By Maica Mori

Maica Mori is a recent graduate of the University of Michigan. Maica contacted the Center for Sustainable Futures for background conversation as part of her coursework in Environmental Journalism (ENVIRON320; instructors: Emilia Askari and Julie Halpert).

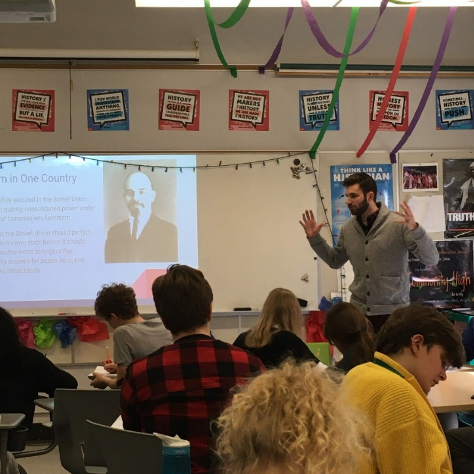

Silvester, teaching students in the classroom

Ryan Silvester, a Social Studies teacher at Ann Arbor’s Community High, greets students and silently counts their numbers as they file into the classroom from their open-campus lunch break. The bell rings and, clearing his throat, Silvester refreshes the high schoolers on last week’s topic and introduces the focus of today’s lesson. Down the hall in the teacher’s lounge, his colleague Sarah Hechler is using her break to prepare for her World History class.

Beyond just preparing and teaching today’s lessons, though, Silvester and Hechler have already begun improving their lessons for next year. For the last few months, these teachers have been studying environmentally focused textbooks and online learning platforms that will help them implement Michigan’s new Social Studies Standards published last summer. While both the 2019 and 2007 standards introduce climate change explicitly in 6th grade, the hotly debated new standards mention climate change six times between middle and high school curriculum (four more times than the old standards). Both Silvester and Hechler are working hard to meet these Social Studies Standards, and they hope to see climate change taught across the disciplines as well. “Why can’t we have an environmental spin on English or on Math?” asks Silvester.

There’s a reason why climate change has not been embraced throughout Michigan’s core curriculum standards. “Legislators are trying to infuse themselves into the conversation for various reasons, some of which are ideologically based,” Casandra E. Ulbrich, President of the State Board of Education, says while discussing the effects of partisan-influence in writing state standards. “The last thing you want is for education to become a political hot potato where there's huge swings from year to year on what gets taught and why it gets taught.”

President Ulbrich is referring to how Americans’ perceptions of climate change link to partisan politics, as indicated by polls. According to a study done by the Pew Research Center, 78% of Democrats say dealing with climate change should be a top priority, as opposed to 21% of Republicans. Glenn Branch, deputy director of the National Center for Science Education, weighs in on this history of controversy, specifically regarding the Next Generation Science Standards, or NGSS, which acknowledge climate change more heavily than others standard guidelines. “Michigan was actually one of the first state legislatures to have a bill that would have blocked the adoption of NGSS. This was back around 2011, 2012 or so. That seemed to be basically driven by conservatives in the auto industry. That bill did not pass but we've seen bills like that in many other states and with some lasting success in states with large extraction industries - West Virginia, Wyoming, and Texas (although there it’s the state board of education that's doing the heavy lifting rather than the legislature). We've certainly have seen partisan attacks on the inclusion of climate change in science education, and almost entirely from the right wing and Republican party.”

In Michigan, Republican former state Senator Patrick Colbeck from Dearborn, MI opposes teaching anthropogenic climate change as a definite scientific fact. “I'm not coming at this position as a state senator,” says Patrick Colbeck, Republican and former State Senator of Michigan. “I'm coming at it as somebody who worked in industry for almost three decades, who had an accomplished career in engineering working on environmental control systems, realizing how difficult it is to actually manage our environment,” says Colbeck. Colbeck stands by his proposed revisions to Michigan’s Social Studies Standards that were heavily debated and eventually disregarded in favor of the official 2019 version. “They were pushing more of a political ideology instead of critical thought,” says Colbeck. “For people to jump into a policy discussion around our environment without having a solid understanding of how the environment works, it's dangerous. Very dangerous.”

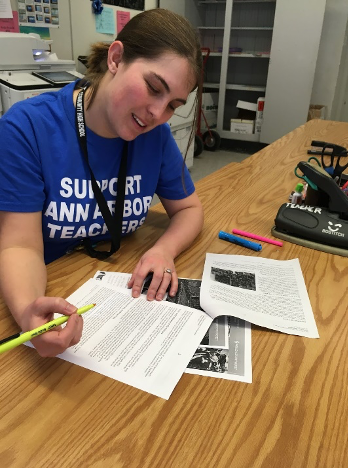

Hechler, reviewing her World History lesson plans

Still, both Silvester and Hechler believe climate change should be introduced to students as early in their K-12 journey as possible, and they are not alone. A survey conducted by the National Public Radio and Ipsos, a market research company, found that 86% of K-12 teachers believe climate change should be taught in schools. Roughly half of K-12 teachers polled believe the curriculum should begin in kindergarten or elementary school. It isn’t just teachers who want this for students. A separate study co-run by NPR and Ipsos found that 78% of American adults felt similarly, and the number rose to 84% for those with children under 18. And according to a study conducted by Columbia University Professors Oren Pizmony-Levy and Aaron Pallas, 77% of American adults believe teaching climate change in primary and secondary schools is important.

According to Pizmony-Levy, climate change will not be widely taught in the classroom until it is required by standardized testing. “I really see the link between not teaching climate change and testing. It's like blinders on a horse – it’s limiting the schools to do very specific tasks,” Pizmony-Levy points out. “Maybe we need to focus more on testing climate change which is the issue of the day.” He also encourages adopting a multi-disciplinary approach to teaching climate change. Professor Angela Calabrese Barton of University of Michigan’s Educational Studies Department totally agrees. “Science often takes the back seat to political and religious views. That’s why we need an interdisciplinary perspective to support students in navigating that complex terrain with their decision-making,” she says. Calabrese Barton advocates for more support from administration for teacher collaboration across disciplines and project-based teaching on the local, tangible impacts of climate change. “Research shows that a lot of people can’t understand the gravity of climate change because they can’t see its impact on them,” Calabrese Barton says.

But when people, including children, can see that direct impact on their life, it certainly hits home. When asked about her daughter’s understanding of climate change, mother and Editor/Publisher of Planet Detroit, Nina Ignaczak, says, “I first realized my daughter was upset about climate change when we visited the beach at Empire, MI that we have been coming to every summer since she was a baby. The beach is highly eroded and sand dunes are gone. She sat down and cried and expressed anger about climate change when she saw it.”

“If we don't take action now, and we get to the point where people decide, 'Oh, this really is a problem!', it's probably too late. It should have happened some time ago,” says Dennis Schatz, President of the National Science Teaching Association. “I'm one of those older members of the population who aren't going to be here to really feel it. But my grandchildren, whom I think about a lot, who are eleven and 8, will be. They're the ones who are going to feel it.”

Back in Community High, the social studies teachers find reason to be positive about the future – under a changing climate – that their students will help shape. “It's an upsetting process and it's going to take a while,” says Hechler. “Our students know that for better or worse, we’re going to see a lot of change in our lives. But it can be an exciting proposition and they can be part of the change, and I think they know that. And that fills me with hope.”

Silvester also finds hope in his students but believes that there still needs to be more change. “Climate change and environmental history need to be taught. The changing of the [state Social Studies] Standards gives me hope. Seeing student activism gives me hope. But we’re not there yet.”