Ella Cara Deloria (B.S. ’1915), born on the South Dakota Yankton Indian Reservation, whose book Dakota Way of Life won the 2023 Dwight L. Smith (ABC-CLIO) Award and a bronze medal for the 2023 Will Rogers Medallion Award, is best known for her work recording oral histories and documenting the Dakota language, which paved the way for current Indigenous language preservation efforts. What is perhaps less known about Deloria, however, is her connection to TC and how her role as a teacher laid the foundation for her decades of work preserving and teaching the languages and culture of the Sioux, Lakota and Dakota tribes.

“[Deloria] was pushing the envelope of critical Indigenous scholarship at a time when nobody else was thinking about that or listening to that,” said TC’s Rachel Talbert, a Spencer Postdoctoral Fellow in the Curriculum and Teaching Department who co-curated a spring exhibition on Deloria for Gottesman Libraries and organized an event on the alum. “She was doing that work at a time when we were erasing native languages, and [it] prepared us for the time when you can teach that...Her practices, her way of teaching, they still impact so many things today and to think that she got her start at TC is humbling.”

Ella Cara Deloria’s commitment to cultural preservation and education began in her earliest schooling experiences at St. Elizabeth’s Mission School, which, contrary to other mission schools in the late 19th century, supported and encouraged Dakota people to learn their language and express their cultures. Her experiences at St. Elizabeth’s and All Saints School for Girls deepened Deloria’s love for learning and ultimately brought her to Teachers College in 1913, after two years at Oberlin.

(Photo courtesy of Dr. Phillip Deloria)

A contemporary of John Dewey and Georgia O’Keeffe, by the time Deloria completed her undergraduate studies two years later, she was already leveraging her cultural knowledge to help push the field of anthropology forward. In her final semester, Deloria met Franz Boas, Columbia University professor and the father of modern anthropology, and was hired to help teach Lakota — a language mutually intelligible with Dakota — to his university linguistics students. While this experience was Deloria’s first foray into the formal study of Indigenous language and culture, it would be more than a decade before she began her career as an anthropologist and ethnographer.

With the foundation provided by her TC education, Deloria spent 13 years deeply involved in the education of Native Americans, a necessary aspect of cultural preservation. “When you preserve a culture, when you preserve a language, there's no really other way to go about that than to teach it,” said Kianna Pete (M.A. ’25), a Diné/Navajo education policy researcher who spent two years curating the Gottesman Libraries spring exhibition with Talbert. “It was essential to ensure that her own people would know their languages and cultures.”

Deloria taught at both her alma maters, then spent five years supervising health education in Indian Schools for the YWCA and finally, worked as a dance and physical education teacher at Haskell Indian school in Lawrence, Kansas until 1927. She then reconnected with Boas and began her ethnographic work in earnest. She went from piecework translator to published author in less than two years, producing “The Sun Dance of the Oglala Sioux,” a translation and analysis of a text describing an important Lakota religious ceremony, in the Journal of American Folklore in 1929.

Over the next five decades, with the support of various federal grants, including a grant from the National Science Foundation, she conducted fieldwork on Sioux and Navajo lands, produced eight books including Dakota Texts (1932) and Waterlily (2009) among other academic publications, wrote several religious pageants, worked on a Dakota language dictionary, held positions at the Sioux Indian Museum and W. H. Over Museum and continued teaching while also supporting her sister and caring for her ailing father.

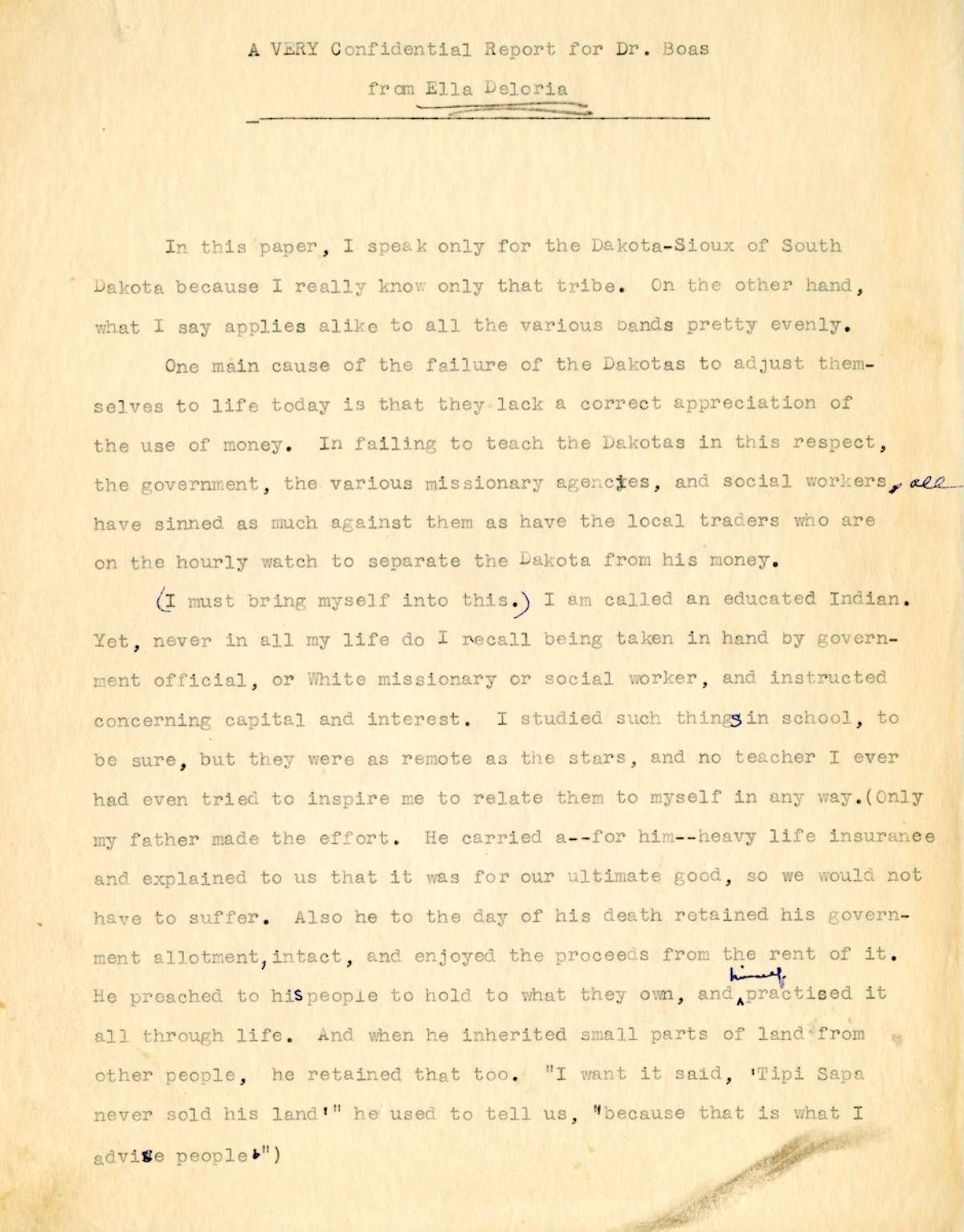

The first page of Ella Cara Deloria's 10-page report to Franz Boas. (Credit: American Philosophical Society)

Her experiences studying and teaching Indigenous culture, particularly Dakota culture, led Deloria to interrogate the myriad ways education was failing Indigenous people. She outlined these concerns — which ranged from a lack of a practical education to risks of cultural erasure — in an impassioned report to Franz Boas. Many of the observations she made in the report to Boas were reflected in Deloria’s life, particularly when it came to finances.

Even as she was doing invaluable ethnographic work and teaching future generations, Deloria struggled financially throughout her entire adult life. She relied on the support of her father and brother when she could but by 1935, in the midst of the Great Depression, Deloria was supporting herself, her sister, and her relatives while living in her car.

“[She faced] complex challenges of culture and personality, of history and structure and of poverty and obligation, even as she created the extraordinary body of the scholarship,” said Philip J. Deloria, the scholar’s nephew during his remarks at the event for Ella Cara Deloria. “She was here [at TC] but she could not access, to the same extent, the resources that powered the careers of other Boasian anthropologists. [But] At the same time, when she returned to South Dakota, with her salary and an expense account, Ella herself was a major conduit of resources.”

Just as her philosophy on anthropology and Indigenous education still rings true today, so too does her struggle for financial stability, especially in the wake of funding cuts for researchers.

Researchers still make sacrifices to conduct their work, says Pete. “It follows the narrative [that] people have been here before. There's always this overlying hope that exists beyond the financial aspect that keeps people going.”

Deloria’s tenacity to produce excellent work under difficult circumstances serves as an inspiration of sorts for many scholars including Talbert. “It's awful that Ella Cara lived with that precarity. [But] it only makes me think that she shines even brighter, because she did that work without access to basic things like food, translating equipment, all the things that we take for granted now,” says Talbert, who has helped develop a Lenape curriculum for NYC schools. “We should continue to be learning about Ella Cara Deloria's legacy and doing all we can to [support] Indigenous students to do the kinds of work they want to do for Indigenous futurity.”