With the Syrian government inflicting atrocities on its own population, the United States and North Korea threatening each other with nuclear attack, and dictators seemingly on the rise worldwide, the United Nations’ recently re-energized attempt to reorganize itself around the goal of sustaining peace may seem an empty gesture. Yet a recent UN declaration to that effect, together with twin UN resolutions and a major report just released by UN Secretary General António Guterres, reflects a slow but growing movement in the international community over the past 25 years aimed at shifting global emphasis toward sustaining peace and away from the traditional approaches of crisis management and mitigating war.

SUSTAINED EFFORT Coleman a (third from right), Fry (sixth from right) and colleagues presenting at a recent International Peace Institute forum.

That movement is now being informed in significant part by the Sustaining Peace Project, a multi-year Manhattan Project-like effort led by Teachers College psychologist Peter T. Coleman, Director of the Morton Deutsch International Center for Cooperation & Conflict Resolution. Coleman, Professor of Psychology & Education in TC's Department of Organization & Leadership, has assembled a multidisciplinary A-team of internationally known researchers to create a working model of the dynamics that promote and sustain peaceful societies.

“The international community doesn’t know much about sustaining peaceful societies, because those societies are rarely studied,” Coleman says. “Instead the focus is usually on the study of peace processes in the context of war, whether conflict is just breaking out, escalating or stalemated. That’s like studying bankruptcies to understand how to foster thriving businesses. Genuinely peaceful societies are wholly different animals from those rebuilding after war.”

[ Read “Sustainable Peace,” by Coleman and colleagues. ]

In his own research, often working with the social psychologists Robin Vallacher and Andrzej Nowak and the astrophysicist Larry Liebovitch, Coleman uses a complexity science approach from applied mathematics, called dynamical systems theory, to identify “attractors” – strong patterns, caused by complex interactions between many different factors, which resist change and create persisting dynamics. For decades, Coleman’s team studied more intractable conflicts as attractors, like those seen in Israel-Palestine. More recently, he has turned his attention to the study of sustainably peaceful societies through a similar lens, drawing on psychology, complexity science, peace and conflict studies, and various other disciplines to develop a basic and holistic understanding of sustainably peaceful societies.

“The international community doesn’t know much about sustaining peaceful societies. Instead the focus is usually on the study of peace processes in the context of war, whether conflict is just breaking out, escalating or stalemated. That’s like studying bankruptcies to understand how to foster thriving businesses. Genuinely peaceful societies are wholly different animals from those rebuilding after war.”

Another key member of the project is the anthropologist Douglas Fry of the University of Alabama-Birmingham, whose pioneering research has led the way in conclusively demonstrating that there are, in fact, scores of fundamentally peaceful societies. In work such as his landmark 2012 study, “Life Without War,” which compared three inter-societal peace systems – the Upper Xingu River basin tribes of Brazil, the Iroquois Confederacy of upper New York State, and the European Union – Fry has begun to provide an evidence base of the basic societal conditions that sustain peace. Fry builds his case on archeological evidence that has shown that war is a relatively recent phenomenon, emerging during the past 10,000 years as humans began settling and claiming territory – a finding that refutes the notion that people are inherently warlike. His research suggests that societies are much more likely to evolve in peaceful directions if they have a clearly specified sense of what this entails, and that when societies define themselves as peaceful, they are much more likely to act and organize themselves in a consistent manner.

Other project members include Liebovitch, a faculty member at Queens College (CUNY), who is “mathematizing” the team’s model to capture interactions among hundreds of variables that contribute to attractors for sustainable peace; and researchers at Columbia University Earth Institute’s Advanced Consortium on Cooperation, Conflict, and Complexity (AC4), including scientist and project coordinator Jaclyn Donahue. More than 75 other scientists worldwide have contributed ideas about research relevant to the project, and Coleman’s group is also field-testing its work in real-world settings such as Spain’s Basque region, where peace has held for the past several years following a half-century of civil war.

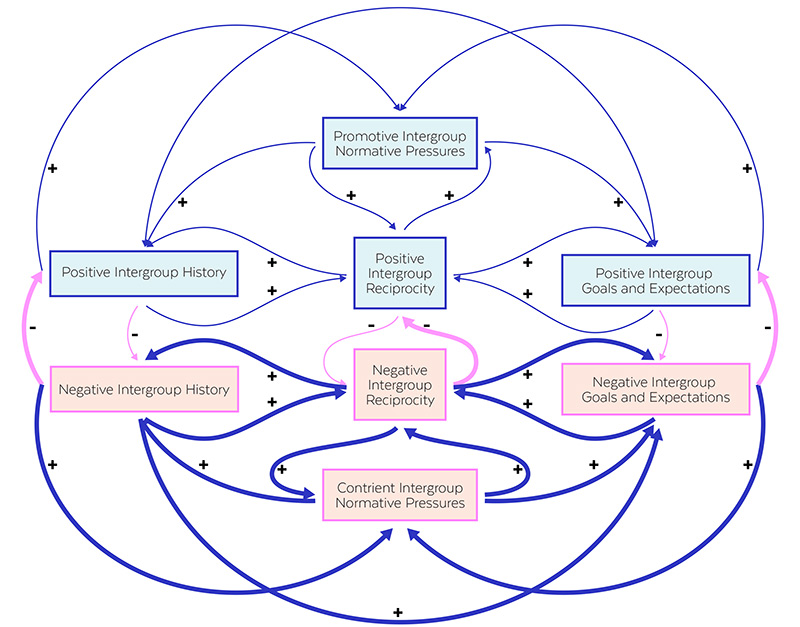

“HIGHLY COMPLEX BUT FUNDAMENTALLY SIMPLE” A complexity map of the core dynamics of sustainably peaceful societies from the Sustainable Peace Project. Coleman's group believes that peacefulness in communities is, at its core, a function of how members of different groups treat one another.

The ultimate result, the group hopes, will be an enhanced understanding and visual map of the dynamics of sustainably peaceful societies, as well as an interactive website tool (what Liebovitch calls games) based on the mathematical model, for use by policymakers, negotiators and others to help build and sustain peace.

Slow Build

There have been four phases to the Sustainable Peace Project in the three years since it began. First, the group reviewed and synthesized research from Fry’s case studies of peaceful societies, surveyed 75 scholars from 35 different disciplines and mined other published research as well, in order to identify the core dynamics involved in sustainably peaceful societies. Using that information, they created a “causal-loop” diagram to visualize how different variables in an enduringly peaceful community interact with one another over time to establish strong attractors for peace. The diagram also reflects secondary and even third-level dynamics set in motion by these relationships.

“Obviously we have privileged academic research thus far, so it’s really important that we don’t just sit in our offices and make this stuff up. Communities struggling to make and sustain peace are not shy about telling us what is useful and what is not.”

Second, in order to determine if their model has real-world relevance, the researchers are re-coding Fry’s ethnographic database of peaceful and non-peaceful societies to see if their model correctly predicts these differences. A group of students led by Donohue is also mining the published empirical literature to better understand how, over time, certain kinds of positive or negative interactions within societies morph into a sense of cultural norms and practices that shape people’s understanding of the past and hopes or fears about the future. Their efforts are patterned after work by the psychologist and mathematician John Gottman, whose predictive model for thriving versus divorced couples focuses on their ratios of positive interactions to negative ones.

“Peace is highly complex but fundamentally simple,” Coleman and his team have written. “Although a large array of factors can influence peacefulness in communities, at its core it is quite simply a function of how members of different groups (national, political, ethnic, and so on) mutually treat one another. In other words, the higher the ratio and strength of acts of reciprocal kindness, respect, inclusion, and so on, to acts of hate, contempt, exclusion, etc., the higher the probability of sustaining peace.”

Third, Liebovitch has created an algorithm that captures the interactions between all of the variables the team has identified as being essential to sustaining peace and is testing it to see if those factors behave with corresponding power in a mathematical relationship. This model has resulted in a computer simulation that the team plans to develop into a “game” for policymakers and community leaders to build peace.

And finally, in the Basque region, Afghanistan and elsewhere, Coleman’s team has been asking community stakeholders what they believe are the key determinants of lasting peace and trying to determine whether the project’s model can be of use to them.

“Obviously we have privileged academic research thus far, so it’s really important that we don’t just sit in our offices and make this stuff up,” Coleman says. “Communities struggling to make and sustain peace are not shy about telling us what is useful and what is not.”

Broader Context

Coleman is to some degree heartened by the recent UN Secretary General’s Report, which details gains made in moving toward an international focus on sustaining peace. But in a critique titled “Half the Peace,” just published in Global Observatory, the web publication of the International Peace Institute, he frames several major hurdles that are hampering that effort. Among them are Hobbesian assumptions driving much of the thinking on international affairs about the selfish and violent nature of human groups, and the tendency among scientists and policymakers to focus more on the prevention of what humans fear rather than on opportunities to maximize what they most hope for. Coleman also cites the general orientation of the UN to work slowly and with extreme caution for fear of angering UN Member States, as well as the tendency of the international community to approach the world’s increasing complexity with thinking that is “systems light,” ignoring the full complexity and volatility of factors that contribute to sustainable peace. Still another obstacle, he says, are those who champion a distorted notion of peace-building that reflects capitalist economic goals – a pointed reference to the Austrian billionaire Steve Killilea, whose Institute for Economics and Peace has created a Positive Peace Index that Coleman believes is fundamentally limited by a strong pro-business agenda.

“Their current peace index lists Israel, Qatar, Hungary and Poland as being among the top positively peaceful societies,” he says. “It really depends on the lens you apply – and capitalism is not always good for peace.”

Still, he remains hopeful overall. Or as he and his colleagues recently highlighted in quoting the noted economist Kenneth Boulding, “Anything that exists is possible.” The scientific evidence suggests that living in peace is both possible and replicable.” – Joe Levine