Teaching--and Debating--the Lessons of Katrina

In September, TC marked the launch of a 100-page teaching tool developed by its faculty, students, staff and alumni to be deployed in conjunction with director Spike Lee's four-hour HBO documentary, "When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts."

In September, TC marked the launch of a 100-page teaching tool developed by its faculty, students, staff and alumni to be deployed in conjunction with director Spike Lee’s four-hour HBO documentary, “When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts.”

The curriculum—“Teaching The Levees: A Curriculum for Democratic Dialogue and Civic Engagement”—was developed with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation in conjunction with HBO. It was published by TC Press and has been distributed free of charge to 30,000 teachers nationwide, together with DVDs of the film.

The curriculum—“Teaching The Levees: A Curriculum for Democratic Dialogue and Civic Engagement”—was developed with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation in conjunction with HBO. It was published by TC Press and has been distributed free of charge to 30,000 teachers nationwide, together with DVDs of the film.

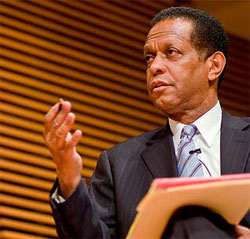

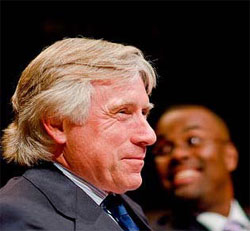

The launch event, held in TC’s Cowin Conference Center, was attended by more than 600 people and included remarks by TC President Susan Fuhrman, New York City Public Schools Deputy Chancellor (and TC alumna) Marcia Lyles and TC faculty member Margaret Crocco, who led development of the curriculum. But the heart of the proceedings was a spirited debate by a panel made up of New Orleans City Councilwoman Cynthia Hedge-Morrell, the University of Wisconsin’s Gloria Ladson-Billings, Princeton University’s Eddie Glaude, Jr., and Columbia University President Lee Bollinger. Their discussion was moderated by New York Times columnist Bob Herbert, who started things off by asking, “Have we learned anything from the Katrina experience? And are you optimistic or pessimistic as a result?”

Hedge-Morrell, whose district includes New Orleans’ heavily damaged Ninth Ward, said one painful lesson for her has been how “the media instantly made the victims the problem.” On the bright side, she said, “I continue to see that the American people are unbelievable. We’ve had such an influx of citizens—people taking off from their jobs, people on break from college, people spending a year of their life—to help rebuild.”

Ladson-Billings’ answer to Herbert’s question was “The jury is out.

Ladson-Billings’ answer to Herbert’s question was “The jury is out.

“I tell my students to see me as neither optimistic nor pessimistic, but as pissimistic, because I’m so pissed off,” she said, drawing a laugh. “We live in a country where some people matter more than others, even in death.”

Glaude said Katrina has given fodder to people with diametrically opposed views of government: those who believe that the failure of the national, state and local governments to deliver services in the wake of Katrina shows that bureaucracy should be decreased and those who believe that governments at all levels have been gradually weakening for many years as a result of the systematic dismantling of the New Deal.

Glaude said Katrina has given fodder to people with diametrically opposed views of government: those who believe that the failure of the national, state and local governments to deliver services in the wake of Katrina shows that bureaucracy should be decreased and those who believe that governments at all levels have been gradually weakening for many years as a result of the systematic dismantling of the New Deal.

“For me, I keep going back to my man James Baldwin, because throughout all of this we keep encountering American innocence,” Glaude says. “People say, ‘I didn’t know there were all these poor people in this country.’ Well—really?”

Bollinger said that the Katrina experience has confirmed for him that “we’ve lost a sense of national purpose, a mission or will to deal with issues of race, class and inner-city deprivation.” And Ladson-Billings echoed that disappointment as the discussion wound down.

“I’m old enough to remember a time when the word ‘public’ was not pejorative,” she said. “I got my public polio vaccine. People in my family moved into public housing that was safe, reliable and affordable, to get away from unscrupulous private landlords. And if you wanted to move forward in society, you went to public schools. Now we all want to live in private, gated communities. Consumerism prevents us from seeing ourselves as public citizens. You might remember that after 9/11, our head of state urged us to go out and shop. Well, I say, ‘Don’t reduce me to a consumer. What can I do to really help people?’”

Published Tuesday, Apr. 1, 2008