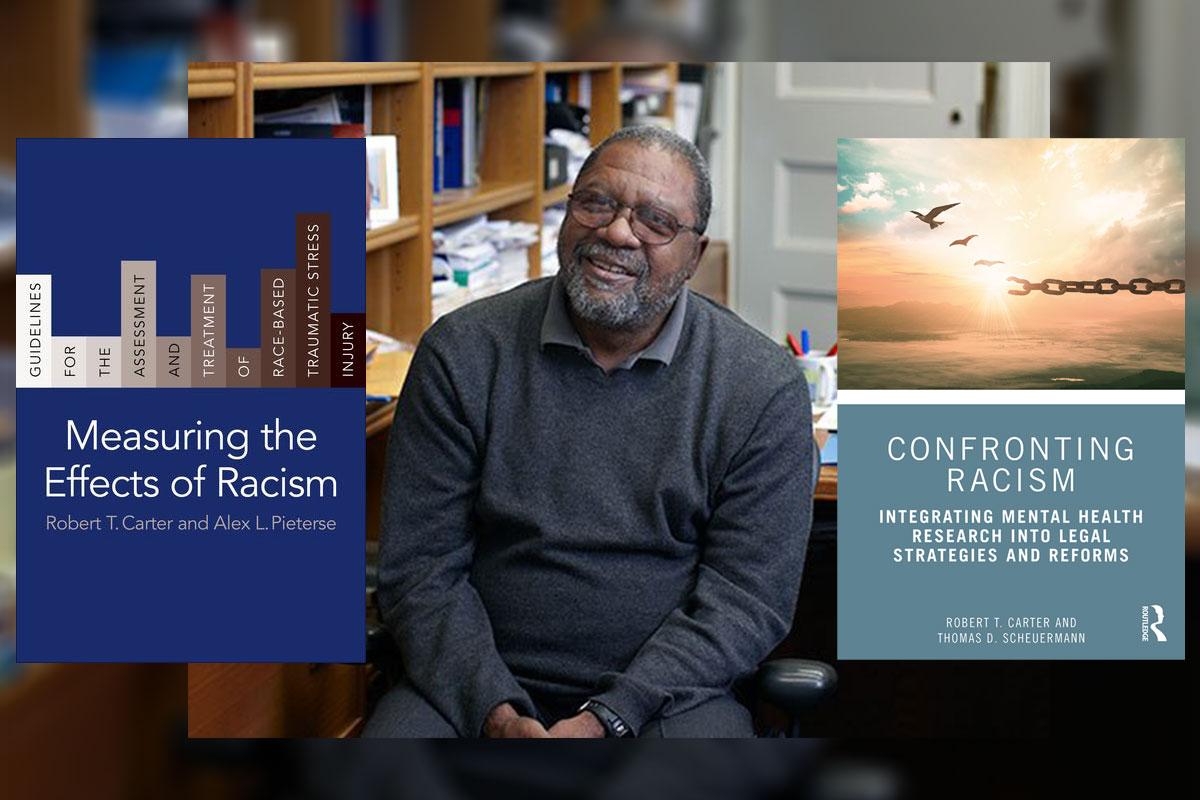

Robert T. Carter

CHANGE LONG IN THE MAKING Professor Emeritus Robert T. Carter's new books distill decades of research and fill a void in the social science and legal literature. (Photo: TC Archives)

In Confronting Racism: Integrating Mental Health Research into Legal Strategies and Reforms (Routledge 2020), Carter and Thomas D. Scheuermann of Oregon State University advance a theory for winning redress for such damages in court, fashioning their approach from tort law — that is, in essence, by redefining race-based traumatic stress as an injury rather than a mental disorder. Using a taxonomy and measurement scale created over many years by Carter and his colleagues, plaintiffs could, in theory, draw a direct line to a specific event and argue that they have suffered quantifiable harms because of it.

“For the most part, our history is characterized by decisions about race and racism being made to promote the interest of Whites,” write Carter and Scheuermann. “The social science and legal professions, each and together, can be seen, based on their paucity of meaningful action, as reluctant to actually address how injurious racism may be to individuals and groups, as well as to our broader society.”

It is too soon to judge where the protests generated by the killings of George Floyd and other innocent Black people will lead. But some day, the publication of Carter’s books may well stand as the starting point for outcomes that go beyond symbolic change.