A legendary era of creative energy for Black Americans, the Harlem Renaissance was a bright spot of art and activism, though its participants were still battling 20th-century racism. Now, the Metropolitan Museum of Art honors this period in their new exhibition, “Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism,” featuring more than 160 works of art from major Harlem Renaissance contributors, including TC alumni, Charles Alston (M.A. ’31) and Aaron Douglas (M.A. ’44). Both prolific artists whose work influenced Black American art for generations to come, Alston and Douglas also dedicated years of their lives to educating future artists.

The exhibition is only the second time in its history that the Metropolitan Museum of Art has emphasized the contributions of Black American artists with a dedicated exhibition. And it’s the first time in the museum’s 150 year history where the art itself — rather than other historical materials — is actually on display. The fact that this exhibition is a first showcases that we still have much to learn about the Harlem Renaissance and its century-long impact.

(Photo: iStock)

Why the Harlem Renaissance Is Still Relevant Today

“At a time where things are being banned left and right, in a society where we're fighting for fair education, equity, social justice, diversity and inclusion, we can really learn from the contributions of the Harlem Renaissance,” says Honey Walrond (Ed.M. ’21), a current TC doctoral fellow whose scholarship at the Edmund W. Gordon Institute for Urban and Minority Education and background intersect with the history.

Spanning roughly 20 years from the start of the Great Migration through World War II, the Harlem Renaissance is an oft-explored era of history. In Walrond’s view, by using culturally-relevant pedagogies and focusing on lesser-known contributors, there’s a potential to both acknowledge a deeply influential period of time while centering local histories, a rewarding journey made even more special by how many Harlem Renaissance artists attended TC. “There's so much literature, so much art, so much music [from that time period] that we, as researchers, can tap into to bring out the humanity in our research,” says Walrond.

Many schools today do include this important period in Black history in their English and Social Studies curricula. “While recognizing the Harlem Renaissance’s importance, we also should teach other important themes in Black history, other important moments in Harlem's history,” shares Ansley Erickson, Associate Professor of History and Education, whose work focuses on how educators can integrate Harlem history and civil rights history into their curriculum.

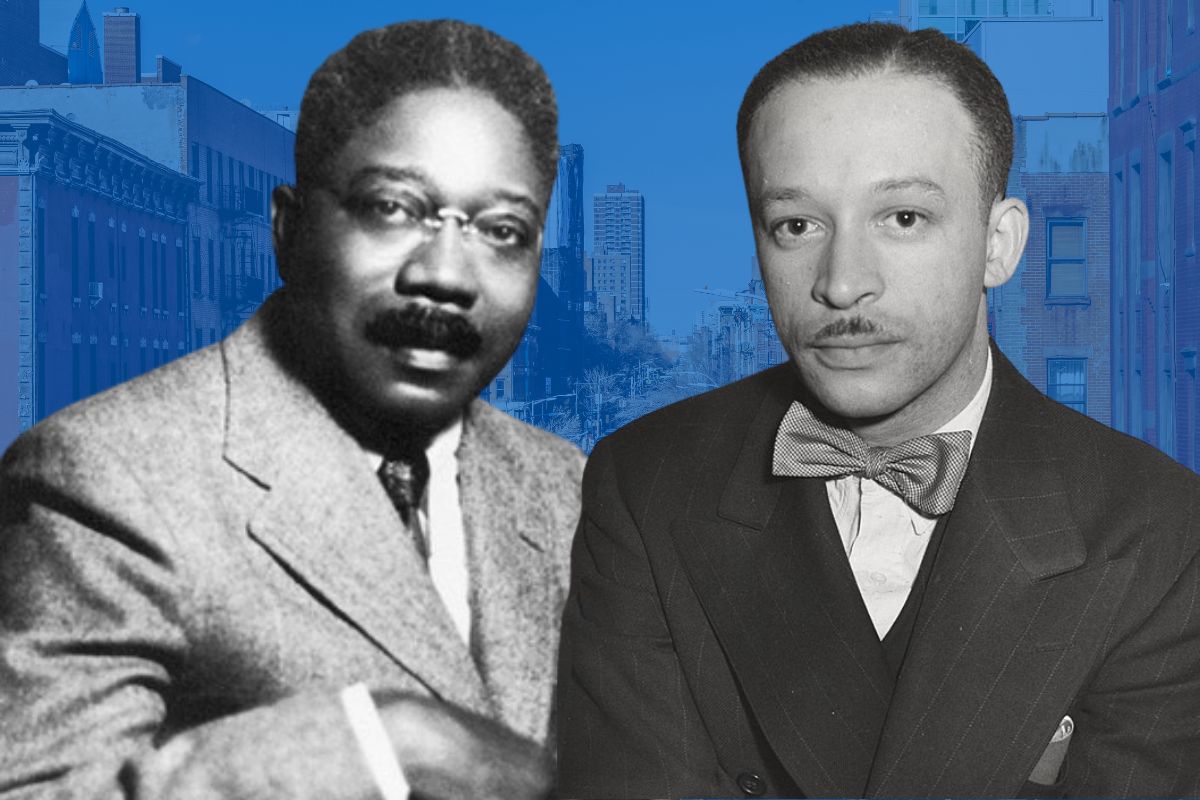

The Contributions of Charles Alston and Aaron Douglas

A recipient of TC’s first Distinguished Alumni Award in 1975, Charles Alston was born in Charlotte, N.C. in 1907 and his family moved to Harlem in 1915. By high school, Alston was nurturing a deep passion for art and won a scholarship to Yale’s School of Fine Arts, before ultimately choosing to attend Columbia University. He refined his skills during his tenure at CU, despite being barred from certain classes because of his race, and was ultimately awarded the Arthur Wesley Dow Fellowship to further his art studies at TC.

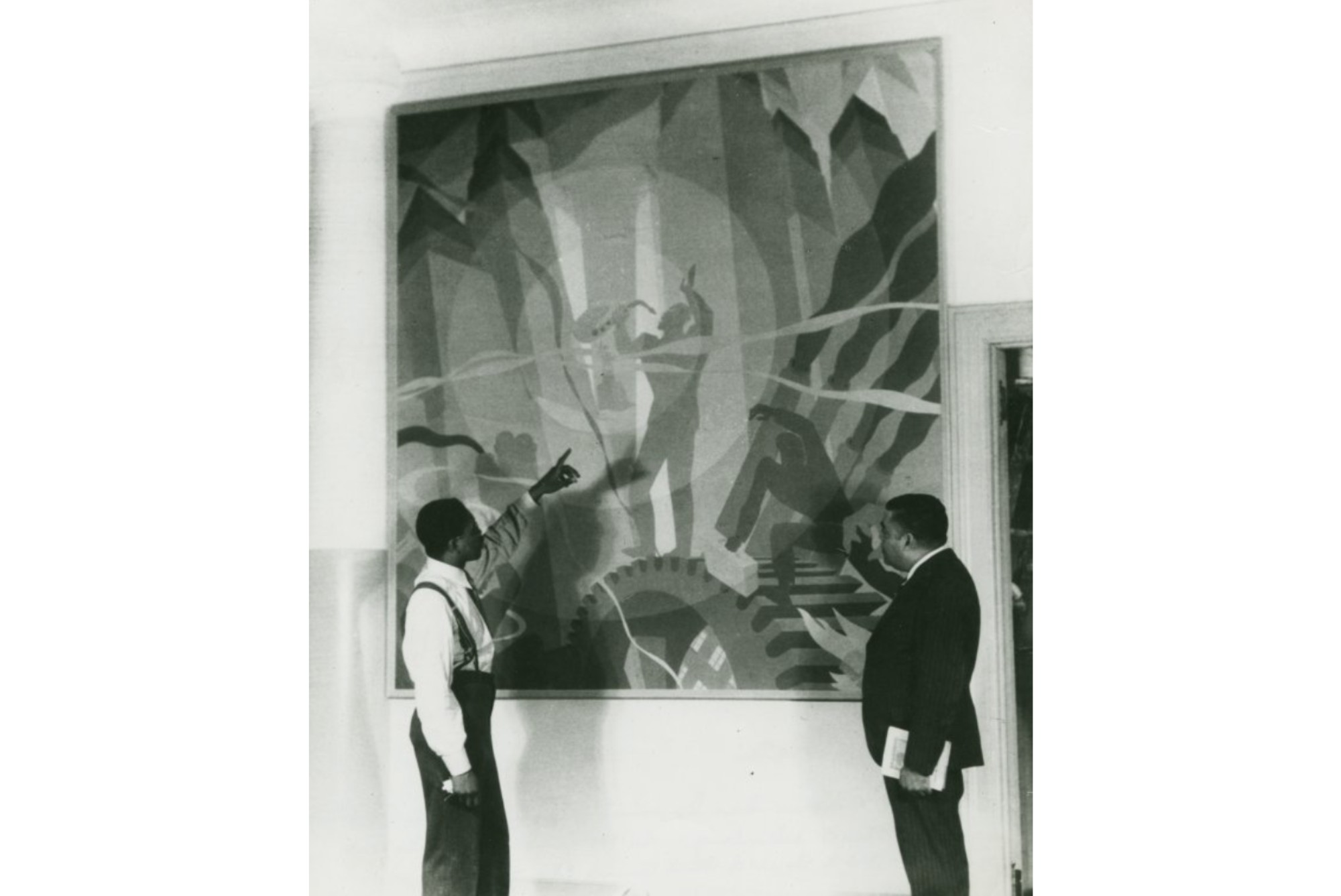

While at TC Alston’s professional career kicked off, designing book and album covers for the likes of Duke Ellington and Langston Hughes. As a sculptor, illustrator, muralist and portraitist who worked commercially and on personal projects, Alston’s oeuvre is incredibly broad, not only documenting greats like Martin Luther King Jr. but also the daily lives of ordinary Black Americans.

Throughout his long career, Alston frequently broke barriers — being appointed as the first Black instructor at the Arts Students League and the Museum of Modern Art. As an educator, he fostered new generations of Black artists using the philosophies of TC mentors John Dewey and Arthur Wesley Dow, as well as through the establishment of art collectives like the Harlem Artists Guild.

Aaron Douglas, a contemporary of and occasional inspiration to Alston, was born in Topeka, Kan. in 1899. While he inherited a love of art from his mother and graduated with a B.F.A from University of Nebraska in 1922, Douglas didn’t pursue art full time until 1925, when a stop in Harlem turned into a long-term stay after reading an issue of Survey Graphic called “Harlem: Mecca for the New Negro.”

Mentored by Weinhold Reiss, Douglas quickly became a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance, building close relationships with icons like W.E.B. Dubois and Zora Neale Hurston. His striking style, which combined elements of modernism and art deco with traditional African art, was incredibly influential. As the founder of Fisk University’s Art Department, Douglas was as dedicated to teaching art as he was to creating it. He earned a graduate degree from TC in 1944 to help achieve this goal. He served as department head, opening up the educational opportunities for countless Black artists in the South, until retiring in 1966.

Despite the incredible success Alston and Douglas achieved, it’s important to acknowledge that, as Black people in the 20th century, “they had many struggles to achieve a comfortable lifestyle and gain acceptance in the mainstream…this was mostly, if not all, due to racial inequities,” says Angela Gooden, a research associate at the Edmund W. Gordon Institute for Urban and Minority Education.

Considering that the fight for racial equity is still ongoing, achievements from the past may offer a blueprint for the future. “It's about digging through [the archives] to find what worked and what was successful…[then] taking from what these historical figures did and using it in our modern context,” says Walrond.

See works by Alston, Douglas, and dozens more at the Metropolitan Museum of Art now until July 28, 2024.