What Really Works When It Comes To Closing The Achievement Gap?

At a time when there is an increasingly sharp divide between the nation's "haves" and "have nots", the odds would seem against three-and-a-half-year-old Melanie Sandoval ever being one of the "haves."

Born to Guatemalan immigrants whose combined incomes are below the federal poverty line, Melanie lives in a tough neighborhood on the west side of Stamford, Connecticut. Since summer of 2006, when her mother had twins and stopped working as a nanny, the family's finances have been tighter still.

Still, Melanie's parents are bright, caring people who have stayed together and worked hard. Melanie also attends the Childcare Learning Centers' Stillwater Head Start Center, just five minutes' walk from her house, which leaves her mother, Marlen, with more time and energy for the twins. The center follows the Creative Curriculum for Early Childhood, which includes more than 30 specific targets for children's social, emotional, cognitive and physical development. Melanie's head teacher, Lisa Barnes, has 10 years of classroom experience, and the assistant, Haydee Maestre, is bilingual.

"She loves her teachers, they're amazing," Marlen Sandoval says of her daughter. "On vacation, she says, -'I want to go to school.' Before she was there, she wasn't talking clearly. Now she's speaking more, she knows colors, numbers. There's been a lot of change. She's more friendly, she plays more. It's amazing."

In fact, the most recent national survey of Head Start-'"a program offered free to impoverished families and students with special needs-'"found that while children typically enter with below-average skills, they make significant gains in vocabulary and early skills in math and writing. Latino children like Melanie also make significant gains in both English and Spanish vocabulary. A 2000 RAND study found that, for whites, participation in Head Start is associated with a significantly increased probability of completing high school and attending college, as well as elevated earnings in one's early 20s, while there was "suggestive evidence" that African American males who attended Head Start were more likely than their siblings to have completed high school.

For families like the Sandovals, then, Stillwater would seem to be a godsend-'"but what's in it for those who foot the bill? After all, a year's education at the school, which offers an onsite nurse, two daily meals and a snack, a teacher-to-student ratio of two to 17, and visits by a family social worker, costs the state of Connecticut between $12,000 and $15,000 per child. In all, the U.S. spends more than $7 billion on Head Start, which encompasses some 19,000 centers and roughly one million students.

This past winter, a new study led by TC education economist Henry Levin provided perhaps the most compelling evidence yet that this investment pays big dividends - not just in improved lives and life chances for Head Start students and their families, but in hard dollars for the American taxpayer.

Levin and colleagues from Princeton, Columbia and the City University of New York focused on a group of strategies that have been proven to boost high school graduation rates, including not only quality preschool, but also smaller-size classes in grades K-3, increased teacher salaries across all grades, and intensive small high schools with student and family supports. As a measure of educational effectiveness, they calculated the number of additional graduates each strategy generates per 100 students. They toted up the "public gift" conferred by each new graduate in increased taxes paid, reduced crime and likelihood of incarceration, reduced use of the public health care system, and reduced dependence on public assistance. Finally, they deducted the implementation costs of each graduation-boosting strategy, including the expenses that result from students' increased years of schooling.

The bottom line: use of these proven strategies could save the U.S. taxpayer a net of $127,000 for each new graduate they generate-'"the equivalent of $45 billion annually if the number of high school dropouts nationally among 20-year-olds were cut in half, and $18 billion if they were reduced by one-fifth. For young black males, the student population most at risk for dropping out, the figure is even higher. The net public savings for each new graduate added among this group is estimated at $166,500.

Those figures do not even include the private benefits of improved economic well-being that would accrue to the new graduates themselves.

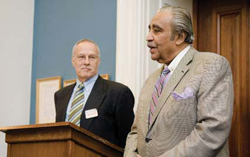

"What this study is really saying is that, beyond the compelling moral reasons for helping disadvantaged children make it through high school, there are economic reasons as well," Levin, who is TC's William Heard Kilpatrick Professor of Economics and Education, said at a Congressional briefing in spring 2007 that was hosted by Congressman Charles Rangel. "Providing greater equity for all young adults would also produce greater efficiency in the use of public resources. So this is a case where America truly can do well by doing good."

In 2006, Congress cut Head Start spending nationally by one percent. The program's formal status has been uncertain for several years, as its administrators have sought without success to win federal reauthorization. Armed with a growing trove of data like the Levin study, they're hopeful for a better outcome.

So are Melanie Sandoval and her family.

Published Wednesday, May. 9, 2007