WELCOME TO OUR A.I. DECISION-MAKING CALCULATORS

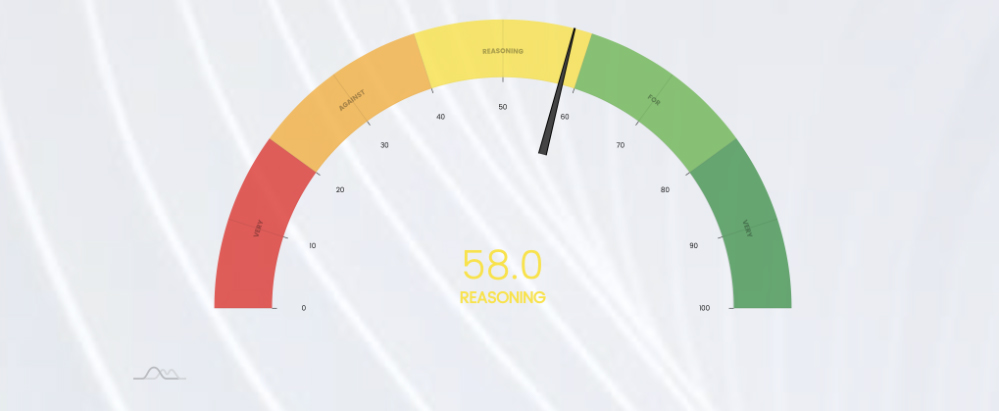

Our short and extended calculators aim to help you seriously think through an important personal decision with input and insights from A.I. You can select which calculator below on this page. They provide a new way to summarize how your own reasoning stacks up overall with a single score using our pro, con, counter reasoning analysis. The dial below illustrates the 100-point scale, which is based on your pro and con reasoning plus your own counterarguments. Using A.I. alone without recent scientific advances often misses important questions, which our calculators aim to include. A.I. can also inadvertently bias decisions when a person sees A.I.'s summaries without rating their own reasoning.

However, we also harness the power of A.I. to inform you about factors you may not have considered, thereby potentially improving your decision making. Our calculator survey process with A.I. inside aims to help advise your decision (but not dictate it). We focus on one decision option at a time ("go/no go"), which is common for many important life decisions (e.g., accepting a job, going to an event, staying in a relationship) . See FAQ below if you have to compare multiple options, such as assessing one at a time or using a decision matrix.

Simple steps

- Chat with A.I. and get its input.

- Analyze your pro and con reasoning.

- Examine your counterarguments to go deeper.

- See your overall reasoning score calculated from all of your inputs. Then, evaluate your confidence and satisfaction to see if you need even more information.

Helpful tips inside

The calculators provide helpful decision tips as you proceed. The extended version provides relatively more.

Shortened A.I. Decision Calculator

You chat with A.I. right away and analyze your reasoning afterward. Try to have at least 5 to 10 min available. More complex decisions may take a little more.

Extended A.I. Decision Calculator

You analyze your reasoning before and after A.I. See how it changes. Many Tips are provided. Try to have at least 15-20 minutes available. You can take breaks.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the purpose of these A.I. decision-making calculators?

The A.I. Decision-Making Calculators, created in the Dynamic Network Lab, aim to help you, your team, or a group you represent carefully think through important subjective decisions in an effort to promote your decision clarity, confidence, satisfaction, and reduce regret. To do this, the calculators assess your specific reasoning and counterarguments. The science of the A.I. Decision-Making Calculators is grounded in behavioral reasoning theory (e.g., Professor James D. Westaby’s theorizing and methodologies), deliberate reasoning processes (e.g., aspects from Kahneman and Tversky's work), and other critical concepts from many leading theorists in the social, organizational, and decision sciences. We refer to it as Pro, Con, Counter Reasoning Analysis (or PCCR analysis or Triple Reasoning Analysis).

Who's the audience?

Anyone can use the calculators (18 or over), but they are most relevant to people that are serious about carefully analyzing their personal decisions. A limitation of many overly simple decision approaches (e.g., a simple listing of pros and cons only) is that they ask an insufficient number of questions or do not allow participants to rate their reasons or beliefs, nor do they often combine them systematically, based on recent validated theory. Our approach does this, especially because our results indicate that such ratings greatly improve the predictions of decisions and satisfaction, scientifically speaking.

How do I start?

It’s simple. You can get started immediately by clicking on either the shortened or extended version. No registration is required. No names and no emails are needed. This is to promote anonymity so you can feel comfortable sharing your honest thoughts without feeling judged.

Is it private?

Yes, the calculators are private and confidential. We do not request participants’ names, and we do not connect identifying information to individual responses in efforts to keep responses anonymous.

Is it voluntary?

Yes, participation is fully voluntary. You can stop participating at any time. The informed consent page inside the calculator provides more details.

Is there a cost or advertising?

There is no cost and no advertising in the calculator.

What kind of decision can I examine in the calculator?

It can be any kind of important personal or professional decision that you are thinking about that needs a serious analysis. Thousands of people have used our earlier calculators to examine a wide variety of decisions, such as to stay in my job, keep my relationship, purchase an item, school choice, seek professional help, relocate to a new city, etc. Although the calculators cannot guarantee outcomes, accuracy, effectiveness, or satisfaction in decisions (nor can it monitor or confirm the accuracy of any stimuli presented by A.I.), they aim to help provide a much deeper than normal analysis. Importantly, if your decision is related to any serious personal, health, or psychological well-being issue, please seek professional help since the calculator nor A.I. is a replacement for those situations, such as calling 911 for an emergency or 988 for crisis counseling. Other good sources for psychological or decision-making information include the American Psychological Association Help Center: http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/index.aspx).

What if I have multiple options? I know the calculator focuses on single decisions

If you have more than one option, you can repeat a calculator on the different options and compare scores. We recommend starting with the option you have thought about the most. If it's clearly rejected, you can move to the next option and collect more information as needed. A very important use of A.I. before even visiting our calculator is to seek various options related to a given decision context early in the process. Our calculator becomes most important when you become focused on the acceptability of a single option and how it may relate to your fuller life context (e.g., should I buy this options or not?). A.I. tends to not be well equipped to ask (and scale) the most relevant questions, based on most recently validated psychological theory..

Or, you can use "multi-attribute decision making" and decision matrix approaches on multiple options, which are easy to find with A.I. or search online, but require you to rate all options on exactly the same attributes/reasons. However, this may not reflect the reasons you normally think about for each option separately, based on our research (e.g., you may generate different reasons/attributes for different options, while decisions matrices require the same attributes for all options). There are advantages and disadvantages to each approach. We encourage future research to compare approaches, including research from the Keeney and Raiffa tradition.

Are there shorter versions I can use without a computer or A.I.? Or a simpler bot?

Yes, beyond the shortened version on this page, please check back here in the near future for some downloadable versions that you can use with paper and pencil, on flip charts, or in word processors. This can be especially helpful when discussing a decision in a group or if one does not want to go through the steps in the calculator. New bot versions of the calculator are also in development in the Dynamic Network Lab. We anticipate that these (or commercialized ones) will become more popular over time to simplify discussions, especially in coaching, counseling, or advising contexts, but it may come with risks if not enough critical questions are asked by A.I. -infused robots, not to mention the ethical issues that arise when a for-profit company is generating bots and the information they are displaying and managing. Our calculators here are for research purposes only.

How does the reasoning assessment work?

In Westaby's Pro, Con, Counter Reasoning Analysis, the calculators automatically combine your own primary pro and con reasoning, your counterarguments, and your comparative reasoning into a summary score. The process is aimed to help you make a more informed, deliberate, and justifiable decision, now integrating insight from A.I. as well. We recommend that those engaging with the calculators be as knowledgeable as possible about the issues (and options) related to the decision, since research suggests that this may help reduce decision biases (See last bullet in the FAQ for a partial listing). The A.I. interface is also aimed to provide you with more information for your decisions. While the calculator cannot guarantee positive outcomes of your decision-making, it may help you more deeply process and understand the important issues, arguments, and situations you face today and to anticipate in the future once your decision is implemented. Your participation also provides key input into research that aims to advance decision quality and satisfaction. In turn, this may help researchers improve the calculators in future iterations or decision discussion in advance bots that interfere with people daily about their lives.

Where did it come from? Who does this research?

This research is conducted by university researchers in the Dynamic Network Lab, Program in Social-Organizational Psychology, TC, Columbia University. The primary investigator is Professor James D. Westaby. Please visit the Lab for a full listing of collaborators.

What is the analysis? What are some key scientific papers?

The calculators are scientifically grounded, based on what we refer to as Pro, Con, Counter Reasoning Analysis. This coined analysis from our Lab is based on multifaceted behavioral reasoning theory, extending the original behavioral reasoning theory (James D. Westaby & colleagues, 2005-2025). We also refer to it as Triple Reasoning Analysis or PCCR Analysis for short. General A.I. platforms often miss many variables related to the science of decision making and the prediction of human behavior when they try to provide summarized answers. We try to assess many of these factors and provide an overall score based on scientific findings, which A.I. normally has difficulty doing, given that it tries to generalize across web data and often refrains from telling individuals what to do, given its often self-imposed guardrails.

Key references:

-

- Westaby, J.D., Rosemarino, N.M., & Elliot, A.J. (2025). How Behavioral Reasoning May Further Explain the Belief-to-Behavior Connection: Exploring the Role of Primary Reasons, Counter Reasons, and Comparative Reasoning Facets. Psychological Inquiry, 36 (1), 67-74.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2025.2482353 (Open access/free download)

-

- Westaby, J. D. (2005). Behavioral Reasoning Theory: Identifying New Linkages Underlying Intentions and Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 98, 97-120. (The paper introducing the original BRT theory).

What is the scientific evidence for the calculator?

Preliminary results on a diverse U.S. sample show predictive validity of the calculators' reasoning concepts on reliable scales across important human decisions, such as those related to relocating, job decisions, purchases, family decisions, and relationship decisions. Moreover, users have demonstrated statistically significant increases in average satisfaction after completing the calculator. Although the calculator cannot guarantee increases in every case, initial results demonstrate positive decision outcomes on average. Research continues to test the approach, and we encourage the field of decision and psychological science to compare the pro, con, counter reasoning approach in the calculators to others, such as those based on subjective expected utility theory.

What's different from using just general A.I.?

Here, your own personal reasons and counterarguments are carefully measured and scaled. Asking A.I. alone about a decision will often have it find an average set of pros and cons from the universe of web data across all people but not integrate your own reasoning, arguments, and validated scales that predict decisions and satisfaction. That usually requires a selected theoretical framework, which we provide based on very recent validated scientific evidence.

What does general A.I. do when people ask it to decide for them?

Mainstream A.I. platforms typically avoid a direct response. It tends to not automatically provide people an overall quantitative summary for their personal decisions on a 100-point scale, based on a recently validated theory. Although one can try to prompt it, the results are rarely consistent depending on the algorithms it applies quickly. It often has such reluctance because (1) it would see that various psychological approaches exist that provide different algorithms to gauge implied rational choice and cannot determine the best one in all cases and will not typically engage in meta-analyses to advise that selection, (2) general A.I. often does not engage in data collection about people's own reasoning, which typically also requires psychological models to inform the questions, and (3) A.I. often has self-imposed guardrails based on the developers that limit its directives (e.g., “I cannot make the decision for you, as the best choice depends on your specific lifestyle, living situation, and preferences.” (Google Gemini Quote, 2025). However, A.I. may be an incredible tool to inform the decision process, which we integrate into our calculators for your subjective decision making. Also, for cases where an objectively correct answer is possible, one can simply ask an A.I. for a clear answer (e.g., "Is taking highway A the shortest route to location B?" - a clear answer would be provided, because there would be little error variance in its estimate based on well-agreed-upon mathematical formula). We hope our calculators will start to inform how researchers and A.I. platforms can develop bots that can balance this subjective-objective divide along with the addressing ethical issues associated with personal data collection from commercialized A.I. businesses. Our calculators are research-based, IRB approved with an anonymous design, and not commercialized. Our goal is to better learn how people make decisions they feel committed to and satisfied with over time for their well-being with technological assistance. We hope this can then inform new developments in user-friendly bots that also potentially address the tradeoff between "I want to very easily make this decision" and "I want to make sure I've carefully thought through all the important factors so I don't make a mistake and minimize future regrets". This is related to important conceptualizing about effort/accuracy tradeoffs in decision science (Payne, Bettman, & Johnson) and why we have two different versions at this time, although we hope research will indicate when different approaches have the best results when working with A.I. or bots.

What biases should I be aware of when making important decisions?

| Bias | Description |

|---|---|

|

Confirmation bias |

The strong human tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms one's pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses. It causes individuals to give less consideration to alternative possibilities or counterarguments. |

|

Over-confidence bias |

An unwarranted belief in one's own abilities, judgments, or the accuracy of one's predictions. This can lead to underestimating risks and making decisions without sufficient deliberation. |

| Anchoring bias |

The cognitive tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered (the "anchor") when making decisions, even if that information is irrelevant. Subsequent judgments are then adjusted around this initial, incorrect anchor. We speculate that A.I. can inadvertently do this when discussing pros and cons if a person does not consider their own reasoning. |

| Representativeness heuristic/bias |

A mental shortcut where people assess the likelihood of an event by comparing it to an existing prototype or stereotype in their minds. This can lead to overgeneralized beliefs and overlooking statistical probabilities. |

| Availability heuristic/bias |

The tendency to overestimate the likelihood of events that are easily recalled or vivid in memory, often due to recent exposure or emotional impact. This can lead to neglecting a thorough search for other, potentially more relevant, information. Again, A.I. without a theoretical frame may inadvertently trigger this. |

| Negative information bias |

The psychological phenomenon where negative information or experiences are given more weight, attention, and impact on a decision than positive information, even when the positive information is equally significant. |

|

Status quo bias |

The preference for keeping things the way they are, avoiding change, and resisting new actions or decisions, even if a change might be beneficial. This bias makes people default to existing options. Example: Sticking with your current phone carrier despite a competitor offering a better deal, simply because switching seems like too much hassle (i.e., thus becoming a strong con reason in behavioral reasoning theory). |

|

Implicit bias |

Potential unconscious attitudes and stereotypes that affect our actions. Unlike explicit bias, which is presumed to be conscious, implicit bias operates outside our awareness. This may influence our decisions when we are highly uncertain about a behavioral choice. Example: A person can genuinely state that they believe in equality yet still act in ways influenced by their hidden biases. |

|

Authority bias |

The tendency to attribute greater accuracy to the opinion of an authority figure (unrelated to its content) and be more influenced by that opinion. Example: Following advice from a well-known expert without critically evaluating it, simply because of their perceived status. |

|

Optimism bias / wishful thinking |

The tendency to be overly optimistic about the outcome of planned actions, believing that positive events are more likely to happen to oneself than to others, and negative events are less likely. |

What situations should I be aware of when making important decisions?

| Situation | Description |

|---|---|

| Intense moods or sudden time pressure |

Extreme emotional states (like anger, excitement, or stress) or unexpected deadlines can impair carefully reasoned thought, possibly leading to impulsive or poorly considered choices (e.g., “oops, I didn’t think of that before I made the decision”). |

| Risk aversion |

A preference for a sure outcome over a gamble with a higher or equal expected value. When triggered, this bias can lead to an unnecessary delay in making a needed decision or choosing a less optimal but seemingly "safer" path. |

| Primacy and recency effects |

These describe how the position of information in a sequence affects memory and influence. The Primacy Effect refers to the tendency to remember information presented at the beginning of a list or sequence more strongly. The Recency Effect refers to the tendency to remember information presented at the end of a list or sequence more strongly. Both can distort the overall perception of information. |

| Analysis paralysis |

If you find yourself overwhelmed, mentally exhausted, or repeatedly going over the same thoughts without new insights, it's often helpful to step away, at least temporarily, or keep moving through the calculator. Taking a break allows your mind to clear, reset, and approach the decision with a fresh perspective. The old adage “sleep on it” can also be helpful to gain a fresh perspective if you have time. Continued "over-analysis" can lead to "analysis paralysis," where excessive thinking prevents any decision from being made at all. The calculators have TIPS inside to help manage this, especially the extended version. |

| Sunk cost fallacy |

The tendency to continue investing time, money, or effort into a decision or project because of resources already invested, even when it's clear that continuing is not the best course of action. It's the reluctance to "cut your losses." Example: Continuing to fix an old car that constantly breaks down because you've already spent so much on repairs, even though buying a new, reliable car would be cheaper in the long run. |

| Framing effect |

The tendency for people's choices to be affected by how information is presented or "framed," rather than by the objective facts. A decision can be framed to emphasize potential gains or potential losses. Example: A surgery with a "90% survival rate" sounds more appealing than one with a "10% mortality rate," even though they convey the exact same statistical information. Losing $5 can also feel worse than the happiness of finding $5 for many people, even though it's the same value. |

|

Groupthink |

A psychological phenomenon that occurs within a group of people in which the desire for harmony in the group or conformity with an authority figure results in an irrational or dysfunctional decision-making outcome. Individuals suppress dissenting viewpoints to maintain group cohesion. |

| Dunning-Kruger effect |

A cognitive bias where people with low ability at a task overestimate their own ability, and highly competent people tend to underestimate their relative competence. Example: Someone with very limited knowledge in a field confidently making a complex decision, unaware of the vastness of what they don't know. |

| Bystander effect |

A social psychological phenomenon in which individuals are less likely to offer help to a victim when other people are present. The greater the number of bystanders, the less likely anyone is to help. While often applied to emergency situations, it can translate to decision-making where individuals feel less personal responsibility to act if others are around. Example: In a team meeting, no one raises an issue with a proposed plan because they assume someone else will. |

| Halo effect |

The tendency for an impression created in one area to influence opinion in another area. A positive impression of one trait (e.g., attractiveness, friendliness) can lead to a positive impression of other unrelated traits (e.g., intelligence, honesty). Example: Automatically assuming a well-dressed and articulate person is highly competent and trustworthy, even if you have no direct evidence of their skills. |

How else can I be proactive in my own decision making? Many of the following topics are also addressed as you complete the calculator, especially in the extended version:

- Revisit decisions when possible: If circumstances allow, come back to the calculators or re-evaluate your decision, especially if you're stuck in uncertainty and need more information. It sometimes takes just one new reason to dramatically change the direction of the reasoning summary. Getting your reasoning as correct as possible can thus be impactful.

- Evaluate reversibility: Consider if the decision can be undone. Knowing a decision is reversible can alleviate pressure and help you move forward.

- Consider time limits: Determine if you need to set a deadline for making the decision, especially if there's a cost associated with delaying.

- Consult your network: When needed, seek input from trusted individuals in your network or reach out to those with relevant skills. We often underestimate people's willingness to help.

- Use technology wisely: Leverage technology for information gathering, but scrutinize its accuracy and be aware of what it might not be showing. Be cautious that AI could unintentionally bias you toward a middle ground if it presents both sides without knowing your starting point.

- Consider longer-term decision trees: For relevant decisions, think about potential future scenarios (e.g., "If I go down path X, Y, and Z, what will happen?"). Be mindful that this can also lead to decision paralysis if the chain expands too much.

- Review past decisions: Reflect on what happened in the context of this decision and who was involved. This can help you learn for future decisions, especially similar ones.

- Identify additional information needed: As you list your primary and counter reasoning, gaps in information often become clear. Gather this information to help finalize your reasoning.

- Consider short- and long-term outcomes: Think about the immediate and distant consequences of your decision. Ask yourself what respected experts would say, and how this decision connects to your overall goals and other important life choices.

- Prepare an action plan: Have a plan ready for implementing your decision. This can also reveal further consequences as you think through the practicalities.

- Make progress and find satisfaction: Making progress often correlates with satisfaction and happiness.

- Be ready to adjust: Be prepared to modify your decision or implementation if things don't go as planned or your initial reasoning was flawed. Avoid over-commitment if a strategy clearly isn't working after multiple evaluations.

- Seek trusted input: When a decision is highly important and impacts many stakeholders, consider taking a step back to get input from knowledgeable and skilled people you trust. Build a reliable team around you and remain open to valid counter arguments, while also being mindful about how power dynamics may influence you and your group.

- Adopt a probabilistic mindset: Recognize that anticipating a complex world is difficult. It is far more complex than dichotomous thinking. Trying to avoid perfectionism may be helpful, which may lessen disappointments, if they occur. Be adaptable and kind to yourself, understanding that many factors may be beyond your control.

- Carefully read the TIPS in the calculator as you work through it. These tips are connected to your actual responses, so it should make all this information more relevant as you proceed with your actual decision making.

(c) J.D. Westaby. All rights reserved. (beta testing launch version)