by BrightFlame

What if the Earth has a voice in your work and the way you live your life? What if you connect with the Earth, with Nature, with all living beings as dear friends? You likely have a scientific understanding of this concept: we are all part of (not separate from) the ecosystem.

Beyond science, feel the Earth in yourself, for we are all connected as this organism we call planet Earth.

Ecosystems nest within and overlap one another collectively forming our biosphere. All species, all of life, are part of the whole. Visualizing the biosphere as a web reminds us of the complex connections among all the parts—including us humans. Alter any one part of this web and you affect all.

The Web of Life: understanding and acting from this concept is foundational to bring forward a regenerative future.

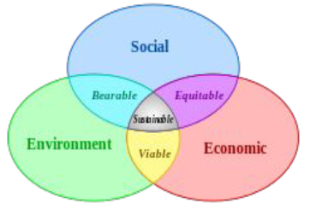

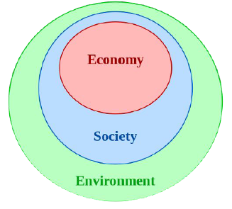

My role at the Center for Sustainable Futures (CSF) is to help us build from this concept and to amplify Earth’s voice as input for action—from crafting syllabi to developing programs to designing our research. To start, let’s look at the Center’s unifying statement: we envision a regenerative world in which we achieve a balance between planet, people, and prosperity. As my colleague Oren Pizmony-Levy points out, sustainability is often portrayed as three pillars: economy, society and environment, a Venn diagram of three overlapping circles. Some, including CSF, have reframed the model to show the environment as the outer and overarching of concentric circles; all parts nest within the Environment.

Still, this simple diagram is imperfect. It implies an anthropocentric view of the world: that we are in the Anthropocene is the problem, is the key hazard that endangers a regenerative future.

Perhaps you’ve seen the image of a human in the middle of a circle of all other living beings: the human is centered and dominant. Juxtapose this human-centric image with one depicting a human in the circumference among all living beings: this is the reality of the Web of Life and describes the healthy, regenerative mode.

Yet humans often live and develop society through the lens of the first schema—being at the center, dominating the circle of life. We find a key poisonous root of such behavior in the Doctrine of Discovery. Make no mistake: this doctrine was crafted for profit-making, not from a benign spiritual belief. It justifies racism, colonization, domination, and violence against humans and other living beings, including the natural world. The colonizing of Europe, Africa and Asia began long before conquerors arrived in the Americas. The 15th century doctrine was not new—it codified the system of thought and action that crept into human culture in the Neolithic, ultimately bringing on the Bronze era.

Developing a reciprocal relationship with all life is key to de-doctrinizing, decolonizing our work and our lives.

I have been working on this article for some time, noticing I’m writing in circles and trying to straighten out my thinking. But Earth says, curves and spirals are the shapes and flow of Nature. Circling back like the hawk overhead is purposeful, is aligned with life.

I highly recommend scientist, professor, and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation Robin Wall Kimmerer’s landmark book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Not only does she offer wisdom and different ways of knowing, she spirals around key concepts through storytelling. This way of storying science offers more layers of meaning than would a simple linear treatise. It is in the braiding that her story opens us to contemplate and feel our way into relationship with Mother Earth and all beings.

Reciprocity is foundational to most Indigenous Peoples’ ways of life. Kimmerer weaves intuitive and scientific examples of reciprocity throughout Braiding Sweetgrass. One story among many: weaving a basket is more than a metaphor for weaving well-being for land and people. It is a prayer, a setting of intention, a way to reinforce our understanding of the Web of Life. As you begin to weave:

Ecological well-being and the laws of nature are always our first row. Without them, there is no basket of plenty. Only if that first circle [the base of the basket] is in place can we weave the second . . . material welfare, the subsistence of human needs. Economy built upon ecology. But with only two rows in place, the basket is still in jeopardy of pulling apart. It’s only when the third row comes that the first two can hold together. Here is where ecology, economics, and spirit are woven together. By using materials as if they were a gift through worthy use, we find balance. I think that third row goes by many names: Respect. Reciprocity. All Our Relations. I think of it as the spirit row. Whatever the name, the three rows represent recognition that our lives depend on one another, human needs being only one row in the basket that must hold us all. In relationship, the separate splints become a whole basket, sturdy and resilient enough to carry us into the future. (p. 153)

I am a white settler on this continent and live on Lenape lands. Being in right relationship with the Earth means connecting, putting my roots in the ground, cultivating my relationship with the land. Yet, I am not an Original person of this continent, not Indigenous here. What does indigeneity mean for me?

Discussing reciprocity in Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer says, “For all of us, becoming indigenous to a place means living as if your children’s future mattered, to take care of the land as if our lives, both material and spiritual, depended on it.” (p. 3)

Eminent ethnobotanist, artist, scholar, and educator Dr. Gregory Cajete, a Tewa Indian from Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico, in a 2009 interview suggested non-Indigenous people “look at these traditions of Indigenous people and begin to understand them with respect, responsibility, resonance and relationship. Because ultimately, we are all Indigenous at some time in our life and culture. Even the cultures of the West are Indigenous at a certain point in their history.”

Rain is dripping through fluttering leaves, calling my attention. The rivers in the sky are speaking with the rivers in the Earth just as nature speaks with all of us—we just need to learn the language. Those of us who are not Indigenous can look to Indigenous traditions for help learning the language and finding our way into relationship without appropriating ceremony and stories.

Ethnoecologist and executive director of Earth Timekeepers Geraldine Patrick Encina defines ethnoecology: “an interdisciplinary field of study that enables a human group with a land-based culture to share how they conceive the ecosystem they inhabit. . . . In all instances, what characterizes the human groups is the way in which they perceive the web of life and conceive their participation in it. They have come to understand, from accumulated experience, that dynamic processes are constantly shaping the way they see and interact with the natural world.” She describes a detailed mapping of skyscapes, landscapes, and subsurface underworlds where tangible and intangible aspects are equally relevant. These include spiritual aspects (belief and value systems and a reverence for Mystery and the unseen); knowledge acquired about the natural world (including science, mindful attention, and intuition) and practice (interaction with the natural world).

In “The Rescue of the Spirit and of Nature,” research scientist and ethnoecologist Victor M. Toledo attributes the negation of spirit and the destruction of nature as the two-pronged root of the massive challenges we face today. Finding one’s spirituality arises from “the recognition of a vital force that moves everything and to which all members of the human species are indebted. Without exception, this worldview was present in all the cultures that made up humanity during its almost 300,000 years of existence.” For most of that time, cooperation led human evolution and survival. He concludes his cautionary article: “The two central tasks of every conscious individual are the rescue of spirituality and (re)connecting with respect for nature. Three sectors are playing a strategic role in this: environmentalists, women, and indigenous peoples. In them are found the sources of inspiration and subversion needed to construct a different civilization.”

For decades, I have kept my professional career separate from my spiritual life. The Earth has asked repeatedly why I pull myself apart. The core of my spirituality is that the Earth is sacred and we are all part of the Web of Life. As you might note from this article, I have reconciled the parts of my life and come into resonance with myself; now, I am more often in resonance with the Web of Life.

Cajete has dedicated his work to honoring the foundations of Indigenous knowledge in education. In a 2015 talk at the Banff Centre, part of the Indigenous Knowledge and Western Science event, he guides us in circular form (his words), to understand Indigenous science, a metaphor for Indigenous thought. He says Indigenous science is not a way to explain away the mysteries of the natural world, it is a way to resonate with the natural world, noticing interconnections and relationships, noticing the dynamic energy of the cosmos.

The skills of my spiritual form—including deep listening, perceiving through more than the five physical senses, and conversing with other forms of life—bring me in resonance with the Web of Life. Our world is ever-changing, cycle upon cycle, in flux. To know it and feel our relationships with all beings, we come into resonance with the Web. It’s not a static state: we fall in and out of resonance. Our bodies, our minds, our spirits know when we are in resonance and when we are not.

Being resonant with the Web of Life is foundational to bring forward a regenerative future.

Like Cajete and other Indigenous scholars, Kimmerer weaves Western science with Indigenous ways of knowing, showing that it is not one or the other. Indigenous ways of knowing bind heart and reason, intuition and intellect. Megan Bang, Ananda Marin & Douglas Medin offer in their Dædalus essay, “Indigenous sciences are foundationally based in relationships, reciprocity, and responsibilities. These sciences constitute systems of knowledge developed through distinct perspectives on and practices of knowledge creation and decision-making that not only have the right to be pursued on their own terms but may also be vital in solving critical twenty-first-century challenges.” [emphasis mine]

We hold that Indigenous sciences are no less objective than Western science; they value truths, not agendas. Indigenous science operates around a set of values, as does Western science. Values enter into the practice of science in all kinds of ways, including decisions about what to study and how to study it, the framework in which findings are interpreted, and how knowledge ought to be shared. “Objectivity” therefore cannot and should not be equated with “value-neutrality.” We must pose the question: whose values and whose knowledge systems are accepted as legitimate in a multi-cultural, multi-epistemological world? . . . We propose that the practice of excluding the values and methods of Indigenous science from science and from society more generally poses significant dangers, not only to Indigenous peoples but to all peoples. [emphasis mine]

Indigenous science and education are in right relationship with Earth and antithetical to a human-centric, colonized way of being. Indigenous scholars like those I mentioned, above, have pointed this out for decades. There are a growing number of Indigenous educators teaching Native Science in colleges and universities. In his 2015 talk, Cajete points out that Native Science is a metaphor for Native Knowledge. Stories “include creative ways for living and participating in relationship with the world through processes for seeking life, relationship and meaning.” An Indigenous scientist “not only observes the world but participates in it with all of [their] sensual being. Everything in Nature is ‘alive’ with energy. Therefore becoming open to the natural world with all of one’s senses, body, mind and spirit is the goal of Native Science.”

The Indigenous scientist learns how to resonate with place, community, cosmos. I am grateful for the growing number of educational institutions that center Indigneous voices and teach Native Science. I imagine a just and sustainable world quickened when concepts and experiences of reciprocity, resonance and responsibility are embedded in core K-12 curricula. I found my way to such practices over decades; I give back by tending land as a native plant sanctuary and through teaching. I’ve developed exercises that help others experience Nature as family.

In the Indigenous educators article, Cajete mentions that his graduate students are angry a nature-centric, long-view approach is not part of their early education. “Science is a human knowledge system; it can change. Education is key. Education is what caused the condition in the first place and education can correct that. . . . It’s developing very slowly. But it’s developing and moving forward.”

In a 2020 interview, Encina advocates that biocultural territories “can be healed when human communities are permanently cultivating their spiritual connection to the land that hosts them.”

What is your relationship with the land, with the Web of Life?

As I was attempting to finish this article indoors, Earth said, go outdoors where you can smell us. And so I’m sitting among the trees and plants and birds near my home at the end of October. The composting fallen leaves, the wet soil from yesterday’s rain, brighten a fecund scent that tastes metallic, organic, healthy. Under a cloudy sky, the red sassafras, the golden hickories and bronze oaks draw my eyes and open my heart. I find resonance with all life. I fall in love with the Earth all over again.

I will leave you with Robin Wall Kimmerer’s words:

The most important thing each of us can know is our unique gift and how to use it in the world. Individuality is cherished and nurtured, because, in order for the whole to flourish, each of us has to be strong in who we are and carry our gifts with conviction, so they can be shared with others . . . In reciprocity, we fill our spirits as well as our bellies.” (p.134)

What is your gift to a regenerating and just world?