This story, “Luring Covid-Cautious Parents Back to School,” was originally published on March 19, 2022, by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education and based at Teachers College, Columbia University.

LANHAM, Md. – Close to 700 days after her youngest children last set foot in a school classroom, Monica Rodriguez faced a decision she dreaded: Should she let them return to in-person learning?

For months, her youngest, Daniel Lewis-Coleman, a fourth grader, started his school days just as he had in March 2020, perched at a small table in the family’s kitchen. Steps away, his older brother, David Spriggs, 14, spread his work out on the dining room table. Tiny security cameras mounted throughout their home allowed Rodriguez to monitor her children to make sure they were at their Chromebooks during school hours, not wandering the house or surfing the web.

“[Daniel] being in virtual learning and my eighth grader being in virtual learning is a blessing,” Rodriguez said. The virtual option was particularly helpful for her older son. “There’s no one around to distract him,” Rodriguez said.

“Those students who aren’t progressing — give them the opportunity to go back to school if that’s what their parents want,” she added. “My children are just fine.”

Rodriguez is among thousands of American parents who were happy with remote learning as the Covid-19 pandemic ebbed and flowed — or, if not happy, at least willing to put up with virtual classes rather than send their children to school buildings where their safety was less assured than at home.

The push to return to a pre-pandemic normal put those parents resolve to the test. Many districts ended hybrid and virtual options during the fall, and more recently mask requirements have ended in even the most Covid-cautious places, like New York and New Jersey, after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention loosened its mask restrictions in February.

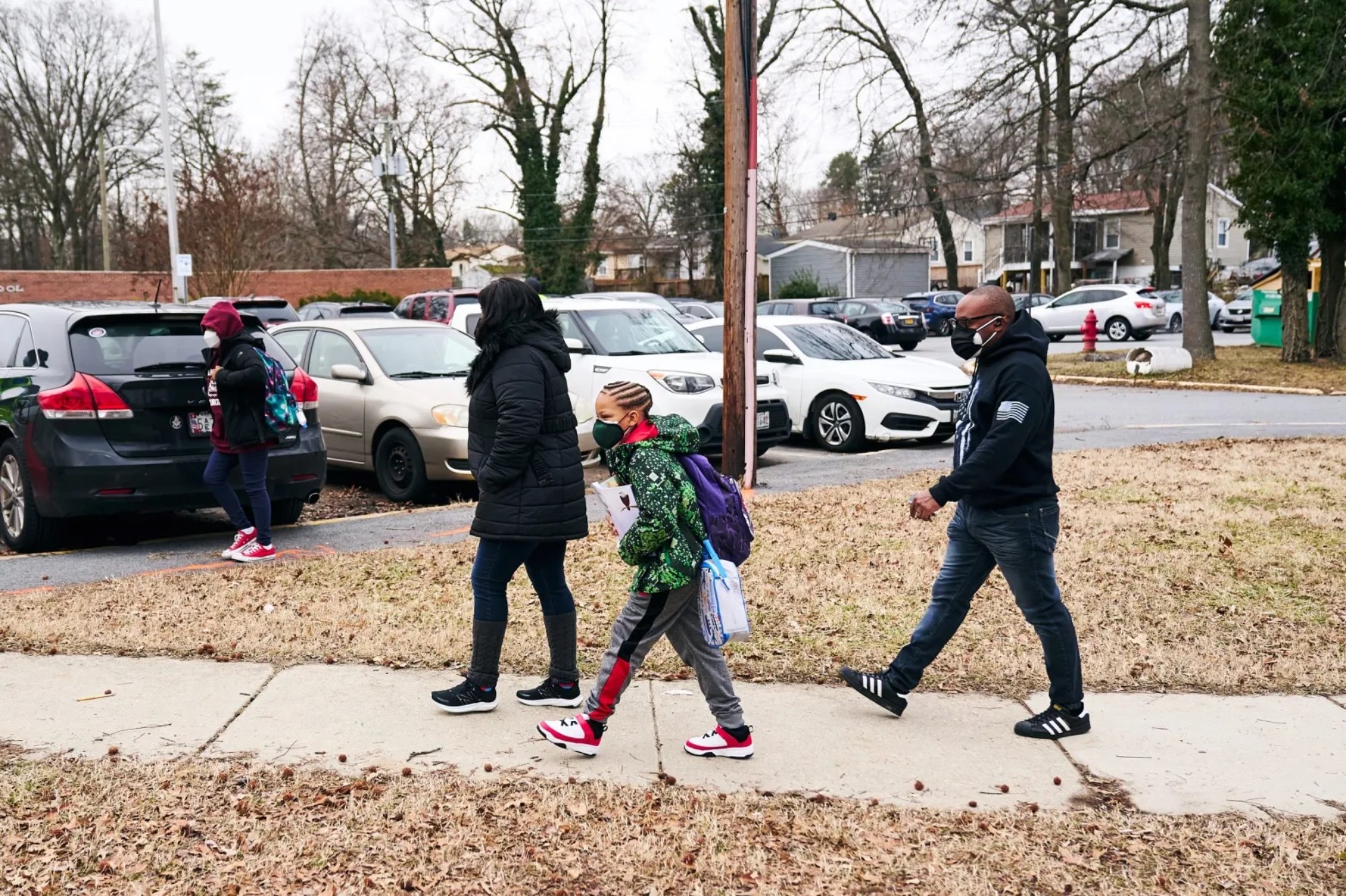

After days of soul-searching, Monica Rodriguez decided to return her son, Daniel Lewis-Coleman, a 9-year-old fourth grader, to in-person learning at Prince George’s County schools. Her family, including her husband, David Rodriguez, suffered through a bout of Covid-19 in late 2021. (Photo: Noah Willman/The Hechinger Report)

Perhaps nowhere has the shift back to normal been more jarring than in Prince George’s County Public Schools in Maryland. Though not its original intent, the district set up a massive virtual learning experiment when, in order to placate anxious parents, it extended enrollment in its remote program for K-6 students during last summer’s delta variant surge. Thousands of families decided to choose that option, which the district said would last only for the first semester, when a pediatric vaccine was expected to be approved.

While enrollment fluctuated, as many as 12,000 elementary students, or 18 percent of the district’s kindergarten through sixth grade enrollment, were enrolled in virtual learning — many, like Daniel and David, since the pandemic’s early days. By the time the K-6 virtual program ended Jan. 28, a little over 10,000 students were still enrolled.

That large virtual program made the county an outlier both in Maryland and nationally. As of this past December, 44 percent of the remote learners in the state were in Prince George’s County, according to state figures. And of the 100 large urban districts that are being tracked by the Center for Reinventing Public Education, only Hawaii, with about 10,000 remote learners in all grades, had a similarly sized virtual enrollment, said Bree Dusseault, principal research analyst at the center.

Black and Latino parents were more likely than parents of other races and ethnicities to fear for their children’s health during in-person learning. Prince George’s County, a district of 130,000 students in suburban Washington, D.C. has a student population that is 55 percent Black and 36 percent Latino. Among virtual learners in the district, 60 percent were Black and 30 percent were Latino.

When the district reminded parents that the program would end this January — just as omicron was sweeping the nation — parents here dissented loudly.

The battle over remote learning in Prince George’s highlights the precarious situation districts find themselves in when it comes to keeping parents happy, where any choice is likely to cause anger and parental defections. In some cases, school leaders have lost their jobs. Large numbers of cautious parents still don’t believe that public school is a safe place for their children during the pandemic. Some have found other options such as homeschooling, which has seen a significant increase, particularly among Black families. Prince George’s County has seen student enrollment drop by about 7,000 students since the fall of 2019, which matches national trends, although it is at the high end of the range.

What can districts do to rebuild trust with families? This question is even more pressing as a new subvariant of omicron, BA.2, has started to spread, potentially setting off another wave of parental anxiety. But the experience in Prince George’s County suggests that getting children back in seats may just be a matter of eliminating any alternative.

Vladimir Kogan, an associate professor of political science at Ohio State University, said that parents become more willing to send their children to school when districts are open for full-time, in-person instruction — and remove other options. The continuing reluctance represents a broader failure to explain risks clearly to parents, including the risks of missing in-person school.

“The parents who are demanding the virtual options — I don’t think that’s a reasonable position at this point to have, and it’s been a societal failure of risk communication. Parents don’t get to withhold education from their kids, just like parents don’t get to withhold food or medical care,” Kogan said.

“We have normalized something that before the pandemic seemed crazy,” he added, “which is that parent anxiety is a justification to opt out of compulsory education.”

Prince George’s County, like most school districts in the country, lurched into fully-remote school two years ago to slow the spread of Covid-19. This school year was supposed to be a return to something like normal.

“Nothing can replace that special dynamic that occurs when students and teachers are together in a classroom,” said district CEO Monica Goldson, in a recorded message to parents.

The remote option was scheduled to end in January, just as the omicron variant started to spike. To make matters even more complicated, Prince George’s chose to keep all its students out of school and in remote learning for an extra two weeks after winter break, in an attempt to slow the spread of omicron.

The large enrollment in the temporary K-6 virtual learning program made it clear that, for many, this school year was no time to return to business as usual. (Elsewhere, in places where district-run virtual options weren’t offered, parents found alternatives: Enrollment in virtual charter schools was already growing quickly before the pandemic, and the disruptions accelerated that trend.)

“It irritated me to my core,” Rodriguez said. Two weeks was not enough time to break the spread of the virus, she said, and why was the district still moving ahead with its plan to bring remote elementary school students back, while at the same time saying that students needed to be out of school temporarily?

Other Prince George’s parents also wanted to see virtual learning remain. Danielle Wood, whose son is in fifth grade, said she collected 1,500 signatures on a petition to keep the choice of virtual learning in the district for the rest of this school year, and also organized a small but noisy caravan of parents to circle school board headquarters, honking in support of remote school.

Wood’s son connected with his class via Zoom, and was an honor student last year, she said. And better yet, the family was able to keep Covid out of their household.

“We still quarantine. We never gave up, we never gave in. Why do we have to?” Wood said. “His family has been completely Covid-free and now there’s this constant fear and a high possibility of getting Covid.”

New research is starting to dig into the roots what kind of work and messaging districts can do to address parent concerns about school safety.

Sonya Douglass Horsford, a professor of educational leadership at Teachers College, Columbia University, and the founding director of the Black Education Research Collective, has examined the response of Black parents to the pandemic and to other recent stressors, such as the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020. (The Hechinger Report is an independent media organization based at Teachers College.)

Sonya Douglass Horsford, Professor of Education Leadership. (Photo: TC Archives)

Through surveys and focus group interviews, the collective’s report found that the pandemic “just kind of exposed in an explosive way how far away schools are from what Black parents really want,” Horsford said.

“Parents are thinking it’s not worth it to me to just go along with a system that may not be there to support the safety and wellness of our children. Districts need to respect that. The question then becomes what do we do with this information? Are we going to keep learning from this, or are we just going to go back to what we’ve done?” She said districts need to embrace more systemic changes to address these families’ concerns.

Another recent study showed that a text message outlining both safety procedures and the importance of in-person learning can be a relatively simple way for districts to build trust among wavering parents. After receiving that message, more parents said they were willing to return their child to school.

Messages about the value of in-person learning are important, because studies suggest that the pandemic was far from an ideal way to implement effective remote learning. A Maryland Department of Education report from January noted that in nearly all of its districts, across all grades and subjects, the failure rate was nine percentage points higher for virtual students than for in-person students.

In Prince George’s County, the academic performance of remote versus in-person learners was mixed. County-provided data shows that in-person students performed slightly better in English Language Arts on the Maryland Comprehensive Assessment Program administered last fall: 24 percent met or exceeded expectations, compared to 21 percent of remote learners.

But in math, 5 percent of in-person students met or exceeded expectations, compared to 11 percent of remote students.

Monica Rodriguez, her 9-year-old son, Daniel Lewis-Coleman, and husband, David Rodriguez, head to Daniel’s first day of in-person learning since March 2020 at James McHenry Elementary in Lanham, Md. (Photo: Noah Willman/The Hechinger Report)

Even in their protective bubble, Monica Rodriguez’s household was hit hard by the coronavirus in late December 2021. Both children lost their appetites and spent a few days in bed; Rodriguez said she still suffers from aches and an occasional racking cough. But Rodriguez’s mother, who lives in the home and has heart and lung disease, escaped unscathed.

Rather than bringing relief, the experience made had made Rodriguez even more determined to limit her family’s exposure to a virus that she said is changing too fast for experts to track.

But as the deadline to return to school came close, Rodriguez said she was worried that her children’s grades would slip if she taught them at home. Private online school also didn’t seem to be the right fit.

Ultimately, it was her trust in her son’s teachers, and the other educators in the building, that convinced Rodriguez to return her fourth grader to in-person school.

“It wasn’t so much what they said, it was what they did,” Rodriguez said. “And it went from the principal and the staff as well. Nobody wanted to be in person, in my opinion. But the fact that they’re in the building, they’re at risk just like my child. They’re going to do everything they can to make sure they’re safe, so that in turn spills over to my child. He’s going to be as safe as possible as well.”

Still, her soul-searching took some time; Daniel ended up returning to school Feb. 7, a week after the virtual K-6 program ended and most other students returned. David, her eighth grader, has remained a remote learner; Prince George’s school officials said that enough older students thrived during virtual learning to make it a permanent option for students in grades 7-12.

After 693 days out of school, preparing for the first day back was a whirlwind. Rodriguez packed Daniel’s lunch, made sure his double masks were securely in place, and tucked Lysol wipes in his backpack.

“Be the awesome Daniel Tiger that your teachers are accustomed to,” Rodriguez told her son.

In the end, the vast majority of virtual learners — over 90 percent — returned to brick-and-mortar schools. A district spokeswoman said that soon after the K-6 program ended, 633 students withdrew from the district, and another 130 were unaccounted for.

Rodriguez said she felt comfortable, though resigned.

“There’s no guarantee that he’s not going to come in contact with someone with Covid,” she said. “I’ve had to have those conversations, in talking with his principal, that when my son is at school, he is the most important person there. I need you to understand, the same way I’m the squeaky wheel about his education? I’m going to be on you guys about his safety.”