Susan Fuhrman’s 2007 Inauguration Speech: Living Up to the Legacy of Teachers College

Inauguration Remarks by Susan H. Fuhrman, Tenth President of Teachers College, Columbia University

First, my thanks to each of the many speakers who welcomed me here today. I am truly honored and humbled by your presence and your words. Second, I am overjoyed beyond words to return to Teachers College, my alma mater, as its 10th President. I defended my dissertation exactly 30 years ago this month at a lunch meeting, I think, at Butler Terrace-'"where we had lunch today. I still have to pinch myself to believe that I've made that journey.

Fortunately, I have never walked alone. I have always had loving family members, superb colleagues, and the most devoted of friends right by my side. Many of them are here to share this incredibly special moment in my life-'"one I will treasure always. It is wonderful to see all of you here.

And it's good to be home.

It is also good that we gather in this magnificent house of worship, where the sermons of Reverend. James Forbes Sr. have raised spirits higher than the soaring belfry.

There is a huge difference, Dr. Forbes reminds us, between "doing something" and "getting something done."

Teachers College earned its pre-eminent reputation by getting a lot done. Near the end of his life, Dr. Harry Passow, an eminent TC professor who virtually founded the field of urban education, delivered an address that powerfully resonates in 2007.

Ours, he said, "is a tradition of helping policymakers and practitioners of all kinds acquire the knowledge, insights, skills, understandings and commitment to ask the right questions, to get beyond the rhetoric of the moment, and to make a difference in whatever kind of educative setting they function."

Making a difference. So with a nod to Professor Passow and Dr. Forbes, I will reflect on Teachers College's historical legacy of making a difference. And I will describe how we can-'"and must-'"draw on our legacy to leave an even more consequential legacy for those who follow.

Throughout our history, great thinkers have asked fundamental questions that indeed have taken us beyond the rhetoric of the moment-'"and their answers profoundly altered or even launched whole fields of inquiry.

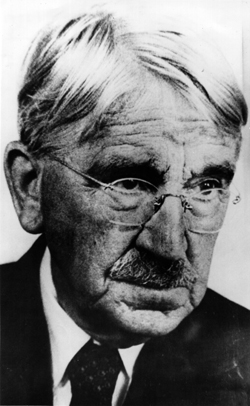

Any discussion of our legacy rightly begins with John Dewey, even though initially, he only lectured here as a member of the Columbia faculty.

American schools of the late 19th century were rigid and cold places where teachers held themselves at a formal and often forbidding remove from young children.

Dewey's ideas quite simply breathed life into American education by creating the modern American classroom. He asked fundamental questions about human perception and how children really learn. Dewey believed that education should build on the learning in every day life and foster creative problem solving.

As Lawrence Cremin, our seventh President, wrote in his history of TC's first half-century, "We are all heirs to the formulations of Dewey and his colleagues."

As we heard earlier, Teachers College created its own Lincoln Experimental School, modeled on Deweyan ideas. First graders at Lincoln studied community life by building a play city, complete with buildings, trains, electric lights, furniture and doll residents. The sixth grade learned how to make paper and books, and how to print and publish a magazine. Eighth graders explored the workings of a heating apparatus, and children staged their own musical productions-'"including, in one program, an excerpt from Beethoven's Ninth Symphony played on pan-pipes of their own making.

The Lincoln School's impact on the nation was monumental. The faculty published volumes; they developed curricula and field-tested them in cooperating public schools. They helped to overhaul school systems in Pittsburgh, Denver, Cleveland, Baltimore, Rochester, Chicago and St. Louis.

The impact of Dewey and the Lincoln School serves as a metaphor for TC's history. The ideas developed here and the research that tested them changed the world; not just because of their intellectual power-'"but also because they were tested in the cauldron of practice and implemented in classrooms. These ideas fostered actual improvements that made a real educational difference.

Another path-breaking TC scholar whose work made a difference was E.L Thorndike. Thorndike pioneered in bringing empirical experimentation to education-'"and his findings in many ways provided a scientific basis for Dewey's intuitive understanding that learning occurs when the senses are engaged. Thorndike introduced the statistical method in education and psychology, invented a scale to measure quality of academic performance, and ultimately launched the achievement test movement. Like Dewey, Thorndike put his pedagogical ideas to work to assist teachers. For example, he wrote a book of vocabulary words, A Teachers Word Book, and a book about how to teach algebra.

TC's first enduring leader, James Earl Russell, who became Dean of Teachers College in 1898, also took up the charge of professionalizing educational studies through the integration of research and practice. Russell argued that teachers should be prepared as professional experts on a par with doctors, lawyers and engineers, with a curriculum anchored by the four pillars of general culture, special scholarship, professional knowledge and technical skill. He shaped and effectively institutionalized the field of modern pedagogical instruction and, by linking research with practitioner preparation, set a course that, in one form or another, Teachers College has followed ever since.

James Russell also set the cornerstone for another aspect of TC's legacy. Because he had found his own American education so wanting, he toured Europe to, in his own words, "see if there was not some better way." What he saw convinced him that there was-'"and in the spring of 1898 he introduced at TC America's first course in comparative education. From that time since, we have been the nation's leading exporter of educational theory and method, as well as a primary center for the study of other nations' educational systems, and a top destination for scholars from across the globe.

Russell's leadership also expanded the work of TC into fields closely allied with education: health and nutrition. In the early days of the 20th century, TC embarked on the broad vision it has sustained to this day, by recruiting pioneers such as Adelaide Nutting, developer of the first university-level nursing education course, her disciple Isabel Maitland Stewart, who founded the first scholarly journal in nursing education, and Mary Swartz Rose, who helped establish nutrition education as an academic discipline.

With us today are standout later 20th century scholars who expanded TC's early legacy through their groundbreaking research, influential applications, leadership in the world and broad vision.

Professor Emeritus Morton Deutsch has sought to define the conditions that lead to constructive ways of resolving conflict between couples, in schools or cities, or among nations.

In 1986, Mort founded the International Center for Cooperation and Conflict Resolution. The Center has trained New York City students, parents and teachers in constructive conflict resolution. And Mort's work also has influenced deliberations at the United Nations and American arms negotiations. Please join me in saluting Morton Deutsch.

You heard just a moment ago from another of our great emeriti faculty, Professor Edmund Gordon. One of the architects of the federal Head Start program in the 1960s, Ed founded TC's Institute for Urban and Minority Education, which became the nucleus of the College's engagement with schools and community organizations in Harlem.

For many years, Ed has advanced the concept of supplementary education-'"the idea that children from challenging backgrounds must be supported by an extensive scaffolding of caring community that includes after-school programs, counseling services, education for parents, and much more.

Ed brought that idea to fruition through his own efforts in Harlem and his partnership with others pursuing the same dream. Ed Gordon, Well done.

And then there is Professor Maxine Greene, our brilliant philosopher queen. Maxine is among the world's most widely read educational thinkers, a philosopher in residence at Lincoln Center, not to mention an inspiration to artists of every sort. Yet in the 1960s, interviewing for her position at Teachers College, she had to wait in the restroom because the Faculty Club admitted only men.

Maxine's great quest, as she has so often said, is to make young people "wide awake" to art. Yet her goal is also to stimulate "wide awakeness" of a much broader kind. "There are, of course," she wrote, "young persons in the inner cities, the ones lashed by -'savage inequalities,' the ones whose very schools are made sick by the social problems the young bring in from without," she writes. "Here, more frequently than not, are the real tests of -'teaching as possibility' in the face of what looks like an impossible social reality at a time when few adults seem to care."

Brava...Maxine-'Brava!

Maxine's work has asked us to imagine the possible; I now want to ask us to imagine greater possibilities for the future.

What must we do to build on the legacies of ground-breaking scholarship that informs professional preparation, makes a real world difference, a breadth of approach and leadership in the world?

What would it mean if we were to truly live up to our legacy at Teachers College? What is the something that we would get done? What legacy would we, in turn, leave to those who follow us?

First, our legacy demands that, like our predecessors, we will assure that our work always addresses the most important questions and seeks to produce definitive answers about the most pressing problems of education and social policy. By emphasizing health and psychology along with education, we must represent the interdisciplinary approaches that educational problems inherently demand.

Our scholarship agenda must remain far-reaching, addressing the questions that link education to the larger context in ways made possible by our broad vision.

We must, for example, produce scholarship that links human psychological development to learning in specific subjects.

We must produce scholarship that applies that knowledge to the development of curricula and the preparation of practitioners.

And we must produce scholarship that determines the best ways to join efforts to support communities and develop healthy social contexts to improve classroom learning.

Further, our legacy compels us to lead the way in preparing the next generation of top-flight practitioners. We must provide them with nurturing, research-rich environments. By strengthening the links between research and practitioner education, we can ensure that educators will benefit from the latest discoveries about human learning-'"and that they will become sophisticated consumers of research with life-long commitments to using evidence to improve practice; and become pioneers in creating new learning environments with emerging technologies.

At a time when education schools are ridiculed for failing to prepare qualified teachers, we must make the case for excellent, research-rich professional preparation.

Building on our legacy also means that we would leave a legacy to our neighbors and our city. Just as our predecessors taught us, it's imperative that we apply new insights and approaches to educational improvement especially close to home where there are great needs.

We must take on more responsibility for improving local schools and other educational settings by working closely with community and school partners. We have an historic commitment to equity and excellence in education. There's no better place to demonstrate that commitment than here at home in our Harlem community.

On a larger national scale, we must assure that our research reaches relevant policy and practitioner audiences. We must dedicate ourselves to applying our work in the most constructive ways toward making a real difference and delivering measurable improvement in outcomes for children.

Our legacy will also be to those who see the future in global terms. Increasing education and skill levels make the world more interdependent and competitive. As a result, education has become the most critical economic policy focus for both developed and developing nations. TC's international work will become more significant through many enterprises: through our research on comparative education approaches; through our many exchanges that enable educators to study with the most groundbreaking scholars even if they reside across the globe; and through enhanced efforts on the ground to help other nations who request it to improve their educational systems and professional preparation programs.

Strengthening these efforts will make the world even smaller and revitalize TC's reputation for world leadership that Russell envisioned.

The hallmark of our TC legacy is partnership. We will actively cultivate partners for our work foremost among them our neighbor just to the south, Columbia University. So much of what we hope to do and can do can be achieved or improved upon through work with Columbia, whether in public schools here in New York or in countries throughout the world.

Finally, if we live up to our legacy, we can fulfill a challenge that John Dewey posed nearly 80 years ago in his book Experience and Education.

Dewey exhorted educators to "think in terms of Education itself rather than in terms of some -'ism' about education." For, he wrote, "in spite of itself, any movement that thinks and acts in terms of an -'ism' becomes so involved in reactions against other -'isms' that it is unwittingly controlled by them. For it then forms its principles by reaction against them instead of by comprehensive constructive survey of actual needs, problems and possibilities."

Perfect advice for these ideologically fraught times. Only if we move beyond the isms to think about what truly works will we-'"as Harry Passow put it-'""prepare Americans for the 21st century and achieve the twin goals of equity and excellence beyond the current rhetoric level."

Above all others, equity and excellence are the goals that I pledge to pursue as long as I serve Teachers College. I ask you, the faculty, the students, staff, trustees, alumni and friends of Teachers College, to join me in making a real difference by getting a lot done. Just imagine: When TC's 20th president reflects on our legacy, she will refer to the early years of the 21st century, when Teachers College became the most consequential institution of its kind in the world. And she will feel the same pride and joy that I feel today.

Thank you, and good afternoon.

Published Friday, Feb. 2, 2007