Celebrating Rosalea Schonbar

By Elizabeth Dwoskin

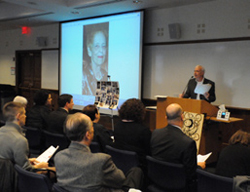

‘What was primarily purple, tie-dyed, loved whales and smoked?,’ Dr. Barry Farber asked a group of about 40 people gathered in 179 Grace Dodge Hall on a Saturday morning in November.

Farber, the director of the Clinical Psychology doctoral program, wasn’t telling a joke, but everyone in the room knew the punch line: Rosalea Schonbar.

That morning, family members, colleagues and former students had come to pay tribute to Schonbar, a professor emerita and former director of TC’s clinical psychology doctoral program, who died in July at the age of 90.

Schonbar, who retired in 1990 after 50 years on TC’s faculty, was among the first women in the country to direct a clinical psychology program at the doctoral level. She also served as President of New York State Psychology Association in 1977 and 1978 and again was one of the first women to hold the title.

Schonbar began as a practitioner of the Rogerian method, which emphasizes the therapist’s ability to be empathic, genuine and positively regarding toward the patient. Later, she adopted a more depth-oriented psychoanalytic technique, one that also emphasized the relationship between patient and therapist, said Farber.

Schonbar was first hired by TC, as an associate in the Guidance Laboratory, in 1949. Even after retirement, she continued to supervise student dissertations and teach courses. She published articles on dreams, on fees in psychotherapy, on professional ethics and on psychoanalysis—including a well-known essay on Freud’s famous case of “Anna O,” co-authored with a former student, Helena Beatus.

The diverse group of students, colleagues, faculty and family who came to the memorial service organized by Farber and Ellen Kelliher, Schonbar’s niece, were a testament both to Schonbar’s influence and her personal charm. In attendance were students she had trained from as far back as the 1960s, a former housekeeper (Schonbar had counseled her through a divorce); and not one but three home health aids who had nursed her in her Upper West Side apartment in the years before her death.

“She was a very centered person,” said Christie Virtue, a ’91 graduate who directs an early childhood intervention program in Harlem. “And a centered person helps you be more centered. You learned from how she modeled being a therapeutic presence for you.”

“She was just a very direct, no bullshit sort of person,” said Anthony Bass, ’83, a faculty member at both NYU and Columbia who serves as joint editor in chief of Psychoanalytic Dialogues, and co-founded the International Association for Relational Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy. “There was just a sense of her as absolutely who she was.”

Though Schonbar was clearly an intellectual leader, people also described her as understated and down-to-earth—someone who was as comfortable watching a Mets game on the couch with her nephew as she was lecturing on dreams and the unconscious (which she did on cruise ships to the Caribbean as well as at TC). Schonbar was an avid amateur photographer, loved ships, invited her students to the opera and hung out with them on Cape Cod, where she photographed whales and shared cigarettes with them in her TC office. She was also known to favor fashionable pants suits and to tie-dye her own socks. She loved purple.

“In my job interview,” Farber recalled. “We discussed the Knicks, the Mets and appropriate places to put commas in academic journal articles.” Another student said he and Schonbar spent the 50 minutes of his interview with for the doctoral program discussing the painter Cezanne. Another remembered talking about the photographs on the walls of Schonbar’s office, a place that, long after smoking was banned in the halls of TC, served as the school’s informal smoking lounge.

Indeed, to honor Schonbar’s notorious habit, the memorial service programs were rolled up like cigarettes and placed in boxes designed to look like oversized packs of Kent’s. More substantively, Schonbar’s family and Farber had also created the Rosalea A. Schonbar Scholarship Fund at Teachers College.

“Rosalea was cool, you know?,” said Richard Eichler, the director of Counseling and Psychological Services at Columbia. “She took a quiet satisfaction in other people’s accomplishments. There was a certain subtlety about her. You weren’t always aware of how much, from talking with her, you were able to clarify your own thinking.”

“She loved TC, every single thing about it,” said Kelliher. “Her colleagues, students—these were her family.”

In a group of psychologists, naturally, there were tinges of psychological training in everyone’s remarks. “Her stylish home—with all its objects—was like a manifestation of the unconscious, but also womblike,” a former student recalled.

That quality seemed an extension of the woman herself.

“She was like a mom waving at you from the end of the hallway,” said another former student, in a video clip from her 1990 retirement party that was shown at the service. “It made you feel solid, secure, like you could go out and tackle the world.”

Published Monday, Dec. 20, 2010