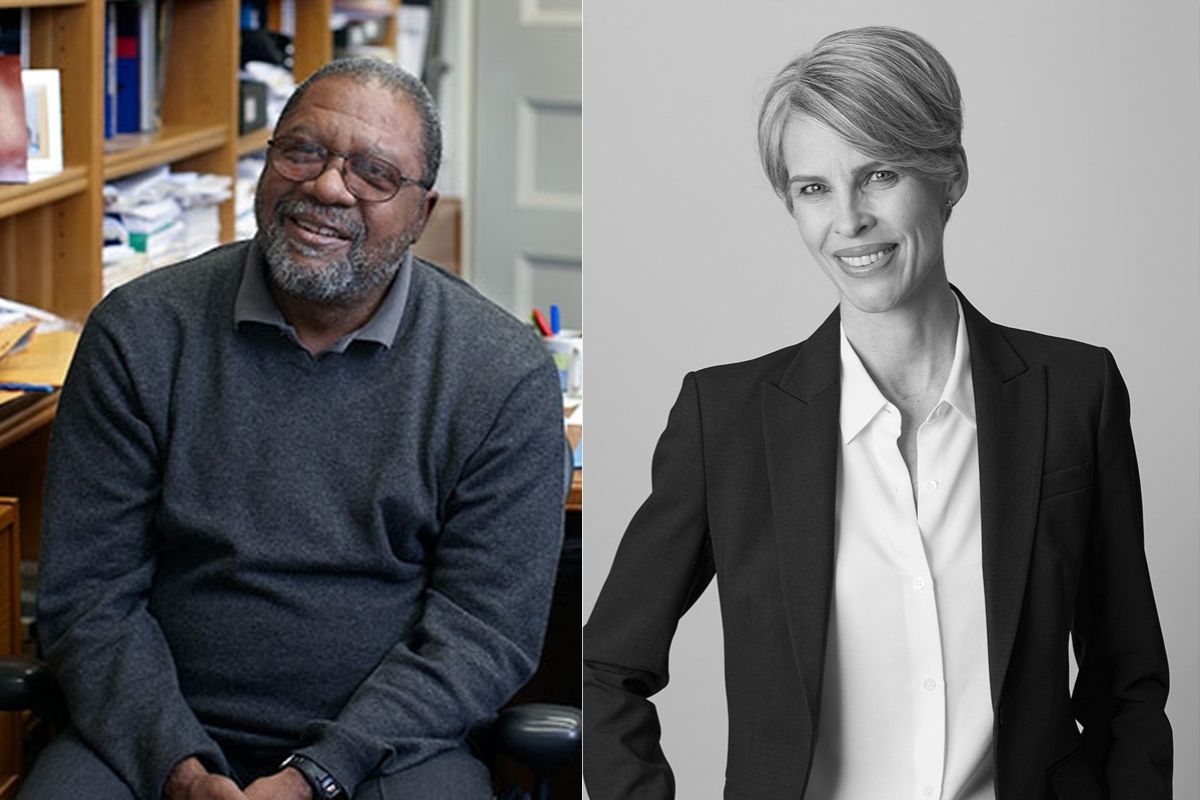

Michele Barakett took just one course with Robert T. Carter while she was a student at Teachers College. She didn’t know him well and didn’t stay in touch after earning her master’s degree in counseling psychology.

But that course, the Racial Cultural Counseling Laboratory, was “transformational, life-altering” – so much so that Barakett (M.Ed., M.A. ’01), together with her husband, Tim, has created the Robert T. Carter Fellowship, a $250,000 endowed fund that will support a TC student who has completed his or her first year of doctoral studies and is from an historically disenfranchised or oppressed group in terms of educational opportunity or economic viability.

“I don’t think it ought to be the job of black people to teach white people about racism, but Dr. Carter took on that task,” says Barakett, who is white, and now a practicing psychologist who has served as a diversity coordinator in a New York City independent school. “His class was experiential – you were asked to examine your racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, gender and religious identification. He put himself out there, and sometimes students shut down and became defensive – but for me, the opportunity to examine my white racial socialization was a gift. That class demanded it of me, and it was a real awakening.”

Give the Gift of a TC Education

- Pledge $50,000 to create a new endowed scholarship in your name or someone else's

- Contribute to an existing tribute or program fund scholarship

- Support a TC Fund Scholar or designate your TC gift to financial aid

Contact Susan Scherman at 212 678-8176 or scherman@tc.columbia.edu

Carter, Professor Emeritus of Psychology & Education and the recent recipient of a lifetime achievement award from the American Psychological Association’s Council of Counseling Psychology Training Programs (CCPTP), has devoted his recent research and scholarship to creating legal redress for race-based harm and stress by documenting the damage it causes to individuals. While women, same-sex couples and other marginalized groups have slowly attained a measure of legal parity, he has argued, “rights, services and outcomes remain markedly inferior for those oppressed because of their skin color.” To that end, Carter has created the nation’s the first and only instruments for measuring race-based traumatic stress and the different kinds of racism people are exposed to. The categories range from “avoidant racism” (refusal to offer people of color a job or a loan) to “hostile racism practices” (police profiling, stop-and-frisk). Carter published his instruments in 2013, 2015 and 2016 in the journals Psychological Trauma and Traumatology – “a big step,” he said in an interview two years ago, “because the people and the courts require expert testimony to be based on accepted scientific evidence in your field.” He is currently working on two books that address these issues.

For Michele Barakett, Robert T. Carter’s experiential-skill-didactic course, “Racial-Cultural Counseling Lab,” that taught students about race and cultural counseling through self-exploration and skill-based practice was “life-altering.”

In his teaching and writing, Carter has similarly contended that “race is the core difference” and that continued violence against people of color “is not a matter of individual prejudice but rather one of systemic racism” reflecting “centuries of negative outcomes for people on the wrong side of the color line.”

Barakett says Carter’s lab course made her reflect back on her own upbringing.

“I’m a white Canadian, and I had always thought about race in terms of black and white,” she says. “But I hadn’t reflected on the racial segregation in my own area, where the majority of people in town were white, but around it were several First Nations reservations – the indigenous Canadian people. Nor had I considered the impact of that segregation on my own sense of self.”

To have a non-racist identity requires that I examine, every day, the environments I live and work in; that I notice race and do something about the injustice I see.”

— Michele Barakett

During one class session, when these and other aspects of her thinking were the focus, Barakett says, “I became very emotional and overwhelmed, and then I just shut down. And Dr. Carter suggested that I might not have a high level of comfort with strong emotions, and that there might be a racial aspect to that – that in my socialization as a white person I’d been deprived of something. He was really skilled, and even though it was hard, I felt he wanted the best for me and was there to help. I experienced him as a skilled clinician. At the end of the day, I felt I was in very competent hands.”

Barakett says she draws on those insights in her day-to-day life – “To have a non-racist identity requires that I examine, every day, the environments I live and work in; that I notice race and do something about the injustice I see” – and that she still consults Carter’s books such as The Influence of Race and Racial Identity in Psychotherapy: Toward a Racially Inclusive Model (Wiley 1995) when she’s working on new projects. The latter include a racial literacy curriculum for K-8 students that she’s funded, which is currently piloting in independent schools and will be offered free on the Pollyanna, Inc. platform.

Barakett’s gift is “a very powerful way to say that learning about race and culture is valuable, to the point where it should be made part of the institution,” Carter says. “And that is very important to me.”

Even though Barakett feels that Carter has much to teach white students, her gift is designated for a student from a disenfranchised or oppressed group. “That reflects both Dr. Carter’s wishes and my own,” she says. “There was a racially diverse group of students in my program, and that added a great richness to my experience. So I hope that the program will continue to be able to attract talented students from under-represented groups. We also need to ensure that a diversity of great scholars continue contributing to the research literature.”

For his part, Carter calls Barakett’s gift “a very powerful way to say that learning about race and culture is valuable, to the point where it should be made part of the institution. And that is very important to me.” On a personal level, he added, “I was left speechless. Really? I had that impact?”