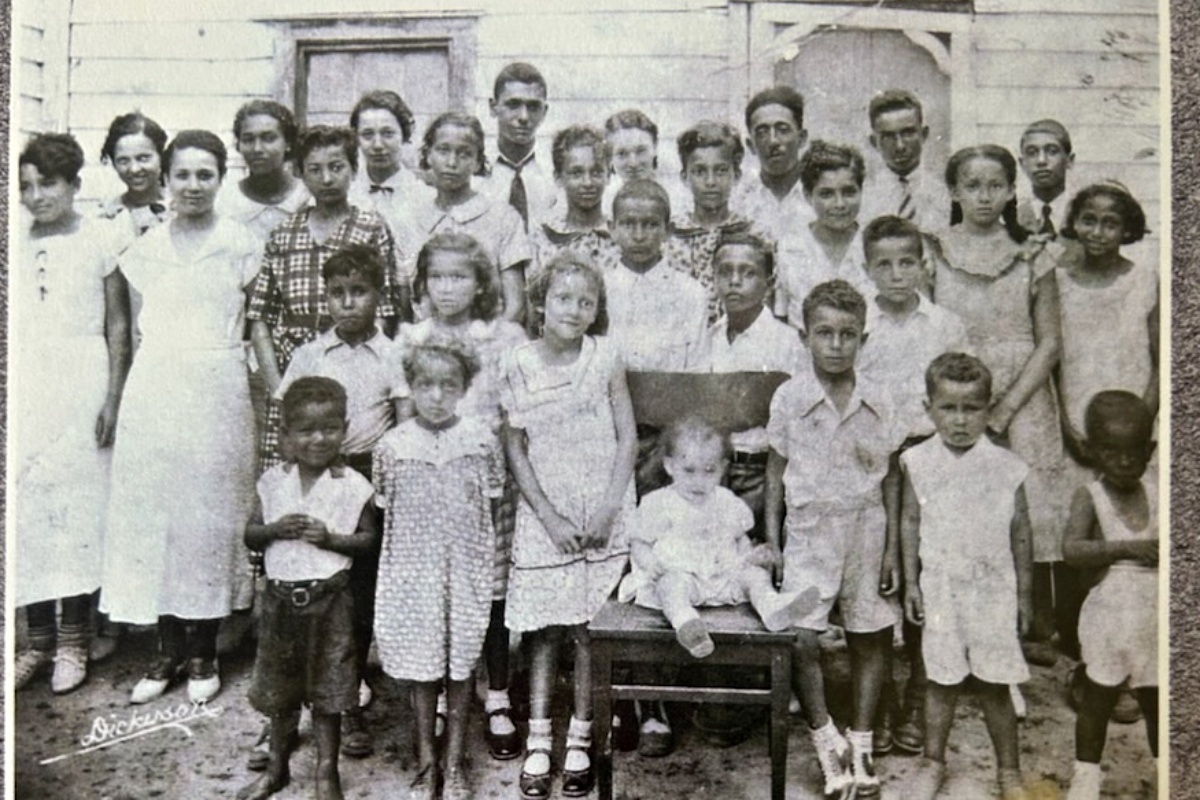

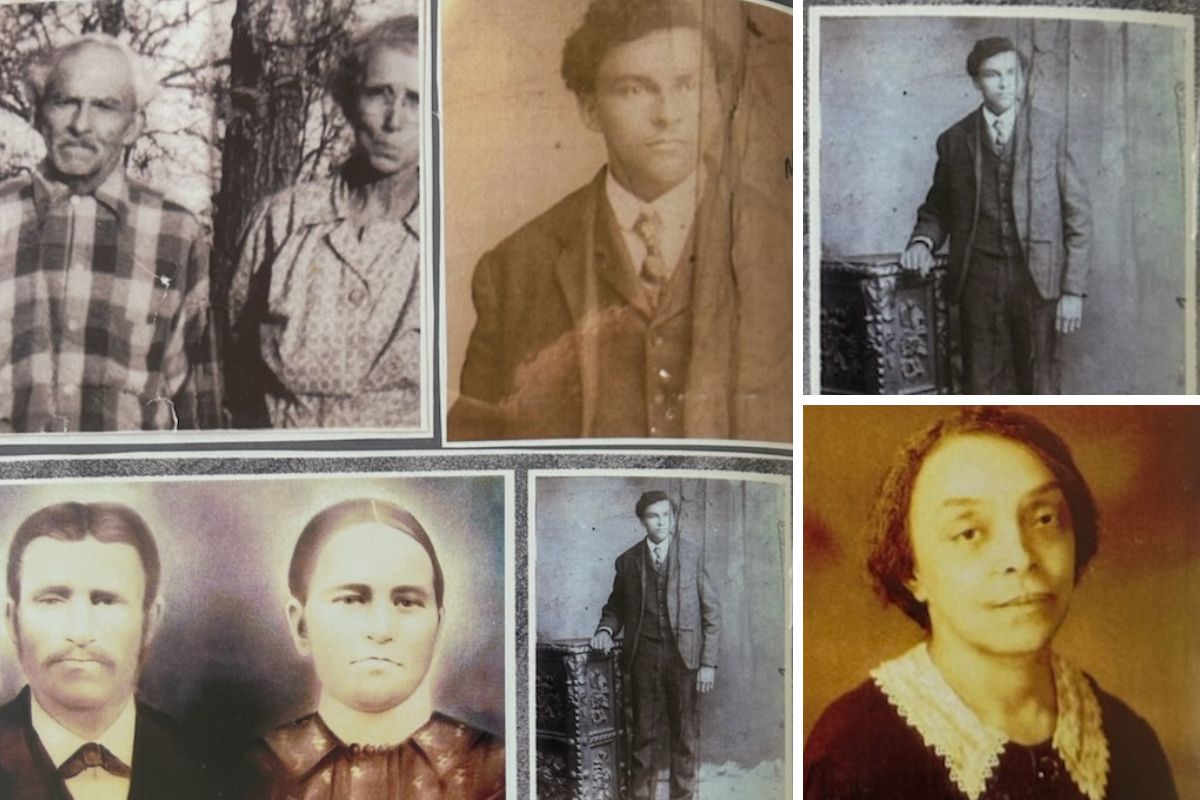

A homemade scrapbook led Deanne Green (Ed.D. ’26, Curriculum & Teaching) to dive deeper into the tangled web of historical American laws and social limitations that shaped her family.

Green always knew that she descended in part from the Pamunkey Indian tribe, though its customs didn’t play a role in her upbringing. But during the pandemic, she and her cousins discovered: “We’re a lot more native than we think.”

As a Black-Indigenous family in Virginia, generations of Greens straddled two worlds, but were forced to largely unsubscribe from their Pamunkey roots. The state’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924 was one of several methods that systematically disenfranchised biracial people by forcing individuals to identify as either white or “colored,” and outlawed interracial marriage. Simultaneously, Indigenous tribes across the country had their own incentives for making tribal membership less inclusive, and today still regularly strip multiracial Indigenous people of tribal status.

Now, Green is devoted to amplifying the experiences of Black-Indigenous scholars in the United States. Her dissertation research leverages qualitative research methods to explore how education has shaped their identities from early childhood through higher education. Against the backdrop of ongoing questions regarding identity in school, Green is in dialogue with two central questions:

“What does it mean to have these two ethnic and racial identities show up in a classroom? And do we have the resources to support these students in showing up in these spaces?” explains Green, a former research assistant at the Edmund W. Gordon Institute for Advanced Study. “I want to put primary resources about Black-Indigenous scholars into academic and historical spaces.”

The visibility and nuances of their experiences are particularly critical as graduation rates for both Indigenous and Black students fall below national averages. “If you’re Black-Indigenous and made it to higher ed or grad school, you’re overcoming some hurdles statistically for me to even sit down and be interviewed by you,” says Green, who sees her work in direct opposition to neocolonialism. “You have to break a pattern with a counter-story. Black-Indigenous students have these other experiences that are good, bad, ugly, beautiful, and joyful…what does it look like contemporarily in 2025?”

Green’s research journey began in a different place. She originally wanted to study maternal morbidity among Black and Indigenous mothers before pivoting to her current focus. Along the way, Green has had the opportunity to work closely with a number of TC faculty who have profoundly influenced her academic life. Felicia Mensah, Professor of Science and Education, offered support through the Black Student Network and gave Green a foundation in qualitative research methods. Green’s academic advisor, Assistant Professor Tran Templeton, “supported [her] on a more emotional level.” Bettina Love, the William F. Russell Professor and one of Green’s dissertation advisors, has been the “secure base” that Green says she needed, while Rachel Talbert, Research Assistant Professor, guided Green through her first conference and “opened [her] eyes” to the power of peer review.

What does it mean to have these two ethnic and racial identities show up in a classroom? And do we have the resources to support these students in showing up in these spaces?

“Deanne’s work with college students is really important. She’s doing a lot of work that is envelope-pushing in the field,” says Talbert, noting how Green’s work builds on developments in the field and is “extending so much of the conversation that needs to be happening.”

Talbert helped Green and other doctoral students prepare and practice for their first presentations at the annual meeting for the Journal of Curriculum Theorizing where Green would meet another key scholar in her journey: Purdue University’s Stephanie Masta, one of the foremost experts on Indigenous methodologies in educational spaces, who would serve as Green’s other dissertation advisor.

“Your first conference experience is really important. I always wanted to make sure to encourage them to present and demystify that for them,” says Talbert, who says she learns from her students as well. “It was great to see Deanne present in front of a lot of senior scholars, and I remember being so thrilled to see her talking with Dr. Masta and knowing she could really hit a home run out of the park with her research.”

As for what will come after Green graduates from the College, she plans to continue her work with Indigenous and Black populations in international contexts — seeing opportunities for additional academic collaboration across the globe. “You have Indigenous people all over the planet who are rising up against imperialism,” says Green, who has no shortage of ideas “if [she] dreams without limits.”