Heeding Her Call: Urban Education responds to Mariana Souto-Manning’s framework for re-centering minoritized communities in social justice research

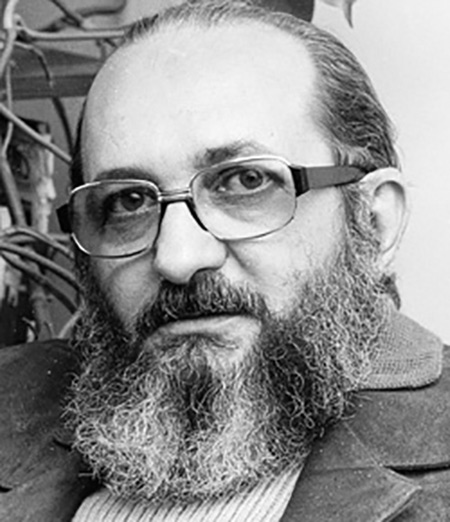

Mariana Souto-Manning may have raised the bar: An entire special issue of the journal Urban Education, published in June, responds to her theory and method, critical narrative analysis (CNA). Souto-Manning, Associate Professor of Early Childhood Education, proposed CNA as a means of bridging analyses by researchers of how language helps establish and reinforce power relations in society and the everyday narratives through which minoritized individuals and communities make sense of their own experiences.

“Mariana has repeatedly called on the research community to think carefully about what we’re asking in our studies, because whoever is doing the asking sets the lens,” says Limarys Caraballo (Ed.D. ’12), Assistant Professor of English Education at Queens College, City University of New York, and guest editor of the Urban Education special issue. “Her ultimate message is that we need to incorporate what the participants themselves recognize as problems so that we don’t perpetuate their marginalization, but instead honor, support and sustain their cultures, knowledge and emerging identities.”

Titled “Co-Constructing Identities, Literacies and Contexts: Sustaining Critical Meta-Awareness with/in Urban Communities”, the Urban Education special issue consists entirely of papers authored by younger scholars of color who have been directly influenced by Souto-Manning’s work, including Caraballo.

“[Mariana's] ultimate message is that we need to incorporate what the participants themselves recognize as problems so that we don’t perpetuate their marginalization, but instead honor, support and sustain their cultures, knowledge and emerging identities.”

— Limarys Caraballo

In formulating CNA, Souto-Manning drew on the work of Paulo Freire, the Brazilian educator and philosopher, who, as Souto-Manning puts it, identified the need for oppressed populations to develop a “critical meta-awareness” that would enable them to “problematize current realities as unchangeable givens” and instead insist on “probing the historical and cultural underpinnings that shaped any oppressive situation and system.” In her 2014 paper, she writes that through CNA “individuals engage simultaneously with the word and the world – not only making sense of their lives through co-constructing narratives, but questioning and refuting institutional discourses which may be found in these very narratives…oppressing their very lives (or at least being used to justify such oppression).”

The articles in the Urban Education special issue examine different communities in different ways, but share a common focus on demonstrating the participants’ meta-awareness of their own marginalization. In one paper, Latrise P. Johnson, an Assistant Professor at the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa, uses critical narrative analysis to analyze her conversations with Teamer, one of her former black, male high school students as they co-construct a narrative of his experiences in and out-of-school spaces.

“Black males are often viewed from a deficit perspective even though they have rich cultural and community resources outside of school,” says Caraballo. “Johnson shows how Teamer was engaged in literacies through his use of language, music and poetry with caring teachers like herself. He was a producer and consumer of literacies that are not typically honored or validated in academic spaces, yet was aware of society’s expectations for black males. When he got in trouble outside of school, he was framed by all of these stereotypes of black males, despite his desire to succeed.”

“Addressing the question ‘critical for whom?’ theoretically and methodologically helps us avoid colonizing participants with our own views and instead leads us to identify what is critical for them, according to them.”

— Mariana Souto-Manning

Ultimately, Johnson explains how Teamer developed critical meta-awareness and (re)authored his history in ways that refute colonialist perspectives and humanize his experience.

In another paper, Danny Martinez, an Assistant Professor at the University of California, Davis School of Education, explores how teachers’ correction of bilingual students’ language demonstrates their own ethnocentric perspectives on how students should speak. The teachers’ corrections frame the students as lacking, but the author focuses on how students leverage their own knowledge of language practices to convey knowledge. He looks at how they code switch in ways that demonstrate sophisticated mastery of language, and he contrasts that with teachers’ deficit perspectives.

And in a paper of her own, Caraballo describes how middle school students felt compelled to take up the language and literacy expectations of teachers and administrators, often obscuring their own cultural identities and literacies or keeping them outside of school. She examines how students’ critical meta-awareness serves to challenge educators and researchers to (re)imagine curriculum and pedagogy in ways that trouble discourses that regulate and constrain students’ academic lives and futures.

Yet students who did conform to traditional expectations were aware that their own literacies and identities were being marginalized, Caraballo found. “They felt that they were often simply writing to the rubric rather than expressing themselves in any meaningful way.”

In addition to articles authored by Johnson, Martinez, and Caraballo, the issue also includes articles authored by Tim San Pedro (Assistant Professor, The Ohio State University) and Melody Zoch (Assistant Professor, University of North Carolina at Greensboro).

Collectively, the articles in this special issue offer powerful representations of how critical meta-awareness engenders pedagogies and methods through which researchers, educators, and youth may co-create positive social change, challenging inequities and interrupting education injustice.

Souto-Manning has been recognized before for the impact of her work. During 2014-15, the Early Childhood Education Assembly of the National Council of Teachers of English established the Mariana Souto-Manning Teacher Scholarship for early childhood teachers who honor diversities and engage in equitable practices. Souto-Manning has also received the 2009 Early Career Researcher Achievement Award from the National Conference on Research in Language and Literacy; the 2016 American Educational Studies Association Critics Choice Book Award for Reading, Writing and Talk: Inclusive teaching strategies for diverse learners, K-2 (Teachers College Press, 2016, co-authored with Jessica Martell); and the American Educational Research Association’s Division K Mid-Career Award.

Still, she seems particularly gratified by the Urban Education special issue.

“I was overwhelmed when I learned of this special issue,” Souto-Manning says. “Honored, humbled, and truly touched. The scholars in this special issue of Urban Education are a new generation of researchers of color. They are the future of critical research with communities of color. They are pushing the field in critical and significant ways. I was so honored to learn that my questions inspired them and that my work pushed their thinking. I think this is what every researcher wishes for. That in some way their research inspires and charges a new generation. That it can serve as a foundation from which a new generation builds.” – Joe Levine

Published Friday, Aug 18, 2017