As my school returned to the physical classroom for the first time since the pandemic began, I wanted students to experience our classroom space in a new way. I hoped the space would foster collective learning that happened organically versus as a pre-determined goal. As the Wandering Curriculum suggests, materials change an experience. Materials foster creativity and imagination by placing objects and artifacts in our presence so that we have something to react to. My hope was to curate a space where that reaction would turn into connections made with oneself, others, and the curated materials.

My mind instantly wandered back to a book I read and wrote about during my time at TC called Wired to Create. The authors asserted that at the core of our existence, humans were wired for interpersonal relationships and driven to create. A challenge was that the pandemic made an innate connection with others seem impossible in the context of virtual classrooms. Nevertheless, Wired to Create embraced getting to know our inner selves through sensory and spatial experiences. The book uncovered the tangled complexity of the creative human brain with the purpose of inspiring readers to unlock their creative potential, and in the process, attain a deeper sense of themselves and the world around them. This brought me to the provocation Andrea and I did on the first of weekly meeting prompts.

Returning to a reading from last semester, “Walking-with place through geological forces and land-centered knowledge” by Stephanie Springgay and Sarah Truman, I thought connecting us to diverse sets of knowledge other humans possess could happen through exploring materialities of place in the classroom. The reading included sentiments from feminist geographer Doreen Massey (2005) who has been a highly influential scholar in re-conceptualizing space and place as socially constructed, relational processes. Space, writes Massey (2005), is contingent and in flux, “the product of interrelations,” and is “always under construction” (p. 9). Place, as such, is conceived of as a process. The idea of place and space as separate distinctions for Tim Ingold (2000 ) is fraught with problems. People, he argues, do not live in a place, but move through, around, and between them, such that places are more akin to knots “and the threads from which they are tied are lines of wayfaring” (p. 33). Wayfaring is less a path from point A to B, and more of a meshwork of lines and movement, “a trail along which life is lived” ( Ingold, 2011 , p. 69). If space is open and place cannot be assigned a prior location, then we need different ways to articulate place-making.

In our provocation for Curriculum Lab, Andrea and I proposed an exploration of the materialities of place in our developing curriculums through these questions:

- Where are we? What materials are around me?

- How do I read the materiality around me?

- How can the places we are in inform the curriculum we are developing?

During our breakout room session, a conversation centered around curation of space developed. I had initially asked my breakout room to describe the surroundings they were in. Yvonne was in her son’s room, where there were African American male icons on the wall such as Dr. Cornell West, Thelonious Monk, and Fredrick Douglas, African American pilots from WW2, a Black astronaut, notes from her father and notes that he sent to his grandson, along with pictures of his friends and childhood memories, and Haitian paintings. All these were there to purposely create a space filled with powerful, intelligent, black men who experienced adversity but still shared their brilliance with the world. Even the colors of Haitaian blues were used to create a space of calm and peace since moving from the home in which her son was raised, to a condominium, was a change. Our group discussed the significance of creating safe, inspiring, anti-oppressive spaces for students in a time of sanitized history and considered Fugitive Pedagogy as a historical example of why the work we are doing here is necessary.

Bringing this into my personal, professional practice

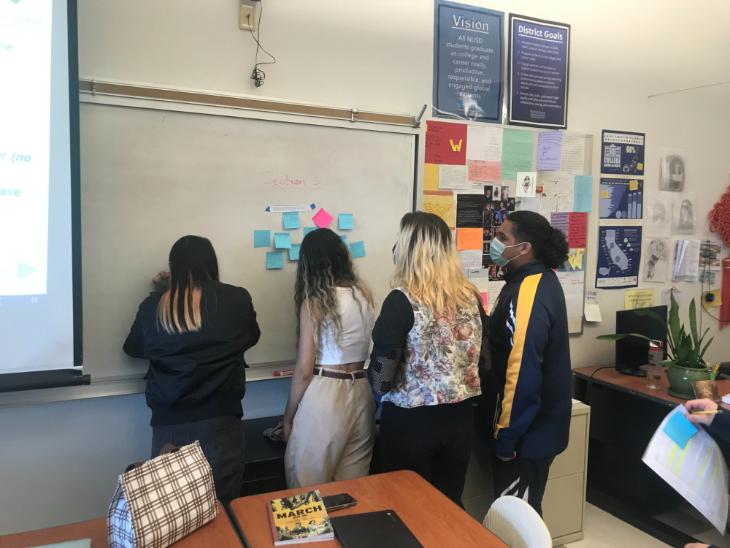

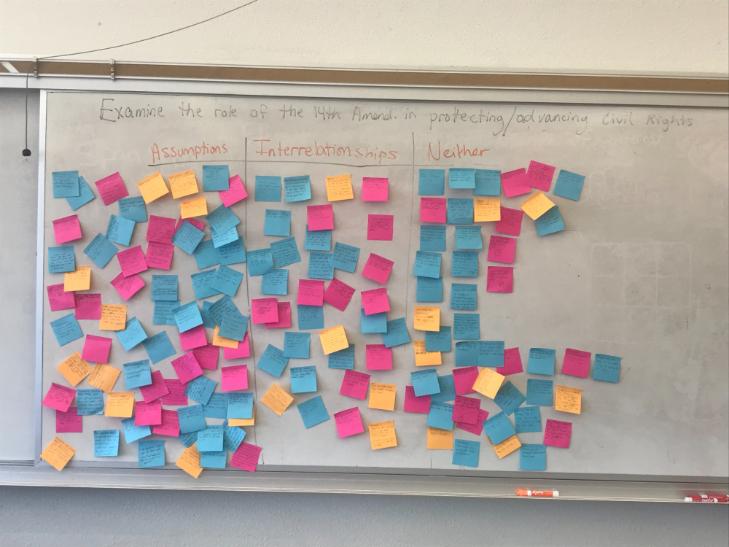

Taking these theoretical underpinnings as well as qualities and generative strategies from the Wandering Curriculum into consideration, I curated a thought museum (modified from the strategy used by Facing history and Ourselves) for students to engage with. The tangled complexity of the creative human brain would unravel and create a meshwork, in the form of thoughts, on post-its.

Thought Museum

Day 1: In this modified activity from Facing History and Ourselves, I posted 8 quotations around the classroom; each quote was considered an “exhibit.” Then students took several sticky notes, wandered around the room, and added comments or questions that arose for them, or a connection between the quote and another historical event, current event, or personal experience. 8 volunteers then acted as “curators” and facilitated a discussion based on the synthesis of thoughts on the post-its. As the discussion unfolded, the class was able to uncover some assumptions and interrelationships of the 14th Amendment and the quotations provided. This was our content focus for the topic of Reconstruction. Finally, we dissected an IB exam prompt by organizing the meshwork of post-its into categories of “assumptions,” “interrelationships”, or “neither.” This served as an informal literacy objective.

Day 2: The culminating activity was a 30 min essay write. Students chose post-it comments they thought would help them answer the prompt and used their annotated 14th Amendment paper from the beginning of this learning segment to answer the prompt. After the 30min I had students peer grade each other's papers using the IB Paper 3 mark scheme (rubric). They text coded papers to identify where in the papers students met the criteria of the mark scheme, and then gave a 3 sentence summary of why they gave them the grade.

Since materials and objects provoke emotions, memories, and different bodily sensations in our stories and experiences, I found our classroom and the materials produced in it a space to gather our diverse sets of knowledge and apply them. To an extent I needed to follow a framework set by the International Baccalaureate program, but had agency on executing approaches to teaching and learning for our topic of study. I didn’t get to unpack all of the learning that was generated from this wandering exercise, but learning in itself felt enough. As my work shifts to creating an Ethnic Studies course for our district and implementing it as a pilot at my high school site next school year I will center on these questions within the context of redefining literacy and how literacy is shaped:

- Consider hybrid identities and how they may shift across time, space, and situation. What is/are your social location(s)?

- How are the spaces you traverse racialized, classed and gendered? How is power and privilege working in those spaces?

With my primary goal to foster collective learning, it is our responsibility as educators to create safe, anti-oppressive spaces for students (Kumashiro, 2000). This is an important skill in understanding history and connecting history to one’s own lived experience and the real world versus the sanitized history presented in curricula. As such, an implication can be made where understanding history is a process of uncovering meshwork; the tangled complexity of diverse sets of knowledge, past and present.