Building Bridges

Strangers don't always expect an icon of the civil rights movement to have a playful sense of humor, so it's a bit disarming when Ruby Bridges Hall uses hers to charm an audience. "Most of the time, kids expect me to be six years old, and grown-ups expect Rosa Parks," Bridges told a packed Horace Mann Auditorium, adding that she fell somewhere in between. "People are surprised to learn I have a sense of humor," Bridges said earlier. "When people talk about racism, everybody is very tense. Anyone that makes it more lighthearted eases people up a bit." At 50, the youthful Bridges also projects the virtues one might expect-the same calm, quiet dignity that helped break down racial barriers in the segregated south of the 1960s.

Today, she continues to follow her calling, devoting her life to promoting racial harmony among America's schoolchildren

A Trailblazer's Story

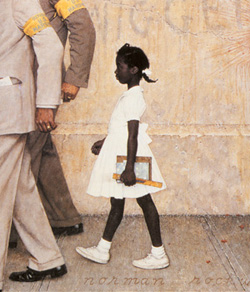

Bridges is remembered as the model for the African-American girl in the starched white dress, beginning her first day of school escorted by federal marshals, in Norman Rockwell's 1964 painting "The Problem We All Live With."

In 1960, at age 6, the child who inspired that painting endured the daunting experience of being the first black student to integrate the all-white William Frantz Elementary School in urban New Orleans.

For all of that school year, Bridges was almost the only child in attendance, white parents having pulled their children from the school. Each day for many months, she walked through a mob of angry protesters to spend her day alone in a classroom with Barbara Henry, a Boston transplant and the only teacher willing to instruct her.

Bridges handled this onslaught with amazing poise, even stopping to pray for the protesters as she entered the school.

Naïveté helped shield her as well. The six-year-old initially mistook the barricades, hateful signs, police officers patrolling the streets, and angry protesters throwing objects as part of a New Orleans tradition: "Mardi Gras."

"I felt as though I were in the midst of a parade," she remembers. "Later on, the [true] situation came together for me when I came in contact with a few of the other kids. The principal would separate us."

After her difficult first year, the mobs disbanded and the white students returned to William Frantz. While racial tensions continued through her high school years, as New Orleans' schools integrated grade-by-grade, the focus on Ruby subsided.

A Public Figure Again

For many years, Bridges lived quietly. After high school, she studied travel and tourism and spent many years as a travel agent, using the opportunities her profession offered to see much of the world, from Europe to Singapore. She also married and began raising four children, the youngest of whom is now 12.

In 1995, Bridges returned to the spotlight, as the subject of a groundbreaking children's book, The Ruby Bridges Story. Written by Robert Coles-a psychiatrist who studied the young Bridges as she faced the challenges of her first grade ordeal-the illustrated book told the story of Ruby's first year at William Frantz.

"It was the first book of its kind to try to explain racism to a five- or six-year-old," she said. "I spent six months promoting it."

Bridges also worked with Disney to develop 1998's Ruby Bridges, a well-received movie for television. "I'm very proud of that film," she says, explaining that the creators-who included Euzhan Palcy, one of Hollywood's few black female filmmakers-worked hard to accurately recreate her experiences as a young girl in the racially divided New Orleans of the early 1960s.

"The writers met with a number of people, including Dr. Coles, my mother and Barbara Henry," she said. "The cast and crew came together to do a piece of work we were proud of."

In 1999, Bridges wrote "Through My Eyes," a personal account of her unusual first grade experience. Asked if she'd consider writing a longer memoir, Bridges confessed she'd given the idea some thought, but added, "I feel there's still so much to be done. If I wrote them now I would need to write another one (later)."

A Renewed Commitment to Integration

In the early 1990s, Bridges began refocusing her time and energy on the subjects of children, racism and integration, when she returned to William Frantz as a volunteer.

In 1999, her concern led to the creation of Ruby's Bridges, a foundation now working to have her first school designated a national monument, a move which would help bring much-needed funding to this inner-city school.

Today, William Frantz is segregated again, but now its entire student body is African-American. Bridges' goal, she explains, is to convert this under-funded and physically decaying institution into a model school, one children of all races would want to attend.

Ruby's Bridges also is partnering with the Simon Wiesenthal Center, which has helped the foundation launch eight school partnerships in Los Angeles. This program links inner-city and suburban schools, offering children from different backgrounds a chance to spend time on each others' campuses, collaborate on volunteer projects and build greater understanding. Bridges is gradually expanding this program nationwide.

A Voice for Harmony

Bridges spends many of her weekdays traveling, speaking to school groups-especially young children-about her experience and the topic of racism. "Getting past racial differences will come through our children. The majority of my time now is spent going to schools and sharing my story with kids. I try to help them understand that racism doesn't have any place in our hearts or in our minds."

Bridges remains optimistic and strong in her belief that school diversity is one key to wiping out racism. And she does see change. "It bothers me when I hear that integration failed," she said. "As far as I'm concerned, my efforts didn't fail."

Published Thursday, Jan. 13, 2005