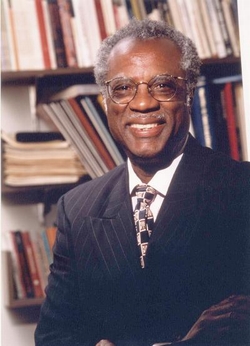

Tisch Lecture: James A. Banks

One Country,

Many Cultures

Tisch

lecturer James Banks talks about

educating for citizenship in a diverse world

In a world increasingly characterized by immigration, globalization and ethnic nationalism, is a multicultural approach to citizenship healing or divisive?

For James A. Banks, who delivered TC's annual Tisch lecture in late September, the answer is clear: there's unity in diversity. In a talk titled "Diversity and Citizenship Education in Global Times," Banks -- the Kerry and Linda Killinger Professor of Diversity Studies and Director of the Center for Multicultural Education at the University of Washington -- attacked traditional methods of citizenship education and advocated an alternative, multicultural approach that he believes would promote tolerance and social justice. Along the way, he took his Milbank Chapel audience through a recap of several centuries' worth of thinking about citizenship.

Certainly there are few people who can speak more authoritatively on the subject. Banks, who is African American, is considered one of the founders of the multicultural education field, and his books -- including Diversity and Citizenship Education: Global Perspectives, which examines the tension between a unified political culture and a racially and ethnically diverse society in 12 nations -- have had a powerful influence in public schools, colleges and universities worldwide. He also is the editor a series on multiculturalism for the Teachers College Press and is currently editing The Routledge International Companion to Multicultural Education, which includes chapters by authors from around the world.

Still, in his talk, Banks portrayed his thinking as still running counter to what he termed the prevailing "liberal, assimilationist" model of citizenship education, which he argued requires people to give up their distinctive cultural identities in order to fully participate in civil society. Educational materials geared to this model help to marginalize and stereotype ethnic minorities, he said, recalling the image of the "happy slave" that he encountered in textbooks during his own elementary school years in Arkansas in the 1950s.

"The only black folks in textbooks were slaves," said Dr. Banks. "And they were always happy."

Banks also criticized what he called "liberal assumptions" that individual rights trump group rights, and that racial and ethnic affiliations are necessarily divisive. Drawing on the work of contemporary thinkers like the American anthropologist Renato Rosaldo and the Canadian political philosopher Will Kymlicka, he argued that minority groups instead enrich the dominant or mainstream culture.

Describing the work of the British sociologist T.H. Marshall, who first expanded the notion of citizenship to include social rights as well as civil and political ones, Banks suggested adding cultural rights to that list, too. And he said that group action by minorities can advance individual rights and promote equality. By way of example, he credited the civil rights movement of the 1960s with his own appointment as one of the first black educators at the University of Washington in 1969. "That never would have happened without the Civil Rights movement," he said.

Banks also emphasized that the problem of inculcating shared national values without marginalizing minority groups is not just an American one. He cited recent controversies in Europe over the education of immigrant children, as well as the fracturing of civil society in Iraq along sectarian lines.

Finally, Banks addressed the implications of a multicultural view of citizenship for curricular reform. The principal goal of multicultural citizenship education is to help students balance their various cultural, regional, national and global identities, he said -- but a truly transformative approach to citizenship education would also give students the knowledge, skills and values to challenge inequality throughout the world and to create just and democratic multicultural societies.

Rather than simply requiring students to memorize facts about their form of government or encouraging non-reflective loyalty to their countries, transformative citizenship education would demand that both teachers and students learn to recognize and fight racism, Banks said. It also would require teaching materials that preserve diverse ethnic and cultural perspectives and ensure that students from different cultural, ethnic and social groups enjoy equal status in the classroom.

Published Tuesday, Oct. 2, 2007