Not long ago, Kenny Graves was a self-described technology geek with a cool job title and academic interests that were beyond most people’s comprehension.

Now, very arguably, Graves (Ph.D. ’19) – who will take up new duties on July 1st as Assistant Principal for Academic Life & Director of Studies at New York City’s elite Ethical Culture Fieldston School, overseeing academic programs for grades 9-12 — represents the future of K-12 education.

Graves, whose previous title at Fieldston was Upper School Ethics and Technology Coordinator, hasn’t changed. Rather, the world has — and suddenly the issues he probed in his award-winning TC doctoral thesis have moved from the relative fringes of the education world to become matters of basic survival in both the long and short term.

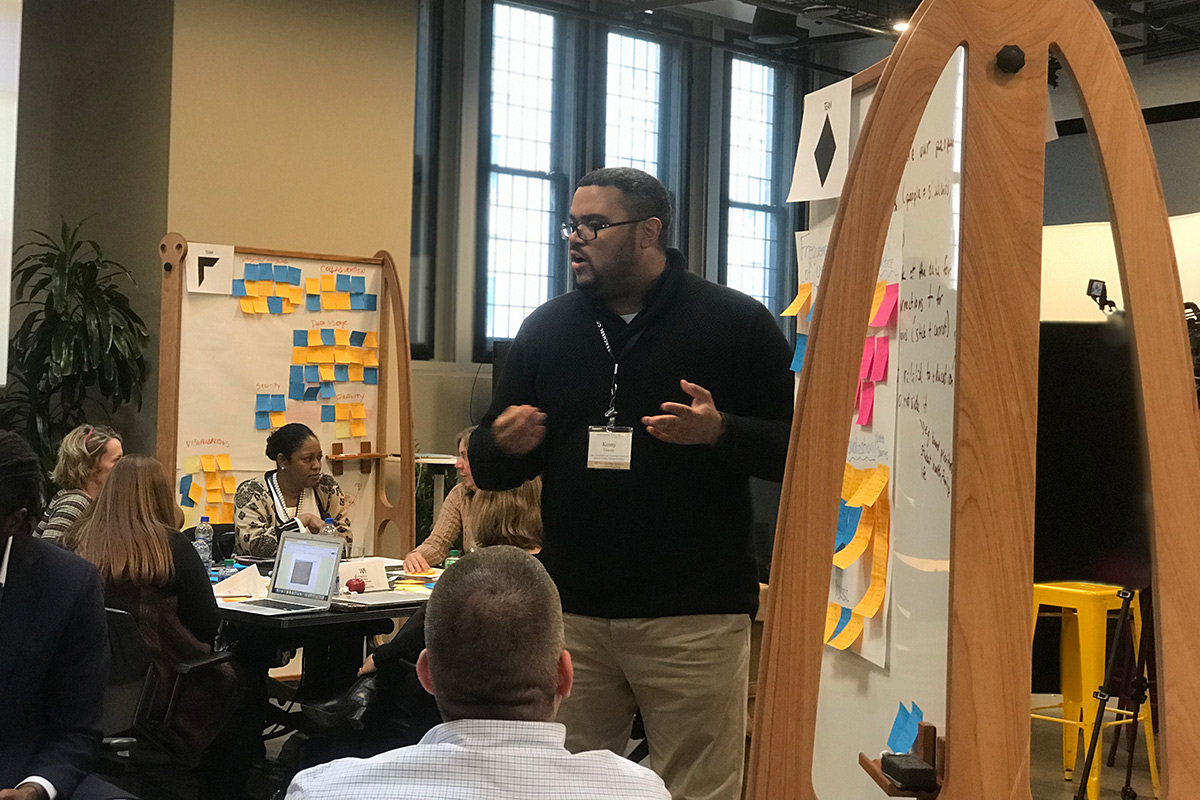

BRIDGING A DIFFERENT DIVIDE, TOO Graves at a recent TC conference that brought together data scientists and K-12 educators. (Photo by Alex Bowers)

“In forcing schools to move to remote learning, the COVID crisis has pulled the world out from underneath teachers, thrusting them into a totally new learning environment,” says Graves, who also serves as an adjunct professor at TC’s Klingenstein Center for Independent School Leadership. “Technology coordinators traditionally played in the background. We helped teachers with technology, but for the most part we were called as needed. Now, technologists are almost running their schools. They are not just leading the conversation about logistics and scheduling, but also about instruction, how kids are learning, and many of the ethical and social justice implications that arise with technology.”

That’s certainly been the case at Fieldston, where — under Upper School Principal Nigel Furlonge (M.Ed. ’06), another TC Education Leadership program alumnus — Graves was part of a talented team of technologists that were the guiding force in a phased transition to distance learning that began in mid-March. During the first week, faculty taught asynchronously, posting course content for students to work on individually rather than teaching cohorts in real time. During week two, the school blended asynchronous instruction, group learning and one-on-one teacher-student consultation. By week three, teachers were convening classes online.

Technology coordinators traditionally played in the background. We helped teachers with technology, but for the most part we were called as needed. Now, technologists are almost running their schools. They are not just leading the conversation about logistics and scheduling, but also about instruction, how kids are learning, and many of the ethical and social justice implications that arise with technology.

— Kenny Graves (Ph.D. '19)

Throughout that time, and since, Graves has counseled faculty to avoid a top-down approach and instead use technology as a tool for “student-centered learning,” in particular by avoiding “the comfort zone of lecturing.”

“If you connect to your students in person, then I’ll guarantee you will connect to them online,” he says. “Flexibility, creativity and all the intangibles that contribute to good teaching are just as applicable in this environment. Without being mindful of those qualities, you are going to struggle as a teacher under any circumstances.”

That perspective reflects Graves’ experiences as both a student and teacher. Growing up in suburban Maryland, he enjoyed taking computers apart and reassembling them, but his school offered few technology courses. Sparked by a teacher who turned him on to writers such as Toni Morrison and James Baldwin, he went on to study English and education at the University of Richmond. After teaching in a public school that provided its students with laptops but offered no guidance on how to best make use of them, he decided education was missing a major bet, and went in search of a graduate program that would give him the tools to bring about change.

At TC, where he earned his doctorate in Education Leadership, Graves concentrated his research on the connection between teacher technology use, school leadership and student achievement within historically underrepresented communities. He worked with faculty such as Alex Bowers, who draws on methods from cancer research to identify data useful to superintendents and principals; Mark Gooden, whose work focuses on culturally responsive and anti-racist school leadership; Sonya Douglass Horsford, who examines the problem of racial inequality in K-12 schools and how race is conceptualized and understood by leaders for equity and social justice in the United States; and Ellen Meier, a champion for meaningful technology integration in schools.

“Kenny’s work is at the intersection of integrating technology and innovation, teaching, student empowerment, leadership and data science,” says Bowers, with whom Graves co-facilitated two major conferences on data analytics in education leadership held at TC during 2018 and 2019. “Through his research, he has shown that there are very different types of technology use in school which have deep implications for not only student learning and school instructional improvement, but also in addressing longstanding issues of inequities in education, especially when considering the digital divide. But what I also deeply respect in his work is that he’s a collaborative, kind, and thoughtful leader who is equally talented in working closely with students, teachers, and school leaders on addressing these issues on the ground in their work in schools.”

Kenny’s work is at the intersection of integrating technology and innovation, teaching, student empowerment, leadership and data science.

— Alex Bowers, Associate Professor of Education Leadership

In 2016, the American Educational Research Association awarded Graves a $20,000 Dissertation Grant, and this past spring the AERA’s Advanced Studies of National Databases Special Interest Group honored his project — three related articles collectively titled “Disrupting the Digital Norm in the New Digital Divide: Toward a Conceptual and Empirical Framework of Technology Leadership for Social Justice Through Multilevel Latent Class Analysis” — as the Dissertation of the Year. In the first article, Graves analyzes data from a 2009 national survey to group teachers into four categories according to their use of technology (Dexterous, Presenters, Assessors, and Evaders). He finds that teachers in low-income schools are more likely to be in the teacher subgroups that use technology in less impactful ways in the classroom. In the second article, in an analysis of data from a 2011-12 study of teachers in Texas, Graves finds that teachers with the lowest perceptions of technology leadership had the lowest student achievement outcomes and were more likely to serve students from historically minoritized backgrounds. And in the third paper, based on a meta-narrative literature review of 60 studies that examine culturally responsive technology leadership practices within schools and districts, Graves called for school leaders and policy makers to use educational technology as “a vehicle for educational equality that could include improving resource allocation, democratizing decision making, and positively impacting student outcomes… investing in professional development to improve the disparity in how teachers use technology, and preparing leaders to utilize culturally responsive approaches to leadership to support their technology leadership efforts.”

Current circumstances would seem to argue that education leaders everywhere would be wise to take that advice. Schools could still be working largely online come fall, but beyond the dictates of COVID, there is a broader sense that the genie is out of the bottle when it comes to technology. Even as some teachers have struggled, others have discovered the potential of the digital medium to enable new kinds of individualized instruction and group collaboration, and to give young learners more agency in driving the learning process. With the nation acutely focused on racial equity, schools will be under even more pressure to provide all students with equal access not only to technology, but also to teachers who know how to use it.

“It will take time and also professional development. There’s a battle against inequality in the digital and online realm that everyone – from teachers, school leaders, parents, and most of all, students – should work to recognize, educate themselves, and take action to fix.” Graves acknowledges.

But strides are being made. Graves recalls that several years ago, when he was a public teacher, his students, most of whom were of color, were surprised to have a technology-loving teacher who “looked like them.”

Now, as Ethical Culture Fieldston School has discovered, there’s a model for the kind of person who not only can lead the development of technology in K-12 schools, but center it in the mainstream of academic programming. Regardless of race or gender, that person looks a lot like Kenny Graves.

— Steve Giegerich