At Beecher Hills Elementary School in Atlanta, they’re affectionately called the Roomies and the Zoomies — students who come to school and learn in classrooms, and peers who tune in on their home computer screens.

“All the children have headsets and headphones so they can hear and talk to each other,” says Beecher Hills Principal Crystal Jones, a 2018 member of TC’s Cahn Fellows Program for Distinguished Principals. [In spring 2021, the program separated from Teachers College under the name The Cahn Fellows Programs.] “Teachers are working hard to give equal engagement to both groups, but they’re understandably still anxious, because it’s a new skill. So, I’ve pulled from my Cahn knowledge and said, ‘It’s OK, we’re all learning this together. I’m not walking around with a pad to document what you’re doing wrong. We’re just doing our best for children.’”

That, in a nutshell, is the mindset that has enabled educators across America to persevere during an unprecedented time.

It was a year when:

COVID-19 infection rates rose and fell — and rose again, with a vengeance — keeping school communities in an ongoing state of whiplash.

Teachers’ unions across the nation threatened strikes if schools could not guarantee safe ventilation, social distancing and the wearing of masks.

The police killings of unarmed Black Americans dominated the headlines, creating fears and tensions in all schools, but especially those primarily serving students who are Black, Indigenous or people of color.

For months, the nation’s president contended that children are “almost immune” and that the virus would simply “go away.”

[Read a story in Education Week for a more detailed chronology of the year in schools.]

“This is truly the ultimate adaptive challenge for school leaders, because no one knows what’s going to happen, and because the sense of responsibility for other people is so heavy,” said Ellie Drago-Severson, Professor of Education Leadership and Adult Learning & Leadership and Director of the College’s Ph.D. Program in Education Leadership. “Many confide that they face overwhelming amounts of stress every day with no downtime or breaks.”

The experiences of alumni and other TC community members leading districts and schools tell the national story in microcosm.

In late March, as New York City’s schools went remote, Brett Schneider, founding Principal of Bronx Collaborative High School, was tasked with running his campus as a Regional Enrichment Center to serve children of health care providers, transit workers and other first responders to the pandemic. Under the direction of Schneider, a 2019 TC Cahn Fellow, the center recorded zero coronavirus infections.

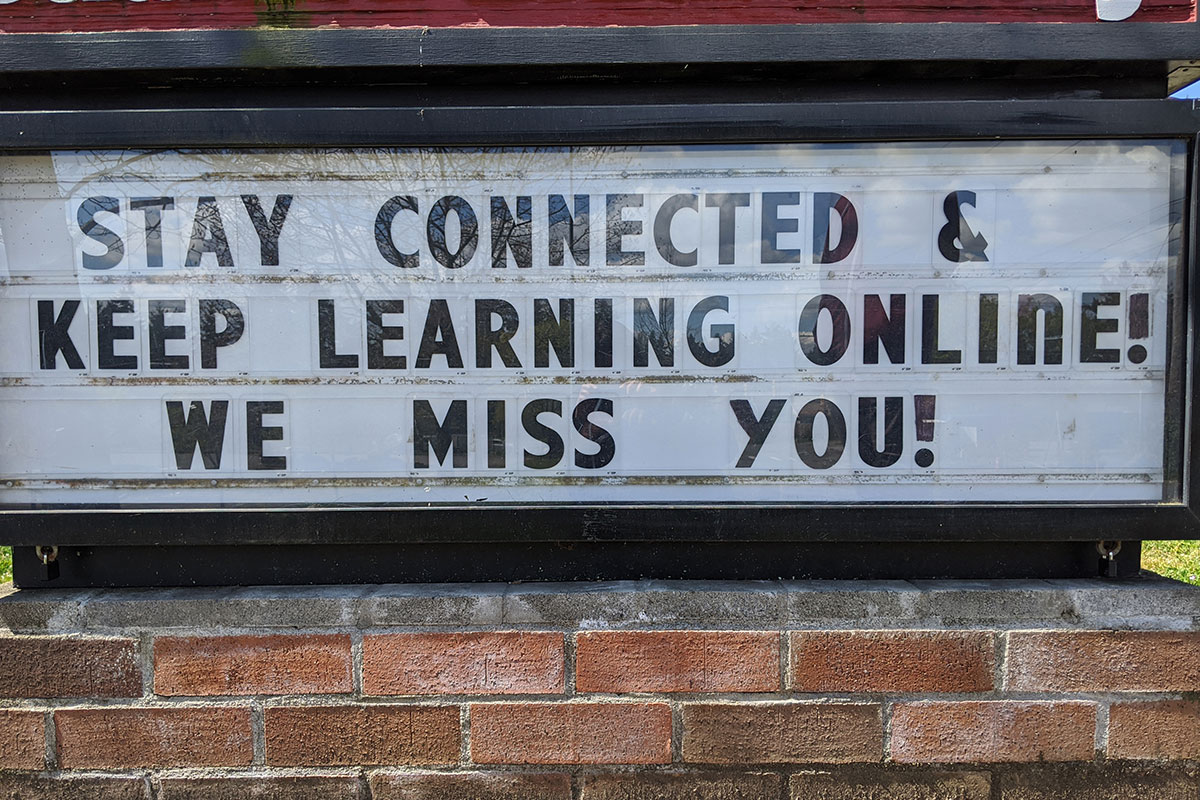

UNCERTAINTY HAS BEEN THE CONSTANT Schools closed, reopened, and closed again as COVID infection rates fluctuated. (Photo: iStock)

At Chicago’s Southside Occupational Academy High School, which serves special-needs students between the ages of 18–21, Principal and 2015 TC Cahn Fellow Joshua Long kept education as hands-on as possible. “Southside is about non-stop, human-to-human interaction,” he said in August. “A lot of my kids don’t talk and have other daily living and social-emotional needs, including autism, attention deficit disorders, depression and other cognitive impairments.”

Reached six months later, Long allowed that the transition online had been successful but had taken its toll. “Problem solving is part of a school leader’s DNA, and we typically do this pretty well. The difficult part was that the end-game was constantly redefined. I dream of the day when all of our students and staff are back in the building and switch classes when the bell rings.”

In Syosset, New York, Superintendent Thomas Rogers (Ed.D. ’06) said the biggest challenge has been “creating and staffing, in a matter of months, an entirely new virtual school system” — one the size of some entire neighboring school systems — that has operated in parallel with the “in-person” district, providing all the same services and meeting the same high expectations.

In Malverne, New York, Superintendent Lorna Lewis (Ed.D. ’92) devoted more than $1 million to personal protective equipment, cleaning supplies, protective barriers, cameras, iPads, temperature checking devices, foggers, weekly COVID testing on campus for the entire community and additional staffing to reduce class size. (One upside: “Our elementary school students are making significant gains thanks to improved personalized instruction.”)

“Flexibility and understanding” became the mantra for Katy Ho Weatherly (Ed.D. ’19, M.Ed. ’16), Music Manager for the District of Columbia Public Schools, where nearly 50,000 students were forced to leave their instruments in locked-down schools and quarantine at home — often with poor or non-existent access to the internet. Weatherly and her staff encouraged students to interview parents about the music that shaped their lives. Weatherly scoured the internet for music composition and performance sites and identified resources showing how to fashion musical instruments from household items. The district has shifted away from traditional music toward a focus on culturally relevant education, encouraging teachers to use the technology the district provides for songwriting and music production.

“The pandemic has been an opportunity to address our shortcomings, explore new pedagogies and, ultimately, to reimagine music education,” Weatherly said recently.

And in Teachers College’s own Hollingworth Preschool, Hollingworth Center Director Lisa Wright and her staff scrambled to offer children and their parents regular, online programming that included online science experiments, storytelling and musical performances, a guest owl wrangler (with owl) and a virtual field trip to the Mystic Aquariums.

“Preschool is a time for children to develop across all domains — social, emotional, physical and cognitive,” said Wright. “Birth to age five is a critical period of development. We can only build the foundation once.”

Indeed, the work of keeping school running has entailed far more than maintaining the academic side of the house. School psychologists have dealt with “the anxiety that goes along with uncertainty,” said Prerna Arora, Assistant Professor of School Psychology and Director of Teachers College’s School Mental Health for Minority Youth & Families (SMILE) Research Lab. “First it was: ‘What are things going to look like in the fall?’ But now it’s: ‘What are things going to look like next month, or even next week?’”

In Jackson, Mississippi, Midtown Public Charter School Principal Kevin Parkinson, a 2019 graduate of TC’s New Orleans-based Summer Principals Academy (SPA NOLA), focused on structure.

“One way we can provide emotional security for our students is to give them a routine, even in a digital world,” Parkinson said. “Part of that routine includes having cohorts with homeroom time. Just as if we were in-person, that includes really intentional ways that teachers can check in with students, whether that’s a mood meter or journal prompts. Then the teachers can alert other staff members to support kids when things are concerning.”

Yet flexibility has been equally important.

In the South San Francisco Unified School District, Aura Abing (M.Ed. ’12), who coordinates the district’s mental health programs and assessments, has worked to accommodate students with pre-existing psychological issues — including one 10th-grader with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) who was missing Zoom classes because he sometimes took an hour just to come downstairs from his room. “Kids with anxiety get really overwhelmed with all the pieces that are required and then get stuck,” Abing said. Solution: Letting the boy concentrate on his favorite activity: music and performance. “He was saying, ‘I have three or four classes I have to get to,’ and we said, ‘OK, let’s just focus on one.’”

But children haven’t been the only ones struggling.

“I believe a bigger challenge for us has been ensuring that our educators are in the right frame of mind to bring their best to work every day for our students,” said Libby Bonesteel (M.A. ’03), Superintendent of Vermont’s Montpelier-Roxbury Public Schools. “We have worked tirelessly to keep our staff positive and feeling good about what they are doing. They simply cannot do what they need to do for kids with any other mindset.”

And then there were issues that compelled entire school systems to rethink fundamental premises — for example, the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police, which launched protests across the country and around the world.

“So many young people of color being killed unnecessarily at the hands of police — it’s had an enormous impact on the psyche of our community,” said Camden, New Jersey, school superintendent Katrina McCombs (M.Ed. ’96), whose student population is half African American, half Latinx. “It really focused us on ensuring that we are building up our students’ resilience and their understanding that they are valued, despite what they may see happening in front of them.”

After Floyd’s death, Camden’s schools closed for a day of reflection. McCombs launched a review and revision of “our African American history courses and how we teach students who are Latinx about their backgrounds.” She called on the city to rename its Woodrow Wilson High School, both to disavow President Woodrow Wilson’s “segregationist practices and racist views” and to create “a learning experience for our students about how you can respond in a productive way to things happening in society that you’re not comfortable with.” Students of age received a refresher about their right to vote and how to exercise it, remotely or otherwise.

IN THE ATMOSPHERE Police violence against Black Americans has been part of the past year's stress, especially for students of color. (Photo: AP)

“We’ve provided tutorials, not delving into students’ political views, but making sure our families and students know how to obtain absentee ballots or whatever else might be a potential barrier for them.”

Amid the many wrenching trials, there also have been profoundly beautiful moments of hope.

In Malverne, Lorna Lewis reported a recent “weekend of joy” highlighted by a student performance of Guys and Dolls — “our very first ever digital production.

“I may be biased, but Broadway was alive here,” she said. “Our spring musical gave us evidence that we have risen to the occasion.”

And as 2021 began at Beecher Hills in Atlanta, Crystal Jones and her staff celebrated the return of the school’s youngest students (the “little people,” Jones calls them), some of whom had never set foot in school. It was a joyous moment, tempered by the reminder of time lost.

“There are skills that you can’t learn through a screen — how to write your name on a line on a piece of paper, opening a carton of milk yourself, reading directions — and people don’t think we teach those things in schools, but we do,” Jones said.

To counter the ongoing stress, Jones has started a book club for teachers and instituted schoolwide mindfulness sessions.

“We’re being very intentional about re-centering focus and making sure that everyone is calm and speaking positively,” she said. “Lots of positivity — in everything that we do.”