When Giants Depart

One held court in her apartment, inspiring young and old until just weeks before her death at age 96. The other held court in TC’s hallways, invariably suggesting, as a close friend recalls, “We should have a real meeting soon.” Regardless of where one encountered them, Maxine Green and George Bond were points of reference for generations at Teachers College and beyond.

By: Joe Levine

Putting Africa On The Map of History

George Bond was an old fashioned “dirt anthropologist” who brought the world Africa’s story through the voices of Africans themselves.

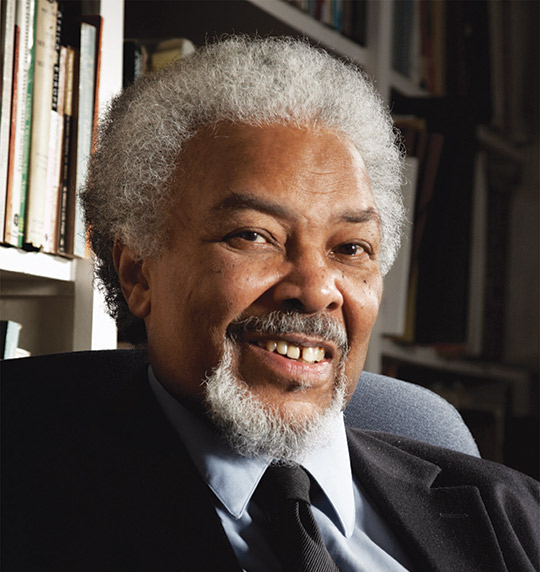

I have sought to represent the voices of Africans as they contributed to the making of their own history.” George Clement Bond, who died in May at age 77, was the grandson of a former slave who attended Oberlin College. He helped transform the field of anthropology by engaging one of the most profound questions of our times: the place of non-Western, non-white races in the narrative of human civilization.

Bond, TC’s William F. Russell Professor of Anthropology and Education, pitted himself against a prevailing colonialist view that, in the words of the British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, “There is only the history of Europeans in Africa. The rest is darkness.” Bond’s work shone new light not only on Africa, but his own field as well.

“In the 1960s and 1970s, George, particularly as an African American, was a key actor in asking, ‘What does it mean to be a anthropologist, when anthropology is so linked to the colonial project, when it, itself, has been a colonizing intervention?’” says Mamadou Diouf, the Leitner Family Professor of African Studies at Columbia University, who collaborated with Bond on projects in southern Africa “Others among his cohorts had begun calling themselves sociologists, to distance themselves from these associations, but George chose to work from within the discipline and reframe it.”

Bond was a self-described eclectic who drew on Marxist theory, structural functionalism, the work of Antonio Gramsci and others who look at the cultural mechanisms that perpetuate power and the broad vision of education advanced by historian and TC President (1974–1984) Lawrence Cremin, who hired him. Yet Bond patterned himself perhaps most after classical social anthropologists, such as Elizabeth Colson, who taught him during his undergraduate years at Boston University, and Lucy Mair, his mentor at the University of London. He spent years in remote African villages, documenting indigenous historical narratives and their use by an emerging class of tribal intellectual and political leaders, whom he called elites.

“George was an Africanist, a term used when anthropologists were labeled by the world regions that they studied,” says Lambros Comitas, TC’s Gardner Cowles Professor of Anthropology and Education, and Bond’s close friend and colleague for more than 40 years. “He was a true-blue dirt anthropologist who grew up in the discipline when it flourished. His work on the Yombe of Zambia, for example, steadily stands the test of time. His meticulous description of the history of the Yombe is now the official account of the tribe. Of that, George was really proud.”

In 1962 Bond began interviewing elderly Yombe men and women as a counterweight to his study of records kept by British colonial administrators. In 1975, he published a book, The Politics of Change in a Zambian Community, which traced the political and intellectual development of the Wowo, the ruling Yombe clan, from the late 1800s through the modern era, as they navigated conflicts within their own ranks, converted to Christianity, were educated in mission schools, forged a working relationship with British colonial rulers and, ultimately, secured their place in Zambia’s independence movement.

In his writings on HIV/AIDS, Bond argued that Uganda, considered one of the few African success stories in fighting the epidemic, was able to limit contagion only when it rejected standard Western public health approaches and focused instead on mobilizing women, children, orphans and the elderly. His coedited study, African Christianity (1980), explores the ways that African politicians like Alice Lenshine and Kenneth Kaunda used religion to create nationalist independence movements. And his most recent volume, Contested Terrains and Constructed Categories (2002), coedited with Nigel Gibson, brings together essays, most authored by Africans, that challenge Western techniques of “manufacturing Africa’s geography, African economic historiography, World Bank policies, measures of poverty, community and ethnicity, the nature of being and becoming, and conditions of violence and health.”

“George was a genuinely collaborative intellectual. He brought people in, and it didn’t matter whether or not you were an anthropologist,” says Gibson, who worked for Bond during the 1990s when Bond served as Director of African Studies for all of Columbia University. “Partly that was because he always wanted to build up others, particularly young scholars as they came up. Partly it was because of how he approached intellectual questions. He always talked about people in academia as lumpers and splitters. Either you would lump things together or you would split them apart. He was a splitter, in the sense that he was not one for blanket assertions. He preferred fine grained analyses based very much on asking what the relationships were between people in different domains.”

At TC, Bond revived the College’s Center for African Education, created a certificate for students with African expertise, and began editing a series of books, Teaching Africa, for use by New York City public school teachers. Emulating his own mentors, he shepherded his students’ lives and careers, finding jobs for them and connecting them with others in the field. “That,” he once said, “is how academe is supposed to run.”

“George truly set me up for a career of doing analysis of institutional minutia, which is something very difficult to teach,” says Joyce Moock (M.A. ’69, Ph.D. ’74), Bond’s first doctoral student and former Managing Director for the Rockefeller Foundation, who focused on helping African universities and other organizations build local capacity. “He was sort of a Sherlock Holmes of anthropology, going after the mystery and solving it with microscopic clues.

He conveyed the importance of being in the field, of listening, of case studies, of getting a contextual view. We were always looking to hire people with that big-picture view — scientific entrepreneurs, non-linear thinkers — but those skills weren’t on their resumes. You couldn’t know until you’d worked with them.”

In particular, Bond “overreached to make sure people of color were acculturated” says Portia Williams, his former doctoral student and currently Director of International Affairs at TC. “He understood that for black students, whether from Africa or the U.S., coming into this environment could sometimes be a unique experience. He lit a fire under black students. You couldn’t be behind. He always wanted to make sure you were at your best. It mattered to him. But he never treated white students with any less consideration or care.”

No one would ever confuse Bond politically with Henry Adams, but like Adams, Bond was the scion of a family that, within certain spheres, held the stature of royalty. Like Adams, he wrote about history and intellectual traditions from an acute sense of where he, personally, stood within them. His father, J. Max Bond, served in the U.S. State Department and was the founding President of the University of Liberia, conferring upon his children a peripatetic upbringing that included stays in Africa, Haiti, Afghanistan and university campuses throughout the American South. Bond’s mother, Ruth Clement Bond, sewed the first black power quilt in Tennessee during the 1940s, became President of the African American Women’s Association and led fact-finding missions in Africa for the National Council of Negro Women. His uncle, Horace Mann Bond, authored the landmark social science text Negro Education in Alabama: A Study in Cotton and Steel (1969), while another uncle, Rufus Early Clement, was President of Atlanta University and the first black since Reconstruction to hold public office in Atlanta. Bond’s late brother was the internationally known architect J. Max Bond Jr., and his cousin is the civil rights activist Julian Bond.

Bond’s efforts to represent Africa in global intellectual history built on the work of earlier black intellectuals and writers such as William E. B. DuBois, J. E. Casely Hayford, William Henry Ferris, J. E. K. Aggrey and Edward Wilmot Blyden, who, beginning in the late 19th century, consciously sought to craft a black African historical narrative. As Columbia’s Diouf has written, their efforts (which drew on the work of white anthropologists and ethnologists such as Franz Boas and Leo Frobenius, who debunked the idea that race determined culture) were part of a broader conversation among blacks in Europe, the United States and Africa that focused on Africa itself as both a physical and spiritual homeland.

White-haired and goateed in recent years, Bond himself favored tweeds, sported a cane and spoke with an English accent, something, he admitted, that even family members wondered about, since he was born in Tennessee. Yet even as he took pride in the remarkable accomplishments of his family and his race, he sought to remind people, including members of the American black elite themselves, of the institutions that helped to shape them. These included historically black colleges and universities, but also philanthropic institutions such as the Rosenwald Fund, a scholarship program created by the founder of Sears, Roebuck & Co. that supported an entire generation of black intellectuals, including Bond’s father and uncle, and also Ivy League schools and their ilk.

“Black elites send their kids to Harvard and Yale, and they don’t talk about it, but the fact that you go to Harvard or Yale puts you at an advantage,” Bond said. “I hate colonialism. I’m dead set against it; don’t get me wrong. But I also like a sound education. And that makes me a conservative -in the sense of conserving that which is worth conserving- and a radical in the eyes of others, in the sense of going to the root of things.

“I would argue that the field of anthropology is essential to understanding the whole process of education,” he added. “And I’m not talking about just schools, because education is part of the human process of evolution. So it is essential to look at the sociological environment in which people operate as well as the internal environment of the school itself. Because a great deal of time is not spent in learning, in acquiring of knowledge as we understand it, but in social relationships. And to what extent can you integrate learning into the social relationship itself? In other words, I am a follower of Cremin, who set out his notion of education, and that may be why he hired me.”

“HE LIT A FIRE UNDER black students. You couldn’t be behind. He always wanted to make sure you were at your best” Portia Williams

Condemned To Make A Meaning

A conversation about Maxine Greene with Janet Miller, Professor of English Education and Carole Saltz, Director of Teachers College Press

Professor Emerita Maxine Greene has been called one of the most important education philosophers of the past 50 years and an idol to thousands of educators. Born in 1917, Greene recalled being “brought up in Brooklyn, New York almost always with a desire to cross the bridge and live...beyond and free from what was thought of as the ordinary.” She attended Barnard College and New York University and joined TC’s faculty in 1965 as an English instructor and Editor of the Teachers College Record. Before interviewing, she waited in a restroom at the College’s Faculty Club because the club the admitted only men. In works such as The Dialectic of Freedom (1987), Landscapes of Learning (1978) and Teacher as Stranger: Educational Phil-osophy for the Modern Age (1973), Greene exhorted readers to “look at things as if they could be otherwise.” Deeply influenced by the philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, she wrote of “young persons lashed by ‘savage inequalities’...whose very schools are made sick.” Here, she said, were the real tests of “teaching as possibility.” ; TC Today asked Janet Miller, who wrote her dissertation on Greene, and Carole Saltz, who edited several of Greene’s books to recall a thinker, teacher mentor and friend.

On Choosing How To Be

TC TODAY: The idea of a philosopher in this day and age whose thoughts have so much power for so many people seems amazing.

SALTZ: Well, some might say that Maxine was not even a great example of a philosopher. Because she was so active. She thought her thoughts, and they were big thoughts, but the life of the mind was met by this tremendous drive to be someone who made a difference.

MILLER: She would say, “I do philosophy.” Her philosophy was about being in the world and asking, “How am I seeing?” “What’s framing how I’m seeing?” And that all came out of her philosophical orientation, which was existential phenomenology [which, Miller says “studies structures of conscious experience from the first-person point of view and especially focuses on complex issues of choice and action in concrete situations”]. She would quote Sartre — that as humans, we’re condemned to make meaning, to choose how we want to be in the world, so as to make it better. She took the questions that novels like Camus’s The Plague can represent — What is the meaning of life, especially when plagues of all sorts challenge us, and what can I do?- as the challenge of being alive.

TC TODAY: “Existential” sounds bleak. Yet her thinking seems joyous, or at least very much about the here and now.

SALTZ: It was more like, “Hope for the best but plan for the worst.” She understood - she lived, really, with her father’s suicide and her daughter’s death- that life is filled with tragedy and pain, but also with beauty. Art was her means of understanding and of trying to help the rest of us- especially young people, who are hungry for beauty -transform ourselves and our worlds. When art got left out of the conversation, it made her crazy.

TC TODAY: She writes that reality is what’s interpreted. She says, “I’m interested in the interaction between myself and the Monet painting on the wall.”

SALTZ: It’s always transactional. It’s never simply looking. You’re never passive with art.

MILLER: Your seeing is value-laden, a process of constant interpretation, depending on your particular situatedness in the world. For each of us that’s different, because the world is a conflicted place. So Maxine paid attention to “How is it that I’m seeing things this way? What has become so habitual that I take it for granted when, in fact, I should be questioning it?” She said practically every day of her life that the thing she feared most was numbness. Indifference. Passivity.

SALTZ: She talked about the aesthetic being the counter to anesthetic. Art as a way to find intersections with other human beings.

On Freedom and Morality

TC TODAY: Was there a tension for her between freedom and morality? She talks about obligations to others and what ought to be. Yet she laments how the two men in Brokeback Mountain have to give each other up and return to their families.

MILLER: I think she was speaking very deeply about ethics and how people should be treated. I would not interpret anything that she wrote or spoke about or lived as “anything goes.”

SALTZ: She wasn’t somebody who thought, “If that’s what they believed, then that’s what they believed.” She had a very strong sense of justice and of what’s moral. At times that was in tension with the idea that we need to be open. But it never prevented her from understanding that sometimes you have to draw a line and fight for what you believe.

MILLER: She expressed outrage on a daily basis. She read The New York Times every day, and boy, she had strong opinions.

SALTZ: She was very focused on high-stakes testing, on what it was doing to children and teachers. My son, who’s a teacher, knew Maxine really well and said her views on that subject reminded him of Gide — “Tyranny is the absence of nuance.” And she put her money where her mouth was. People asked her to talk at little gatherings, at large gatherings, and she would do that.

On Feeling Faux

TC TODAY: In the film about her life [Exclusions and Awakenings: The Life of Maxine Greene], you see people’s faces when she’s speaking. And she was obviously mesmerizing.

SALTZ: She mostly read her papers, but it was fantastic.

MILLER: She had this habitual stance of gazing up at the ceiling, in between looking down and reading her paper.

SALTZ: She’d lose her place.

MILLER: A little bit of swaying. But the minute she started — I mean, we’ve both been in crowds of 400, 500, 600 people, all just enraptured. And these were very academic papers. Not fluff.

SALTZ: The last time I saw her speak, she was 94. She was in her wheelchair. And she was brilliant. She was talking to a group of early childhood educators. At the end, they were coming up to her and saying, “That changed my life.”

TC TODAY: At TC, I’ve met a music professor, a movement scientist, a fiction writer who all say: “Nobody shaped my life more than Maxine Greene.” Was part of that her invitation to interpret through personal experience? She writes in The Dialectic of Freedom, “I insist that people tell their stories.”

MILLER: But she’d want you to question your stories.

SALTZ: It was making meaning out of the story.

MILLER: What interpretations are you habitually bringing to these stories? How might you see them differently?

SALTZ: And how is that story a problem for someone else?

MILLER: When we would visit, it was, “What are you doing now?” And she’d say, “Really? Is that what you really think?” It was constant interrogation, but not for the sake of arguing or lecturing. It was her mode of being.

SALTZ: And she would do the same thing to herself.

MILLER: Oh, God, yes. She was quite aware of her own conflictedness. She would talk about the social mores of the time in which she grew up. “Why did I think I had to be married? Why, when the marriage ended, did I have to go right into the next marriage?” And yet never denying, “Yeah, I thought that. I did that.”

SALTZ: She suffered endless guilt about her own privilege. She felt guilty that she wasn’t out there on the lines with the Occupy Wall Streeters. And we would look at her and go, “You’re 92; you’re in a wheelchair. You’re giving what you can give.”

MILLER: She loved Moby Dick. She would say, “Oh, dear, I realized how much I love the white, male European authors.” She’d feel very guilty about that.

SALTZ: But she also believed that individual works of art transcended their time. And she wouldn’t feel she had to have a reason. She was comfortable that art gave her something transformative, and that whatever she could give back created opportunity for other things to happen.

MILLER: We talked about feeling faux. As women in our roles in the world. She was a renowned professor who had been President of AERA [the American Educational Research Association], and yet she still felt this aspect of fooling everyone.

SALTZ: She said, “That’s why I never had a business card made up. I thought somebody would figure it out and take my card away from me.”

MILLER: In Landscapes of Learning, she has a section called “Predicaments of Women.” And we would talk about labels that a lot of us have trouble with. Second-wave feminisms, you know, with a fairly fixed notion of the category of women. We would talk for hours and hours — even in the last few weeks. One afternoon in the hospital, she said, “What’s it mean, Janet, to be a woman academic? What are you thinking now?”

On Legacy and Revolutions

TC TODAY: What do you think Maxine’s legacy will be?

SALTZ: I would start with her writings. They’ve had great impact on teachers in the classroom. The teachers of teachers. Superintendents, principals.

MILLER: She’s read around the world. More and more there are requests for her books to be translated.

SALTZ: We’ve still got all of these books of hers in print, and they sell. And because of her foundation, the Greene Grants, there are people dancing, making music, making art today. Schools, too. They weren’t big grants, but they were important.

MILLER: She influenced so many different fields of study. I’ve met nursing students who built their inquiries around Maxine’s writings. They do a lot of qualitative research and case studies.

SALTZ: Medicine, too. The idea of narrative, of understanding what your patients are saying. And her teaching as Philosopher in Residence at Lincoln Center. Droves of teachers would work with her. She gave the big keynotes, but she’d be in the small workshops, too, taking her shoes off and running across a mat or dancing. She acted, too. Not long ago, she was in an off-Broadway piece.

TC TODAY: Did she inspire political revolution with her thinking? Or more of an approach to life?

SALTZ: I think both. There are groups out there right now that were formed in Maxine’s dining room. And if you were up on Facebook or somewhere, there are groups trying to transform public education as a direct result of Maxine’s influence and support.

MILLER: And we can’t forget, she went off to fight the Spanish Civil War. She stood on street corners, giving speeches. And she was on the boat headed over there.

SALTZ: A boat that almost sank, on its way to the Lincoln Brigade. She stayed in touch with the Lincoln Brigade forever. The sense of agency that resulted from that was an influence her whole life.

TC TODAY: She cut across so many fields. Did she feel that formal disciplines matter?

SALTZ: Well, the first thing she’d say would be to watch the labels. She did feel the academy makes it difficult to bring in a multiplicity of disciplines. But she would warn us not to get bogged down in something less important than the big idea. Whatever “the big idea” is.

MILLER: Don’t let disciplinary or departmental boundaries stand in the way of how I might imagine, envision and take action.

SALTZ: For her, questions were the answers. But also, if there is a reason for certain formalities, then maintain them.

MILLER: Students would say to her, “Why is what you write so difficult?” And she would say, “Do the work.” Meaning, disciplines have histories, so if you want to understand my work more clearly, read Sartre. Read Merleau-Ponty.

SALTZ: But behind “Do the work” was, “I know you can.”

TC TODAY: Are we in danger of romanticizing her?

SALTZ: It’s very important that we guard against that.

MILLER: She would always say, “I am not an icon.”

SALTZ: She was uncomfortable with anything that set something in stone —

MILLER: She couldn’t keep becoming, then.

SALTZ: “I am what I am…not yet”

Published Friday, Jan. 23, 2015