It started six summers ago as a teaching experiment inspired by the work of Ruth Vinz, TCs Enid & Lester Morse Professor in Teacher Education:

A group of about two dozen teachers and students converged at Teachers College for two weeks to reinterpret Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein as a multi-media performance for the stage.

[Read a story about CPET and its director, Roberta Lenger Kang.]

Since then the Literacy Unbound Summer Institute has become an annual highlight of TC’s Center for the Professional Education of Teachers (CPET), featuring similarly far-out re-conceptions of works such as The Metamorphosis (Franz Kafka), The Awakening (Kate Chopin), The Jungle (Upton Sinclair) and, most recently, Their Eyes Were Watching God (Zora Neale Hurston).

TEAM UNBOUND From left: Adele Bruni Ashley, Marcelle Mentor, Nathan Blom, Brian Veprek.

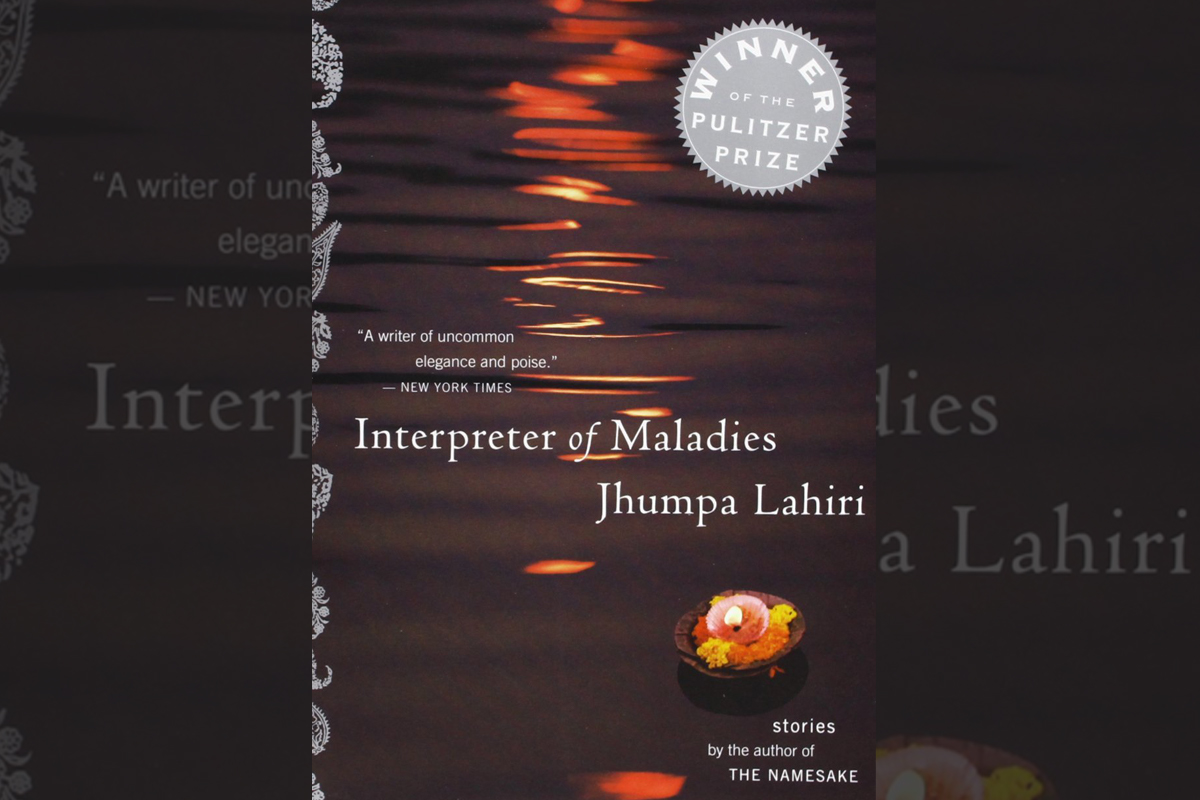

Alas, the COVID pandemic has made an in-person institute prohibitive this year. But the show will go on, albeit with some major departures from past iterations. The 2020 Summer Institute online workshops — led by Adele Bruni Ashley and Marcelle Mentor, both CPET Faculty Advisers and Lecturers in TC’s Teaching of English program; Nathan Blom, who recently earned his Ed.D. from the same program; and Brian Veprek, CPET Lead Professional Development Adviser — will build toward a “24-hour film challenge” in which workshop teams will have one day to produce short films inspired by Interpreter of Maladies, the Pulitzer Prize-winning short story collection by Jhumpa Lahiri. The nine stories in the collection touch on issues of grief, loss, separation and freedom through the prism of the immigrant South Asian immigrant and Native American experiences.

Our goal is to help form a visceral, emotional and intellectual connection to the text so that students 10 or 15 years after they attended the Institute will have an instantaneous reaction when they see the book they read because they know the text so deeply. My hope is that the text will always live in them.

—Adele Bruni Ashley

Guided by the Literacy Unbound staff, participants will begin workshopping passages from the Lahiri stories asynchronously at the start of July and then meet synchronously via a video platform with teaching artists in mid-July. The films will be screened, digitally, on Friday, July 31st.

Still, despite all the changes, some fundamental aspects of the institute remain the same.

“We invite them to make a connection,” says Veprek, a former theater major. “If a character feels alienation, we ask the students to reflect on a moment when they may have been alienated, put themselves in the character’s shoes and turn that into a form of creative expression.”

We invite them to make a connection. If a character feels alienation, we ask the students to reflect on a moment when they may have been alienated, put themselves in the character’s shoes and turn that into a form of creative expression.

—Brian Veprek

And, as Ashley points out, in one very real sense, the Literacy Unbound experience, though two weeks in duration, has never been constrained by time.

“Our goal is to help form a visceral, emotional and intellectual connection to the text so that students 10 or 15 years after they attended the Institute will have an instantaneous reaction when they see the book they read because they know the text so deeply,” she says. “My hope is that the text will always live in them.”

[Read a piece by Ashley about the Literacy Unbound experience.]

Ashley and Veprek envision the remote Summer Institute creating an opportunity for tips and mentoring from writers and artists who in other years can’t squeeze a visit to TC into their schedules.

Technology also opens up the possibility of expanding the workshop to students and teachers nationwide and overseas, including participation by the Singapore American school.

“We’re excited,” says Veprek. “It is uncharted territory.”

“I’m attached to in-person interaction in my mind,” adds Ashley, who holds an M.F.A. in Acting from the University of Washington. “But the whole point of fiction is to transport us into an imagined world. And that world transcends both digital space and physical space – because it is, after all, imagined.”