On a weekend – a holiday weekend, mind you – fifth-grader Steven Decker hauled himself out of bed early – not once, but twice – to journey from his home in Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood to Teachers College on Morningside Heights.

Steven, a self-proclaimed “big sleeper,” was not serving punishment for some misdeed. He came of his own free will to attend “Raise Your Voice,” a workshop offered over the long Columbus Day weekend by the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project (TCRWP) for 94 young social justice activists from schools in New York and neighboring communities seeking to burnish their prowess in writing poetry, narrative writing and the spoken word. “Raise Your Voice” was conducted with the support of the Rowland and Sylvia Schaefer Family Foundation, co-directed by Teachers College Trustee Marla Schaefer.

“This is an amazing program,” Schaefer said. “Kids are watching us, especially in the current political climate, to see what we do and if we do anything. When you give them a platform to raise their own voices, the passion that comes out will knock you over. For anyone who feels that the world is going to hell in a hand-basket, listen to these kids, and you know we'll be OK.”

For decades, the Reading and Writing Project, founded and led by Lucy Calkins, Robinson Professor of Children's Literature has worked with teachers, administrators and support staff to transform young people in classrooms across New York City, the nation and the world into confident, passionate readers, writers and thinkers.

PEER DIALOGUE The day’s real work took place in smaller cohort groups where kids learned about, among other things, the power of collaboration.

But “Raise Your Voice” marked the Project’s first large-scale institute-style event with kids, so organizers didn’t know what to expect.

Judging by the reaction of Ameres Houston, a fifth-grader in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn, they need not have worried.

“I always hear that kids have a voice,” she confided to a “Raise Your Voice” instructor. “But I never, ever really felt it – until now.”

“Raise Your Voice” featured keynote addresses by Erika Andiola, an immigration activist and former Bernie Sanders campaign aide, and Olivia Van Ledtje (a.k.a. LivBit), an 11-year-old advocate for literacy and social media.

But the real work took place in intense, boisterous workshops within smaller cohort groups led by instructors who relied on narrative techniques in short-feature filmmaking, interactive exercises and, above all, the power of peer dialogue to hone the writing skills of workshop participants.

“It opened up new ways to learn,” said Sophia Rodriguez, a fifth-grader in midtown Manhattan.

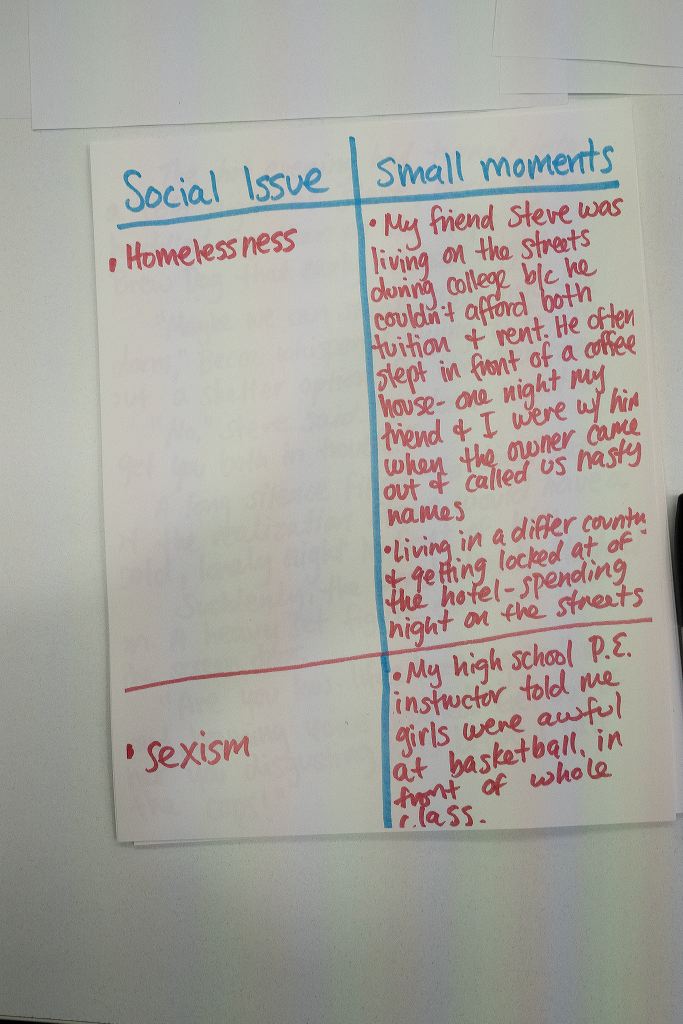

Rodriguez, Decker, Houston and their fellow attendees – all from TCRWP partner schools – submitted admissions essays on issues such as the environment, race and ethnicity, immigration, gender and sexual identify, social media use and misuse and gun violence. Many drew on their own experiences: for example, Houston wrote about her experiences with the New York State Family Court and foster care system, and one young man of Middle Eastern descent described his encounter with a stranger who accused him of terrorism.

I always hear that kids have a voice. But I never, ever really felt it – until now.”

—Ameres Houston

“The students felt empowered,” said workshop co-instructor Jermecia Trenell, a first-year student in TC’s Literacy Specialist program and a former fifth-grade teacher in the Atlanta Public Schools. “They were conscious of global issues and completely locked in to what they can do to make this world a better place, now and as adults. I’ve never experienced anything like it. And you could see the growth from day one to day two.”

The participants were chosen by workshop co-organizers Mary Ehrenworth, Deputy TCRWP Director, and Associate Director for Middle Schools Audra Robb, who gave equal weight to writing ability and student passion for a cause. Robb and Ehrenworth also sought a balance of students from different backgrounds.

Discover TC’s Literacy Specialist program

A common feature across each of the smaller student groups was that the writing, quite intentionally, was “all in their hands,” noted TC student Elana Fruchtman, a master’s degree candidate in the Literacy Specialist program, former Seattle elementary school teacher and the co-instructor – along with Ehrenworth – of a fifth-grade workshop.

The students felt empowered. They were conscious of global issues and completely locked in to what they can do to make this world a better place, now and as adults. I’ve never experienced anything like it.”

—Jermecia Trenell

The average age of the students in the Ehrenworth-Fruchtman workshop hovered around 10, but the awareness of societal issues seemed characteristic of a more sophisticated age-group.

Ten-year-old Sydney Obstler, for example, pulled out her digital notebook at mid-afternoon on Sunday to compose an extemporaneous poem that she then appended to her admissions essay on immigration:

We are the light we stand tall

We are light we stand tall when the darkness comes

We are the light we stand tall and we beat the darkness.

We are the light of the future.

The granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, Obstler was drawn to her topic by news accounts of immigrant children separated from their parents at the Mexican border.

Their stories, she wrote, evoked the loneliness of the first time she was apart from her family at a sleep-away camp. The reality of that loneliness, Obstler said, compounded by the terror of forced separation and the fear that they might never be reunited with their parents, was something experienced by “these children, every day.”

Rodriguez, a daily reader of the print edition of The New York Times (“I want to know what is happening”) took an opportunity during the workshop times set aside for writing to expand on an essay decrying social media.

“Every day, I watch my friends, family, strangers all lose themselves on social media,” she wrote. “They rely on it for all their information.” As a result, she added, they have lost the ability to learn and communicate by “actually talking to people, watching the news, reading an actual newspaper.”

NOT MINCING WORDS Kids took on topics that included the environment, race and ethnicity, immigration, gender and sexual identify, social media use and misuse, foster care and gun violence.

Steven Decker was likewise motivated by a sight familiar to all New Yorkers: “I walk the streets of Brooklyn and see trash left and right with no person picking it up. The citizens of New York may not care. But I do. We need to organize … and put trash where it belongs.”

Ameres Houston in workshop conversations and through the written word traced what she characterized as “my situation” – a 10-year odyssey of family court appearances and placements in foster care homes.

“I feel very strongly,” she wrote, “that the court system should be MUCH more concerned about children’s feelings because then children won’t feel so alone and dead inside.”

Houston was among the many other students vowing to leverage the power of their writing to propel friends and classmates toward social change.

“It is my passion to get my point across so foster children know that they aren’t alone,” said Houston.

Decker, whose father earned a Ph.D. at Columbia in his late 20s, departed Teachers College no worse forgoing two opportunities to sleep. Beyond being affirmed in his desire to clean up Brooklyn’s streets, he said, “I get to brag that I got here when I was 17 years younger than my dad was.”