by BrightFlame

I’ll convey in this article why I’m so taken with solarpunk, and why it’s relevant for education, especially Environmental and Sustainability Education (ESE). I include links to many resources that I hope you’ll explore at your leisure once you read this article.

While solarpunk is a broad movement, an evolving container, and purposely not easy to define, it is also a literary subgenre. So, first, a bit about storying—or re-storying—the future:

Change the story, change the world

What is the future you desire for generations forward? Let your mind wander, your imagination flow. Let images emerge, listen to the sounds around you, notice smells and movement as you explore. Notice:

terrain,

ecosystem,

natural world,

water sources and flow,

food and power production,

structures, homes, gathering spaces,

community composition and activities,

transportation and other infrastructure,

relationships with nonhuman living beings.

To create the just, regenerative world we want, we need to make it real in our minds, to point ourselves towards it, and to help others widen their view of the possible. Storying the future is an important tool for changing the world.

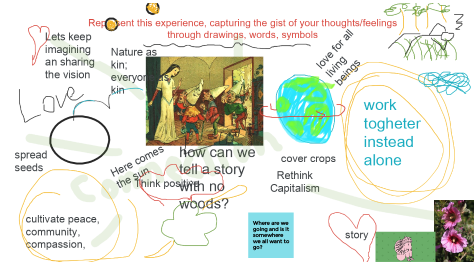

I offered an experiential workshop for our Center’s international collaboration in December 2020 that included visioning a sustainable future using some of the prompts in the previous paragraph. The collaborative image created by participants captures a small slice of their imagined futures:

I refer you to my workshop and its accompanying slides for more details about the importance of and cognitive science of story to affect our lived experiences, motivations, and actions.

Towards Hope

There is a trend away from dystopian fiction and towards work depicting hopeful, achievable futures. For instance, amidst declarations from publishers that dystopia is a dead genre now, a quick scan of literary agents’ wish lists yields calls for hopeful stories and “No more dystopia. Please.” This follows research that shows action for the environment and a sustainable future is influenced by feelings of hope, while despair about a bleak future garners inaction and despair. As editor Sally Weintrobe says in the volume she edited, Introduction to Engaging with Climate Change: Psychoanalytic and Interdisciplinary Perspectives (Taylor & Francis Group, 2012) “Our thoughts may be distorted by unconscious processes, which include defences against knowing what we feel and think as a way of protecting ourselves from facing ‘too much reality’.” In other words, shutting down at the notion of a bleak future and distancing ourselves from the state of the world when overwhelmed with climate change science (and fascism and injustice). Chapters in the book elucidate anxiety and apathy responses when faced with climate change and our real-world dystopian trajectory.

In “Hope and anticipation in education for a sustainable future,” Maria Ojala distinguishes between existential hope and critical hope. The former based on trust that everything will work out: more like wishful thinking. Critical hope is grounded in reality, a protest of what is, and a promise of a better way that might lead to goals and trajectories. A third road lies between these two types of hope: utopian hope is goal-oriented and “based on desires for alternative collective futures.” Laila M. Strazds pushes this notion further, discussing radical hope, which positions between critical hope that proposes a point of departure and goal-oriented transformative hope that proposes an end point. Radical hope “is rooted in context, provides a point of departure, and is realized through action.” She writes, “Sustainability is in the process of becoming and it is through pedagogies of hope that its realization is taking place.”

I am buoyed by the growing number of authors writing hopeful futures with real solutions, a subgenre of climate fiction: solarpunk. I’m also lifted by the many who are making it real, working in the commons to change the world.

Definitions and Importance of Solarpunk

In Solarpunk: Notes toward a manifesto, Adam Flynn writes “We’re solarpunks because the only other options are denial or despair.” (He opens the manifesto: “It’s hard out here for futurists under 30.”) He continues:

Solarpunk is about finding ways to make life more wonderful for us right now, and more importantly for the generations that follow us—i.e., extending human life at the species level, rather than individually. Our future must involve repurposing and creating new things from what we already have (instead of 20th century “destroy it all and build something completely different” modernism). Our futurism is not nihilistic like cyberpunk and it avoids steampunk’s potentially quasi-reactionary tendencies: it is about ingenuity, generativity, independence, and community.

As I said up top, solarpunk by definition is evolving and not a static, defined aesthetic. As some have said, defining it limits it.

Jay Springett, a consultant strategist and writer, gave a very interesting presentation about solarpunk. Key takeaways for me: solarpunk is a growing container where gravity pulls some core, mutually understood concepts towards the center, and ideas around the edges are more blurred and in flux—this, by design. It’s an aesthetic of many voices; as such, solarpunks can speak only for themselves, not the movement as a whole. Jay says in the presentation

Solarpunk asks: What if we together, collectively, create a container that can be used by anyone to place their ideas about the future inside. And what sort of stories would that container with the things it contains, create?

He calls solarpunk a memetic engine that re-futures participants’ imaginations.

As solarpunk is a movement, an aesthetic of many voices all in relation to one another and not definable by any one person, I asked some wonderful people involved with solarpunk to share their thoughts for this article.

Sarena Ulibarri (she/her) is a speculative fiction writer and the Editor-in-Chief of World Weaver Press, whose collection includes four solarpunk anthologies to date. Sarena shares:

Solarpunk is a movement of artists, writers, and activists interested in changing the trajectory of our world for the better. As a genre of fiction, solarpunk comprises optimistic science fiction stories that engage with issues of environmental and social injustice. Solarpunk stories don't always elaborate on the specific solutions that led to a better world, but they do always strive to show that better futures are possible. Often paired with the aesthetic of Art Nouveau—which was historically an anti-capitalist movement—solarpunk worlds strive for a balance of nature and technology, with degrowth and decentralization as core values.

A lot of climate fiction focuses on the disasters and the dystopian outcomes of climate change and ecological collapse. Solarpunk doesn’t ignore those issues, but it focuses on how we make the world better, and how we thrive and adapt in the world we’re headed into. It’s an interruption of the narrative that we are doomed and there’s nothing we can do about it. Negative messaging about climate change tends to make people feel hopeless, and the cognitive dissonance produced when blame is pointed at individual action can actually bolster denialism. So solarpunk uses different tactics to try to get people’s attention. Rather than “if this goes on, here’s the worst that can happen,” solarpunk says, “if we change direction, here’s a better version of what could happen.”

Mary Woodbury (she/her) is a technical writer by day and fiction writer at night. Her website is a rich resource for all things eco-fiction, the umbrella term for many sub-genres—from stories about the natural world to mythic fantasy to climate dystopias to solarpunk. Mary offers:

Margaret Atwood once wrote that climate change is everything change. . . . for solutions to happen, they must address everything that is changing. Solarpunk seems to offer a multiplicity of, if not solutions, then ideas to begin addressing climate change via better ways of mitigating the worse effects of everything change. Solarpunk is the climb toward a better world that is realistic and possible. Many think solarpunk is utopian, but utopian is "no place" and not reachable. A better word might be "ustopia," which Atwood coined; it refers to something non-binary (i.e., not dystopia or utopia) but something combining both of these ideas that we (us) can do together. Another new concept is optopia, which refers to a more realistic version of a place we can reach, “the best possible world we can create.” Getting the opias out of the way, solarpunk takes place in multiple agencies: art, architecture, music, fashion, technology, literature, and more, which sort of underline the everything part of ecological and climate changes. It's a movement toward a better world in all aspects, building toward cleaner energy, more greenspaces, social justice, egalitarian ideas, and so much more. A degree of aesthetic is involved, but beneath it all is genuine concern for the well-being of everything and everyone. The punk part of it refers to the fact that we have to fight the current status quo of fossil fuels and other fossil ideas every step of the way.

Justine Norton-Kertson (they/he/she), writer, publisher, musician, photographer, and community organizer, is co-Editor-in-Chief of the new Solarpunk Magazine. They offer:

Solarpunk is a prefigurative, utopian artistic and activist movement that envisions what the future might look like if humanity solved major modern challenges like climate change, and created more sustainable and balanced societies. As a genre and cultural aesthetic, it encompasses literature, visual art, fashion, video games, architecture, and more. Solarpunk carries many aspects of punk ideologies such as rebelliousness, humanitarianism, egalitarianism, animal rights, decolonization, anti-racism, anti-sexism, anti-authoritarianism, anti-corporatism, and anti-consumerism. Similar to the cyberpunk genre, the big difference between the two is that in solarpunk technology and nature are in harmony with one another rather than in conflict.

Not all solarpunk stories take place in idealistic utopias. Many tales are rife with compelling conflict among people and communities optimistically striving to reach that ideal while still struggling to solve existing challenges. But all solarpunk stories do have things in common such as future or near-future settings, optimistic perspectives, and looking toward a better future with at least a growing harmony between nature, technology, and humanity. In short, solarpunk stories are decidedly not dystopias.

On their impetus for the magazine:

I started seeing the word solarpunk in articles from big media outlets like Yes! magazine, the BBC, and many others. These publications were putting out articles discussing the concept of solarpunk, and calling for more optimistic stories that provide solutions rather than ending in apocalypse. After searching and failing to find any solarpunk-specific science fiction and fantasy magazines, it seemed like it was important for one to exist to help the genre grow and become a larger force for change.

My dear friend and mentor Starhawk (she/her) is an author, activist, permaculture designer, and teacher who writes regenerative futures and creates projects and workshops to help us get there. She shares:

Too often, futuristic fiction is assumed to be dystopian, Mad Max warnings of doom. Outlets for any positive visions were hard to find, and hopeful stories were dismissed as naive. That’s why I was so thrilled to learn about the launch of SolarPunk Magazine! For how can we create a future we want to live in if unless we first imagine it? When I wrote The Fifth Sacred Thing in the early ‘90s, and its sequel City of Refuge twenty years later, I was consciously trying to envision what the world might look like if the ideals and values I held were put into practice. Fiction can be a great vehicle for thought-experiments—and maybe a few more of those and a bit less self-righteous dogma could help us out of this time of polarization! I’m so glad that there’s now a name for the genre: ‘solarpunk’! And so happy to contribute to this new magazine. [She is featured in Issue #1.]

Lunarpunk writer and artist Meira Datiya (they/them) is an editor at Optopia Zine. They share:

I think solarpunk is about creating a sustainable world for all species, human and non. One that brings us back in balance with our planet without sacrificing technology. And one that removes the barriers we have today of living up to our full potential. For example: capitalism, colonialism, racism, ableism, classism, etc. I find it heartbreaking that the concept of such a world is considered utopian and not our present lived reality. . . .

Solarpunk is anti-capitalist. There's no place for corporate backing in this movement. There's no place for crypto or NFT's or any profiteering. This movement is about hope in a future where people and nature are no longer exploited. That being the case, we constantly have to examine institutions, what kind of ideologies created them. This is about collaboration. Do we want to see the institutions that put us in the predicament we are in now still around in our future? Or do we create something that works for everyone and prevents these things from happening again? . . .

[The impetus for Optopia Zine:] If you can imagine it, you can make it possible. Optopia is here to show that people are doing both right now and that there's still hope that we can bring that better world into existence, despite how things may seem. I think [writer Ursula K.] Le Guin said it best when she said, "We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art, the art of words.”

Language has power and terms like optopia and ustopia are more aligned with solarpunk to me than is utopia. Especially since the history of Utopian writing and thinking sits squarely in white, masculine, resource-rich culture. Per my fellow educator and a lead organizer for Brooklyn Speculative Fiction Writers, Rob Cameron (he/him): “Many of the published ecological utopian stories of the early 20th century were toxically masculine, anxiety-driven, Eurocentric, and downright lethal.”

Which brings us to this:

Whose “Utopia” (or optopia or ustopia)?

Solarpunk frames itself antiracist, decolonial, anticapitalist, global, diverse, collaborative, grassroots, and aligned with equity- and justice-seeking individuals and groups. These are among the core qualities I mentioned, above, that float to the common center of the solarpunk container.

As Meira Datiya writes:

Solarpunk is anti-racist and decolonial. If you aren't working with your local communities and listening to what they have to say, you're doing something very wrong. White saviorism and white supremacy have no place in a solarpunk future, and to some extent, we have grown up with these being the norm. Whether in the open or in more subtle forms through our speech and learned behaviors. Question everything. A lot of people for example might think that homesteading is solarpunk, but it's colonialism. Others might ask local indigenous communities for ideas but then disregard them or believe their solutions are better. This isn't collaboration, it's not mutual aid, it's saviorism. You also need to be aware of the rise of eco-fascism which takes advantage of ecological ideas to promote genocide.

I’ve found that many solarpunk voices—at least the ones most commonly referred to including people I quote—are white. Rob Cameron explores the intersection of Afrofuturism and Solarpunk as he goes “In Search of Afro-Solarpunk”:

Afrofuturism and solarpunk have been around long enough to have met in a crowded SOHO bar and taken a selfie together. Yet here we are. What follows is an examination of the barriers between the two and how we might break them. . . .

The arc of history does not naturally bend towards justice. Neither does the trajectory of science fiction. Both must be bent. Producing and disseminating Afrofuturist stories and integrating them with sci-fi are integral to that great feat of emotional labor. However, there is no just future built atop (or buried under) the dystopian wreckage of an environment in freefall. Make way for Afro-solarpunk.

Kim Stanley Robinson calls social justice “survival technology” [in the Afterward of a 2014 volume], and it must be at least as advanced, exploratory, and revolutionary as the renewable energy research that consumes the majority of solarpunk discussion. Here again, Afrofuturism can fill a much-needed gap. Solarpunk creatives don’t need to reinvent the wheel; they need to communicate with the ones who built it the first time.

Rob adds further thoughts for us:

There are pockets of our reality where hopeful visions of the future are hoarded, and solarpunk has tended to come from those loci. To some extent that is okay and to be expected: the fruits of hemispheric, temporal, and economic hegemony. Naturally, here is where the ability to generate and disseminate ideas has had the greatest capacity and shaped output for over a century. We have the technology. But said capacity has spawned access to ontologies and histories that have always been there, evolving right along with and in conversation with the dominant narratives. Ignorance is now an even more brittle excuse, and Solarpunk (along with the rest of us) is engaged in the messy, brutal process of adaptation. The 2021 solarpunk anthology published by World Weaver Press, Multispecies Cities, has Futures as part of its subtitle. Emphasis on the pluralism of futures seems to be the focus of many stories. The elements of a solarpunk worldview are potentially intersectional with indigenous socialism, African collectivism, and Afrofuturism among many others. There is great power in this multiplicity. But multiplicity requires negotiation. It remains to be seen exactly what comes of this process and what networks of solidarity will be most effective in articulating Solarpunk imaginaries to a broader audience, which ultimately, should be the goal.

In a National Science Teaching Association guest editorial “Exploring Climate Justice Learning: Visions, Challenges, and Opportunities,” Deb L. Morrison and Philip Bell write (and link to many resources that are particularly cogent for education):

As climate change education efforts progress, there is a need to entwine such work with the principles of climate justice named by those most impacted and having worked at the intersections of climate change and justice longest. Intersectional issues of justice need to be fundamentally part of climate science education and climate change learning. To support this, we must find ways to support our educators to engage in social, economic, political, design, and historical dimensions of this work. To this end we need to consider questions such as:

- Who defines what climate justice learning goals and approaches should be?

- Whose knowledge of climate science is being named and engaged in instruction? By whom? Toward what ends? Under what forms of consent and collaboration?

- What is the role of science education in dismantling, desettling, and reforming educational systems to focus on climate justice?

- How can we disrupt white environmental imaginaries within curricula and instruction about how we collectively respond to climate change and instead focus on just and thriving futures for Communities of Color?

- How do we connect science and STEM instruction to collective action, activism, civic participation, and social responsibility?

- How do privileged teachers engage in this work with respect, humility, and authenticity?

Facilitating Paths to Solarpunk Futures

Colleagues, friends, and allies, perhaps you already sense why solarpunk offers so much for education, especially ESE and Education for Sustainability (EfS), even with flaws regarding inclusion and representation. I propose that facilitating paths to solarpunk futures be our overarching mission in the field. After all, we want to generate hope and action towards a just, regenerative future. We want to spin many ideas and paths for getting us to such a future. We in education might also be positioned to bring in more voices to diversify solarpunk.

Sarena Ulibarri offers:

One of the limitations of self-proclaimed “climate fiction,” whether solarpunk or not, is that it tends to attract a self-selecting audience. Someone who is a climate denier is highly unlikely to pick up a climate fiction book in the first place, much less change their mind because of it. For me, it’s less about promoting a specific agenda or set of solutions, and more about adjusting people’s worldview through an emotionally-resonant human-scale story. If we can shift the paradigm of how people think about climate change, we can shift the possibilities of what the future can look like, and the solutions will follow.

My hope in writing this article is that the notion of solarpunk reaches beyond those already involved with solarpunk, that we writers are not only writing for a solarpunk audience, but reaching the wider mainstream. That is how we change the world.

An aside: I used to think the name of our Center for Sustainable Futures (CSF) should be singular, not plural futures. However, now that I’m immersed in solarpunk, I’m happy that we say Futures. Perhaps Center for Solarpunk Futures would be a more potent name and would keep our acronym CSF (I note in jest to my colleagues).

Justine Norton-Kertson says:

Solarpunk isn’t just literature, art, and counterculture aesthetics. It would still be valuable if it was. However, solarpunk is also real projects, communities, problem solving, and worldbuilding taking place right here in the real-world present. It’s a worldview and way of living that exists right now. It’s particularly relevant to the current global, historical moment and context, and it has the potential to be a powerful force for social change.

A growing number of academicians and education researchers are working in a solarpunk way. For example, my colleague Antti Rajala at the University of Helsinki in Finland is involved in a project, Pedagogy of concrete utopias: Fostering youth agency and climate activism in formal education. The project centers youth who have new solutions and ideas for ecologically sustainable ways of organizing life and activity. From the project abstract:

Education cannot any longer emphasize enculturation into existing culture that have shown to be unsustainable. There is a need for new ways of living, thinking and consuming. The project examines a novel pedagogical concept of concrete utopia that helps to advance understanding of the practical relationship between climate change on the one hand and human communities and culture on the other hand. The project creates new kind of dialogue between youth, teachers, policy and decision makers, NGOs and other social actors. Thus, the project creates new ways in which actors from different disciplines and layers of society can collaborate.

“Utopian” literature is entering the curricula as a way to think critically about our reality and spur environmental action. If you are engaged in such an endeavor, I hope the literature you work with is solarpunk more than standard fare utopian. Hannah A. Barton (she/they), postgraduate Fantasy scholar from the University of Glasgow, is among a growing number of scholars studying climate imaginaries. She shares:

The specifics of speculative energy imaginaries (solarpunk, cyberpunk, dieselpunk, etc) have a lot of educational value . . . speculative works can teach us what futures might be and that change can be possible. . . . Solarpunk worlds leave doors open for our present to be reconsidered and provide literary teachings that can alter imaginations of current and future readers.

Solarpunk Resources

Above, Meira Datiya mentions the dystopian state of the world that includes white supremacy, fascism, colonialism, and uber-capitalism. She adds: “That being said, there's so much to be inspired by right now and I want to share a shortlist with you of some current projects around the world that are actively working towards bringing a solarpunk future into being.”

Ecodemia | An online diploma course from the UK, that teaches students about regenerative landscapes, permaculture, de-urban design, humanitarian design, & bio-design. ecodemia.org.uk

Indigenous Friends | Indigenous traditional teaching & coding program. indigenousfriends.org

Precious Plastic | preciousplastic.com

Institute for Social Ecology | social-ecology.org

The Phylo(Mon) Project | A DIY card game to teach kids about biodiversity. phylogame.org

Symbiosis | Dual power, municipal movement. symbiosis-revolution.org

Remembrance Day for Lost Species | lostspeciesday.org

Dark Mountain Literary Journal | dark-mountain.net

Food Not Lawns | foodnotlawns.com

“It's going to take a lot of work to make it a reality but every time someone creates a piece of art, tells a story, goes to a protest, or plants a garden for their community, we are taking steps towards that brighter future for all of us.”

Justine Norton-Kertson offers:

Solarpunk’s focus on the climate crisis and climate solutions is an important part of what makes it such an important genre and counterculture. Climate change is a serious problem right now in the present. Solarpunk then has a connection to the present and to the real world that other science fiction and fantasy genres don’t. People who could be called Solarpunks are attempting to build the utopian world that we envision in our speculative fiction. They are out in the contemporary world right now building intentional and prefigurative communities, and creating and implementing solutions to the climate crisis. Solarpunks are protesting the lack of action coming out of UN Climate Change Conferences, and are engaging in direct action in the struggle against fossil fuel empires. The result of the union of present and future, combined with an analysis of the past rooted in the goal of building a more equitable and just world, Solarpunk has the potential to impact the real world and the development of our societies in a way that other science fiction and fantasy genres generally don’t aspire to.

I hope you feel inspired by the many people creating collaborative, regenerative communities and projects. Some other examples:

Earth Activist Trainings, founded and facilitated by Starhawk and friends, have created a growing community of EAT activists who are seeding permaculture and regenerative projects around the world.

Solarpunk Portland envisions regenerative projects to meet Portland, Oregon (US) needs. As Justine says, these provide a blueprint for how to start transforming a major U.S. city into a “solarpunk city.”

Climaginaries is a multidisciplinary group of faculty from European universities exploring a path towards a post-fossil world.

Work in the real world for justice and a regenerative future need not carry the solarpunk moniker. Indeed, that label might be colonizing and insulting to Indigenous groups who have always had the knowledge and tools for right relationship with the Earth that not only sustains all living beings and the health of ecosystems, but is inherently regenerative. Some examples:

Hattie Carthan Urban Farm and Market is a grassroots, people of color-led agricultural revitalization project in Central Brooklyn NYC (US). They increase access to locally grown fresh food, farm culture and intergenerational agricultural education in a neighborhood classified as a “fresh food desert." They include community-based cultural programs and ventures which nourish human potential and cooperative economics. My dear friend Yonette Fleming is a founder and core to this project. They do wonderful work.

National Black Food & Justice Alliance “represents hundreds of Black urban and rural farmers, organizers, and land stewards based nationwide [US] working together towards an intergenerational, urban/rural movement . . . Together, we are designing, building and protecting the nourishing, safe and liberatory spaces our communities need and absolutely deserve.” Peruse the many member organizations for a wide view of the movement.

NDN Collective is “an Indigenous-led organization dedicated to building Indigenous power. Through organizing, activism, philanthropy, grantmaking, capacity-building and narrative change, we are creating sustainable solutions on Indigenous terms.”

Native Food Alliance advocates for and supports “all levels of food security and food sovereignty in local, tribal, regional, national and international arenas.” They are home to the Indigenous Seed Keepers Network.

The Cultural Conservancy is a Native-led organization “to protect and restore Indigenous cultures, empowering them in the direct application of traditional knowledge and practices on their ancestral lands.”

Indigenous Environmental Network founded by Indigenous peoples to address environmental and economic justice. They help build the capacity of Indigenous communities and tribal governments to develop mechanisms to protect sacred sites, land, water, air, natural resources, health of their people and all living things, and to build economically sustainable communities.

Justine adds these examples of antiracist and decolonial projects:

Municipal Eco-Resiliency Project is a food sovereignty project in Portland, Oregon being organized by an Indigenous activist.

The growth of urban farming in Detroit’s black communities creates regenerative culture and food security.

While I have researched the resources I list to some extent, I have personal knowledge of and relationship with only a few of the projects. Some may accept corporate sponsorship or have other parameters that could be considered at odds with solarpunk. Still, the core work of these projects lean towards solarpunk values.

Each of the generous people who sent their thoughts for this article (thank you!) are contributing to Solarpunk futures, particularly through writing and publishing. In addition to the aforementioned Solarpunk Magazine, Optopia Zine, and World Weaver Press, here are more literary resources:

Stelliform Press is an independent Canadian publisher focusing on speculative and literary fiction and creative non-fiction which takes up the conversation around the climate emergency and an intersectional view of environmental justice.

Reckoning is a nonprofit, annual journal of creative writing on environmental justice

Subscribe to my CliFi list on twitter to peruse solarpunk and climate fiction info, including the feeds of many of the people who contributed to this article. I welcome you to follow me @brtflame, as well.

Grist/Fix Imagine 2200: Climate Fiction for Future Ancestors is a story contest to envision the next 180 years of equitable climate progress. The stories “create intersectional worlds in which no community is left behind. Whether built on abundance or adaptation, reform or a new understanding of survival, these stories provide flickers of hope, even joy, and serve as a springboard for exploring how fiction can help create a better reality.”

Dragonfly.eco brings awareness of fiction authors around the world exploring a variety of environmental and nature subjects in their stories. Mary Woodbury says of her site, “I want to emphasize around the world because most media focuses on a subset or local region of such authors and books, and my site explores how this fiction looks in different areas and among authors with varying degrees of cultural experience, privilege, and so forth. I think a wider angle is important in order to understand a broad perspective about things like climate change, which isn't what we see when we're looking out our own personal windows but what we can learn from others who perhaps may be subjected to much harsher realities. It's like putting a world literature puzzle together and seeing the forest as well as giving dignity to local places and seeing more of the individual trees.” Searching “solarpunk” on the site will yield, among other things, a category in the database, an interview with Adam Flynn, a link to a solarpunk chat at SFFWorld.com, and a contest Mary held a few years ago.

Rewilding Our Stories is the discord server Mary Woodbury founded for collaboration and interaction. While mostly used by eco-lit writers and rich with writing resources, there are solarpunk and academics channels.

Many thanks to Carly A-F and Elijah Johnson for granting permission to use their solarpunk art in this piece. Elijah is the winner of Yishan Wong’s 2021 solarpunk art contest and Carly is a top ten finalist.

Will you work towards solarpunk futures? I welcome your musings and sharings related to this article. Perhaps a part 2 will form from your stories. Remember, solarpunk is ever evolving. It’s a container with wide and permeable periphery and can hold as much as we create together.