This story, "New Study Casts Doubts on Effectiveness of Personalized Learning Program in New Jersey" was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education and based at Teachers College, Columbia University.

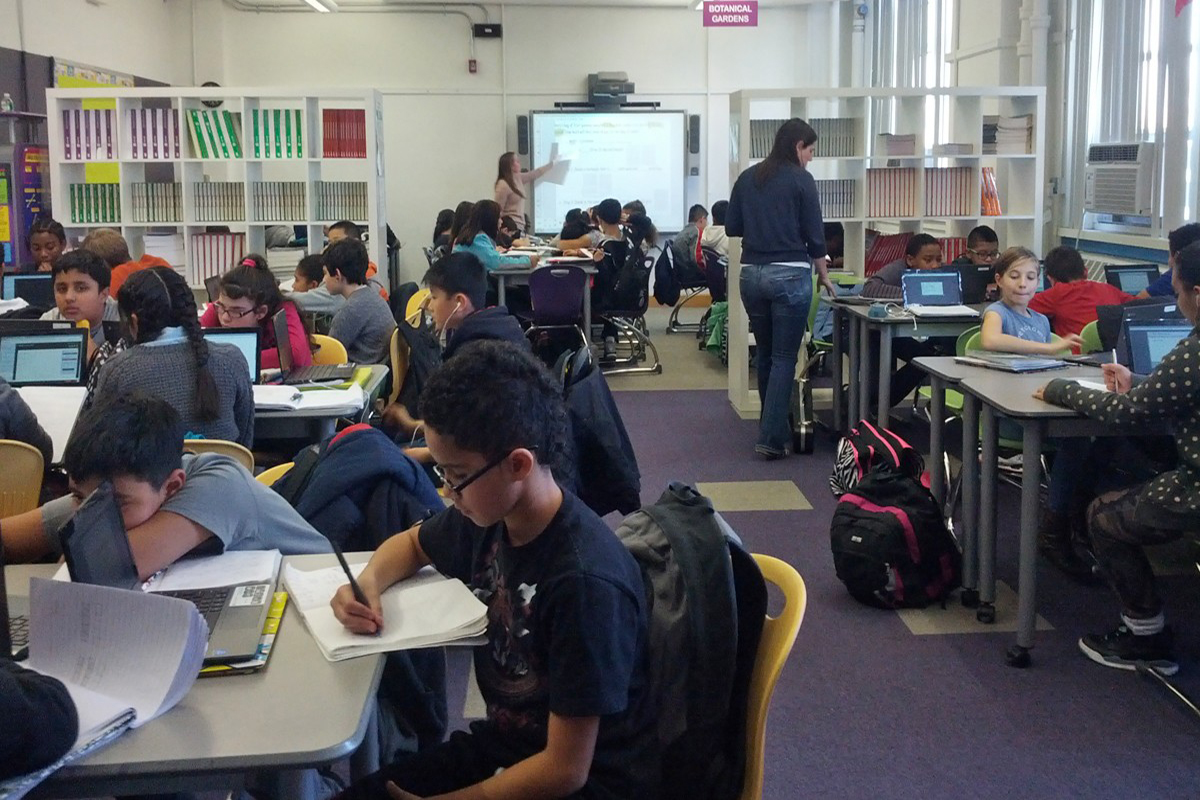

In the fall of 2015, five schools in the industrial port city of Elizabeth, New Jersey, dumped their usual math curriculum and started teaching their middle school students through a computerized system called “Teach to One.” It was an experiment in so-called “personalized learning,” where algorithms churned out customized lessons for each student. Many of the kids were behind their grade level and spent hours reviewing third-grade arithmetic while others could jump ahead to eighth-grade algebra.

But after three years of learning this way, the Teach to One students in grades six through eight scored no better on New Jersey’s annual math tests than other Elizabeth students who had learned math the usual way with the whole class on the same topic at the same time. “I can’t rule out that Teach to One had no effects” on student’s math achievement, said Doug Ready, a professor at Teachers College, Columbia University and lead author of a January 2019 study of the program.

The study highlights an ongoing conflict between personalized learning and the required annual tests that schools give to students. Joel Rose, the chief executive of the nonprofit organization that sells Teach to One to schools, is convinced that students who take the time to go back and master foundational concepts in math will be better off in the long run. “Math is cumulative,” he said. “You just can’t learn linear equations if you don’t know how to multiply.”

But the annual state tests that were used in this study don’t measure how much a student has caught up on things he or she should have learned years ago. For example, an 11-year-old student who jumped from third to fifth grade math in one year might still bomb the sixth-grade test and do no better than an equally weak student who was taught as usual with the sixth-grade curriculum.

“The study is unable to form any generalizable conclusions one way or the other” about Teach to One or personalized learning, said Rose. “There’s a real tension between an accountability system that emphasizes grade-level material and instructional models that meet kids where they are.”

The study, “Final Impact Results from the i3 Implementation of Teach to One: Math,” was financed by the U.S. Department of Education, which gives out grants to encourage schools to try educational innovations, such as Teach to One, and test their effectiveness. To win the grants, innovators agree to put their programs through a rigorous test with control groups of students who don’t get the intervention. The Teach to One study was conducted by an outside group, the Consortium for Policy Research in Education (CPRE), based at Teachers College, Columbia University. (The Hechinger Report is also based at Teachers College but is not affiliated with CPRE.)

Teach to One, whose origins date back a decade ago inside New York City’s Department of Education, has been one of the more prominent examples of personalized learning, an approach that is backed by a number of foundations, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (The Gates Foundation is also among the funders of The Hechinger Report.) Almost 40 schools and 10,000 students around the country are learning middle school math through Teach to One this 2018-19 school year, according to New Classrooms, the non-profit that now oversees the Teach to One curriculum.

At the same time, there’s been a backlash against this technology-driven instruction. Parents in a high-income community in Silicon Valley, California, complained that Teach to One minimized the role of the teacher and gave students an incoherent hodgepodge of worksheets from various publishers. Mountain View schools dropped the Teach to One curriculum in 2017. Only three of the five schools in the Elizabeth, New Jersey, study are sticking with it this year and paying for it with the school district’s own funds. Back in 2015, my colleague Nichole Dobo reported that nationally schools paid $225 per student plus between $50,000 and $125,000 a year for professional development and support services.

Teach to One’s aim is to use technology like a personal tutor, enabling struggling kids to catch up and advanced kids to surge ahead, improving everyone’s achievement. But the research evidence hasn’t been terribly strong. A study in 2012 by scholars at New York University of three middle schools that were earlier adopters of Teach to One in 2010-11 found mixed results. Those schools no longer use it. A 2015 study by a Columbia Business School professor looked at the expansion of Teach to One into more schools through 2014 and again that study didn’t find clear, positive benefits.

In this current January 2019 study, Ready looked at how Elizabeth students scored on the spring math test administered by the state. Those who had been taught by Teach to One were more likely to be disadvantaged and had slightly lower scores to start. But the annual changes in test scores over three years were relatively flat and quite similar for both students who had learned through Teach to One and those who hadn’t. (See Figure 1 on p. 11 of the study.) Even after adjusting for family income and other student characteristics, the students in the Teach to One classrooms didn’t improve more than students taught in the traditional way. In scientific speak, it was a “null” effect. Teach to One did neither harm nor good.

The authors cautioned against drawing too many conclusions about personalized learning or Teach to One from this one study. That’s because each of the five schools implemented the Teach to One program differently. Some schools requested more advanced grade-level content that would be on the state test. Other schools allowed middle-school students to methodically work through easier arithmetic. Regardless of these idiosyncrasies, none of the five schools demonstrated better performance than the control group of schools that didn’t use Teach to One. (See Figure 2 on p. 12 of the study. Only school “C “showed a dramatic test score improvement in the third year but the researchers said it should be ignored because it had been a port of entry school for new immigrants. In 2017 it stopped educating that low-achieving population. The new mix of students, wealthier and fluent in English, had higher test scores.)

Other studies without control groups have shown more positive test score gains for Teach to One. Ready, the lead author of the January 2019 study, also produced a 2014 study calculating that kids learning through Teach to One in more than a dozen schools around the country had achievement gains that were substantially larger than the national average. The students’ actual math scores weren’t higher than the national average; nearly all the Teach to One students were low income and many were low achieving. But students were tested throughout the year and the weakest students, in particular, had larger-than-average improvements during the year. By contrast, high achieving students didn’t soar.

When I contacted Teach to One to seek a reaction to this disappointing January 2019 study, CEO Rose sent me a rival study, financed by the Gates Foundation. Very similar to the 2014 study I describe in the previous paragraph, this February 2019 study by MarGrady Research also found that students who learned through Teach to One in 14 schools around the country had higher-than-average growth rates. The problem is that it doesn’t compare the gains of Teach to One students against the gains of similar students who didn’t learn that way. Indeed, the MarGrady report cautioned that you can’t conclude from this kind of analysis that Teach to One caused the students to improve in math. It also warned that national averages it used for comparison are imperfect because students in Teach to One schools are more likely to be poor, black and/or Latino than the average American student. Typically, weaker students show greater gains in percentage terms because even small gains are a larger share of a smaller base level.

Ideally, you’d want to know how much students in Elizabeth, New Jersey, learned during the year, both those that had Teach to One and those that didn’t. But that would require more testing throughout the year in addition to the mandatory spring state test and it’d be a tough sell to ask schools to add even more tests to the calendar.

— Jill Barshay