Editor’s Note: This article was updated on November 15, 2023, and December 6, 2023, to correct a previous version of this story that did not cite the work of Crystal R. Sanders, Associate Professor of African American Studies at Emory University, who coined the term “segregation scholarships,” which were created by southern states to fund the study by Black students at northern higher education institutions with the purpose of maintaining segregation in the South. The previous version also erroneously identified TC alumna Jane Ellen McAllister and TC’s earliest Black students as recipients of such scholarships, though these programs were not created until later.

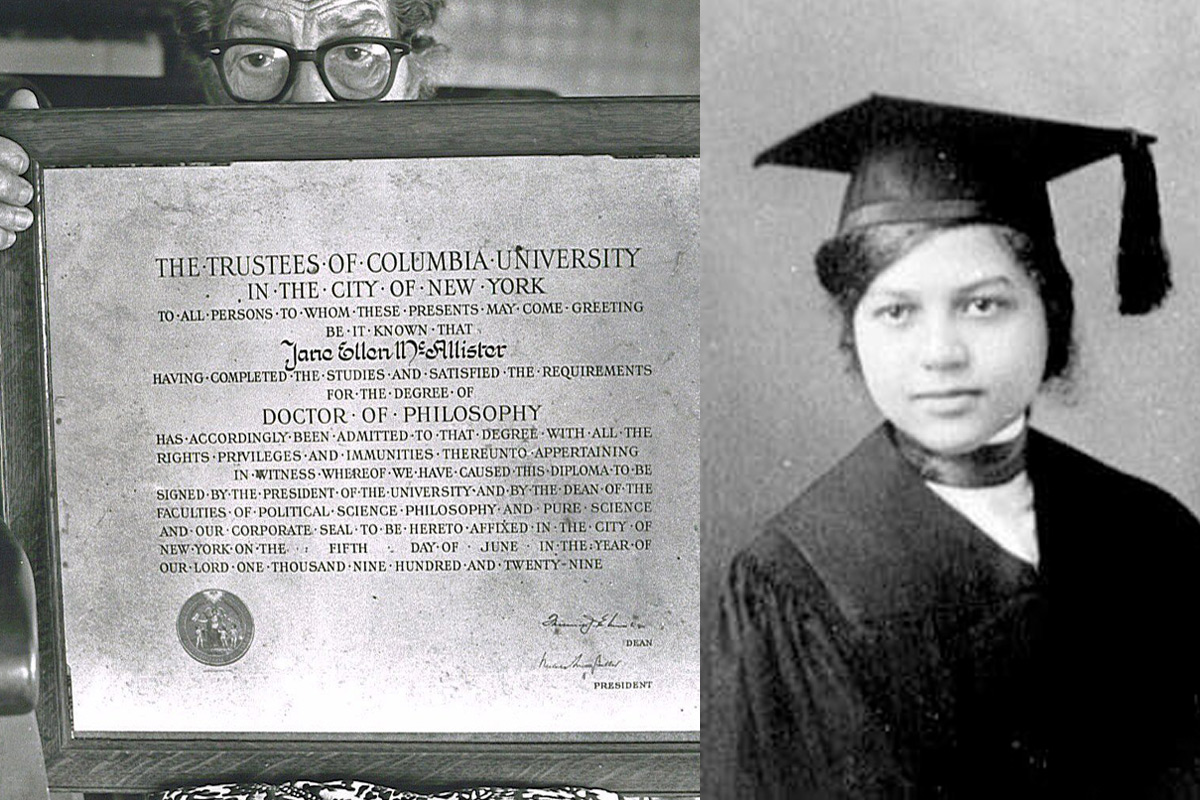

Forty-four miles outside of Jackson, Mississippi, a large green plaque stands tall outside of the former home of TC alumna Jane Ellen McAllister — the first Black woman to earn a doctorate in education in 1929.

Nearly 100 years later, McAllister’s trailblazing career is set to be celebrated in a forthcoming museum that will further crystallize the historical role of her 40-year career teaching and improving education outcomes for Black people.

Vicksburg, Miss., citizens at the unveiling of a marker in honor of TC alumna Jane Ellen McAllister in 2019. (Photo: The Vicksburg Post)

“One of her sayings was that ‘Poorly prepared teachers teach poorly prepared students to become poorly prepared teachers,’” remembers cousin Bettye Gardner. “And that’s why she ultimately chose to go to Teachers College.”

McAllister’s path to Teachers College from the Jim Crow-era South — ruled by “separate-but-equal” laws that codified discrimination after the Civil War — was not an uncommon one.

She was one of an unknown number of Black students who came to TC and other northern schools to pursue graduate studies at a time when southern institutions remained segregated. Later, Southern states would offer what Emory professor Crystal Sanders has called “segregation scholarships” (Sanders, 2024). While the earliest Black students at TC preceded these programs, later attendees from across the South did receive state assistance to offset the cost of attendance. Once on campus, they quickly realized that systemic racism and bigotry did not end at the Mason-Dixon line and continued to persist. In the words of 2019 Edmund W. Gordon lecturer Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings, such myths about a perfect, non-bigoted North were simply “a vision of America that doesn’t exist.”

While McAllister and her TC contemporaries went north, others attended Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) — which promised robust experiences for students that W.E.B. Du Bois said would “prepare broadly educated Black students to assume their rightful places as full, co-equal citizens in America and the world.”

TC — explained Professor Emerita of History & Education Cally Waite — would develop close ties with HBCUs through the development of summer certificate programs that would train even more educators, many of whom would return to HBCUs and go on to lead their own schools.

“The HBCUs all followed the same curriculum in teaching their own teachers, so the influence of Teachers College — people don’t realize — spread far and wide,” said Waite, whose work focused on the history of Black education, in 2014.

Meanwhile, some students took discriminatory practices to court, with few yielding success against states with deep racism embedded at multiple levels of government. But it wasn’t until the ruling of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and finally the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that American education could offer a more equal — but still deeply inequitable and flawed — future for all of its students.

“Living without bitterness is not easy,” McAllister once said, “but education, not fighting, is the only way out of poverty, bias and ignorance.”