Aging Artfully: The tale of a TC study of aging artists in New York City and four of its subjects

New York City is a place where being an artist can seem as regular a job as any of the City's more prosaic employments-'"but without the security so-called real world employment offers. As a result artists generally find themselves having to invent their own form of retirement.

And that, argues Joan Jeffri, Director of TC's Graduate Program in Arts Administration, is not necessarily a bad thing. Armed with creativity and devotion to their craft, artists are remarkably good at adapting as they age. Even if they're not so good at the practical stuff-'"setting up wills or passing on their spaces-'"they tend to stay active and plugged into networks of friends and colleagues. Even more important, they continue to hope and dream.

Jeffri has made her mark documenting the ways in which artists cope. In her new study, "Above Ground," she surveyed 213 visual artists ages 62 to 97 across New York City's five boroughs and set out to document the survival skills and social supports of aging artists in the City. The result is both a blueprint for how to preserve this hardy breed, which faces the threat of extinction from the City's relentless gentrification and booming real estate prices, and a primer for society in general on successful aging. The title is drawn from the words of the study's oldest participant who, when asked, "How are you doing today?" replied, "Well, I'm above ground."

In the following stories, meet Jeffri and four artists who participated in her study: Hank Virgona, Hanna Eshel, Betty Blayton and David Yuan.

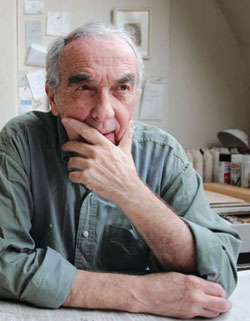

Hank Virgona

Chatting with Hank Virgona about New York galleries in the '60s, artists he knew (such as Joseph Solman) and his gleeful baiting of Henry Kissinger's office assistants, it's hard to believe his claim that he became an illustrator because he didn't want to talk to people. Virgona was fresh out of the army, he says, a young man with a bad stutter for whom art seemed an escape from social awkwardness.

"Of course," he says smiling, "I didn't realize I'd have to talk to the models."

But somewhere along the way, the shy young man arrived. His commercial illustrations appeared in such glossy magazines as Fortune and Harper's and on the opinion page of the New York Times. Soon he channeled his energy into art ranging from political satire to still lifes to more abstract explorations of textures. He has since staged more than 30 one-man exhibitions, has won a slew of awards, and his work is included in a number of prestigious collections, including at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Today, Virgona still works in the same Union Square studio he first rented for $35 a month nearly 50 years ago. Working in the same place for so long-'"when Virgona turned 68, he "slowed down" by coming in only five and a half days a week instead of six-'"has provided him with conversation as well as comforting routine. And, his long-ago shyness notwithstanding, he clearly likes to talk-'"especially about art. As he leafs through his portfolio, a letter from George Stephanopoulos, ordering several of Virgona's prints for the Clinton White House, falls out. Virgona smiles: "I like to put that there and pretend I'm surprised to see it."

It wasn't the first time he'd had interest from the White House. During the Nixon era, he sent several satirical pieces to Henry Kissinger and, to his surprise, kept getting notes back from the office about how much they loved the work.

Hanna Eshel

With a narrow hallway entrance that widens out into a giant former factory, Hanna Eshel's NoHo loft seems bigger on the inside than the outside, like the wardrobe to Narnia or Dr. Who's police box.

Eshel needs the space. A sculptor who, until recently, worked primarily with marble; she's storing some 20,000 pounds of her creations.

Perhaps not surprisingly for someone who's spent thousands of hours chiseling and polishing marble, Eshel's highest compliment for a work of art seems to be, "It's so strong." The Pyramids at Giza, Stonehenge, thick tree trunks around the temples of Cambodia-'"all were "strong" enough to influence Eshel's art. But what really piques her interest now is the energy the world holds. At 81, finding marble too physically demanding a medium, she spends her time painting around the edges of photographs she's taken: for example, she added to pictures of Cambodian trees by extending the roots and branches into something half-plant,

half-electricity.

Eshel grew up in Israel and served in the Israeli Army at age 14. She traveled to France to paint and study classical art, but after developing an interest in sculpture, found herself in Carrara, Italy, where she first encountered marble. What she had intended to be a short visit turned into a six-year stay.

Thirty years ago, she helped convert her loft from a factory to an artist's space, and she's been living here ever since. "New York is great for seniors," she says. "People leave you to do your own thing if you want, and you can be yourself."

Betty Blayton

Betty Blayton has created images for as long as she can remember. From her beginnings-'"surreptitiously illustrating the walls of her parents' stairway and her first solo show in 1966-'"she has steadily shown work in painting and sculpture, impressing critics at the New York Times, among others, and getting her work included in the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Yet for Blayton, art is more than exhibitions; it's a way to center herself ("You need to get rid of all the monkey noise of the world," she says) and to help answer metaphysical questions that she's pondered for decades. Many of her pieces show bright colors and disparate geometry, depicting emotions taking on material form or souls moving between lives.

"I've been here before," she says. "I firmly believe that. My life has been one big evolution, and it doesn't stop there."

Nevertheless, she says she stumbled into the work that she's most proud of-'"helping to found a series of artistic outlets for kids in Harlem, beginning at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1965.

Blayton had been teaching students through funding provided by President Johnson's anti-poverty initiatives and soon met Frank Donnelly, a member of the Junior Council at the Museum of Modern Art. Her students had been complaining that there was no organized place in Harlem to see fine art, so Donnelly and Blayton convinced some wealthy backers to fund the Studio's creation.

Her work in Harlem grew from there, as she helped to found the Children's Art Carnival in 1986 and the Harlem Textile Works in 1983, providing art education to young children and jobs to teenagers that would teach them all aspects of the fabric design industry. She retired from the Carnival in 2004 at the age of 67, but these days she's busier than ever. "I retired without a pension," she says. "I need to eat and pay the mortgage, so now I have to concentrate on selling."

David Yuan

For David Yuan, calligraphy is life-'"not a narrow obsession but a medium for understanding the world. To truly excel in calligraphy, he says, is to pursue the Tao, the order of the universe. Achievement depends not just on countless hours practicing strokes and perfecting form, but also on a deep understanding of Chinese culture and history.

"It's hard to even translate many of the central concepts," he says. "Love is the most important thing, not in a specific Christian or Buddhist sense, but simply to respect life."

Practice, of course, is exceedingly important. "It's still a technique," he says. "You need to express the strokes, the dots, to keep the rhythm of the piece." But each style is a celebration of and reaction to culture. Yuan's work reaches back 1,200 years for its primary influence, the T'ang Dynasty. "A lot of calligraphy today is more like Chinese artwork," he says, "beautiful in its own way, but I enjoy the brightness and clarity of the T'ang work. It's the best."

Yuan's work has received considerable recognition and is included in collections in the national museums of China and Taiwan, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Princeton University, among others. He's proud to show the strength of classical-style art, and he's glad that it has been commercially, as well as critically, successful. "Money is always stress, no matter what you do, but it makes you push yourself to improve your standards."

Yuan is active in galleries in Flushing, Queens, which has many Chinese immigrants and artists. There, he says, being an artist is as much about being part of an active community as it is about showing work. "Artists of all backgrounds come in to talk. You have to exchange knowledge to learn new directions to go in."

This community keeps him going even as he practices an ancient art in a modern era: "In the ninth century, people would practice all day for a lifetime. Now we compete with TV, computers, e-mails. It's an -'e-era.'" z

The Artist as Model

Joan Jeffri has lived the lessons of her study

"Artists don't retire," says Joan Jeffri. They simply keep reinventing themselves.

Certainly reinvention has been a theme in Jeffri's own life. Prior to her academic career, she was both a poet who was a protg of blacklisted writer Louis Untermeyer and an actress good enough to appear in the national tour of Harold Pinter's "The Homecoming" and with the Lincoln Center Repertory Company.

"My agent wasn't very good, so I started negotiating my own contracts," she says. "I realized somebody needed to champion the artists' side of things-'"that artists were busy making their art and that this was something I did fairly well."

In 1975, Jeffri was hired to create programs at the School of the Arts at Columbia and shortly afterward developed the university's first course in arts administration. She then left to have her first child-'"but when he was just six weeks old, Columbia called to say that 65 people had registered for the course, and there was no instructor. Would Jeffri be interested in teaching it?

She was, and she did. And what has followed, over the years, is a unique career dedicated to understanding how artists work, live, age and survive in a modern capitalist economy-'"and what lessons their experiences hold for society in general.

Jeffri has worn many hats in pursuing that singular focus. She is a leading commentator on the economics of the American art market, which she has described as "a small incestuous family, inaccessible to the general public and kept active by groups of tightly connected insiders." She has written widely on the management of arts organizations and has also served as President of the Association of Arts Administration Educators, President of the Board of the International Arts-Medicine Association and on a national task force for health care and insurance issues for artists.

But her signature contribution has been her studies of working artists, conducted through the Research Center for Arts and Culture, which she founded at the School of the Arts and moved to TC in 1998. These include "Changing the Beat," on jazz musicians in New York, New Orleans, San Francisco and Detroit; "Making Changes," on professional dancers in 11 nations; and now "Above Ground."

Contrary to the stereotype, Jeffri has found that artists are not typically depressed or suicidal and are, in fact, a better bet than most to stay out of nursing homes.

"Older artists have a great deal to offer us as a model for society," she says, "especially as the workforce changes to accommodate multiple careers and as baby boomers enter the retirement generation."

Published Wednesday, Mar. 26, 2008