Lunching With A Legend

One reason students come to Teachers College is the impressive number of historical figures in education who once walked these very halls.

One reason students come to Teachers College is the impressive number of historical figures in education who once walked these very halls.

Some of those figures still do- and on occasion, they walk right into the classroom to discuss their work.

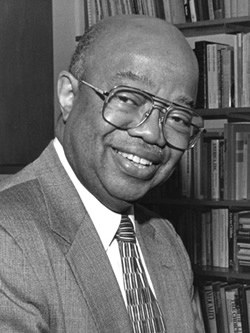

Such was the case in December, when the Petrie Fellows- a group of TC students who are receiving full scholarships in exchange for a commitment to teach in New York City schools for at least five years after graduation- enjoyed lunch and a private chat with TC Trustee Dr. James Comer. Comer, the Maurice Falk Professor of Child Psychiatry at Yale University and Associate Dean of the Yale School of Medicine, is the legendary creator of the Comer School Development Program, which brings together parents, educators and the community to improve children's lives in and out of school. The Comer program has been implemented at nearly 1,000 schools across the country.

"I don't have many heroes, but he's one of them," said TC President Arthur Levine in introducing Comer, who has authored several highly influential books- including Leave No Child Behind: Preparing Today's Youth for Tomorrow's World- and received honorary degrees from more than 40 different colleges and universities.

If numbers are gold in the currency of today's education climate, the Comer method is rich in results. Launched in 1968, the program took the first two schools it was introduced in "from 32nd and 33rd to the district's third and fourth highest levels of achievement and best attendance with no serious behavior problems," Comer told the group.

The program is still going strong today: Introduced in a school district in North Carolina five years ago, it has boosted schools with only 42 percent of students at state proficiency levels all the way up to 98 percent of proficiency. In fact, among the 29 model school reform programs that have gathered sufficient outcomes data for comparative assessment, Comer's is one of only three that has been shown to improve test scores on a broad scale. Just as importantly, the program is credited with introducing methodology that is now standard among school reform efforts, including field-testing its tenets prior to dissemination and then rigorously evaluating their effectiveness on an ongoing basis.

Yet Comer's message to the Petrie Fellows was the same that he has delivered to educators for the past 30 years: numbers are only part of the story.

"I'm concerned that so many people in education- superintendents, school boards, principals, teachers now, policy makers- are focused on test scores alone," he said. "That's not what the schools are for, nor is it as important as other aspects of child growth and development. We should be preparing children to be successful people and to be successful family members, successful citizens- and particularly in early elementary school, before they are eight, nine, 10, 12 years of age."

Developed at the Yale Child Study Center, the Comer program seeks first and foremost to ensure that all adults affiliated with a school are working in sync and focused on the welfare of students. For that to happen, schools must deal with the early developmental experiences- or lack of them- that often produce troubled children who can disrupt even the best-run classrooms.

"Many children, particularly from poor and marginalized families, come to school underdeveloped in the areas necessary to be academically successful," Comer said. "And most of the teachers and the administrators have not had the preparation in child development and support that will allow them to help those children grow in those areas so that they can then be successful. That can create a chaotic environment where the adults are just fighting for survival. Instead, all of the adults need to think of their jobs as being about helping children grow rather than being about the control and punishment of the children."

Comer's system creates three teams within a given school. The School Planning and Management Team, headed by the principal and made up of teachers, administrators, parents, support staff and a child development specialist, sets targets for social and academic improvement, establishes policy guidelines, develops school plans, addresses problems and keeps tabs on program activities. The Mental Health Team, also headed by the principal and staffed by teachers, administrators, psychologists, social workers and nurses, analyzes social and behavioral patterns within the school and determines how to solve recurring problems. The Parents' Group involves parents in all levels of school activity, from volunteering in the classroom to school governance.

Guided by the program's three core operating principles- consensus, collaboration and "no fault" (a taboo on assigning blame), a school's adults "actually get a chance to like each other- and when people like each other, good things happen as they work together," Comer said.

During a question-and-answer session at the end of the lunch, one student raised her hand and asked, "Dr. Comer, all of this sounds so impressive- but if grades and test results aren't the most important thing, how do you know when your program is really beginning to work?"

Comer smiled. "I remember at our school in New Haven, we had a nine-year-old from a difficult family situation who'd come to us after three transfers the semester before. His first day with us, someone stepped on his foot during an exercise, and right away, he's ready with his fists. And then another kid said, "Hey- we don't do that in this school." And the new boy looked around at all the other children, and their faces told him it was true. And that was it. The fists went down. And we knew we were doing something right."

Published Thursday, Feb. 23, 2006