Summer frees up an average of 360 hours for kids across the U.S. And while day camp, soccer practice or piano lessons may offer parents brief refuge, summer vacation puts the pressure on families and begs the question: how much free time is developmentally okay for kids, and how should they spend it?

Enter play-based learning, a core component for child development and an academic focus for TC’s Nathan Holbert and Haeny Yoon, who offer actionable insights in honor of the playful possibilities of summer and the parents at the helm.

(Photo: iStock)

Don’t worry too much

Take a deep breath — free time can offer your child the opportunity to be creative problem-solvers in entertaining themselves.

“If [your kids] are sitting around, it's easy to feel like you are failing in some way, even if that's exactly where they want to be….Parents can give themselves a break,” says Holbert, Associate Professor of Communication, Media and Learning Technology Design, who hosts the Pop & Play podcast with Yoon. “These are totally reasonable things to be anxious about, but kids know how to play. You don't need to solve that for them…Give them a chance to be lazy and bored, because that's also an important developmental experience to have.”

Still, every child is different, acknowledges Yoon, Associate Professor of Early Childhood Education, who recommends parents stay attuned to the unique sensibilities of their kids to adjust how much structure they have. “It really depends on where the child is socially, emotionally, and intellectually and then their personal commitments and passions that they kind of want to pursue.”

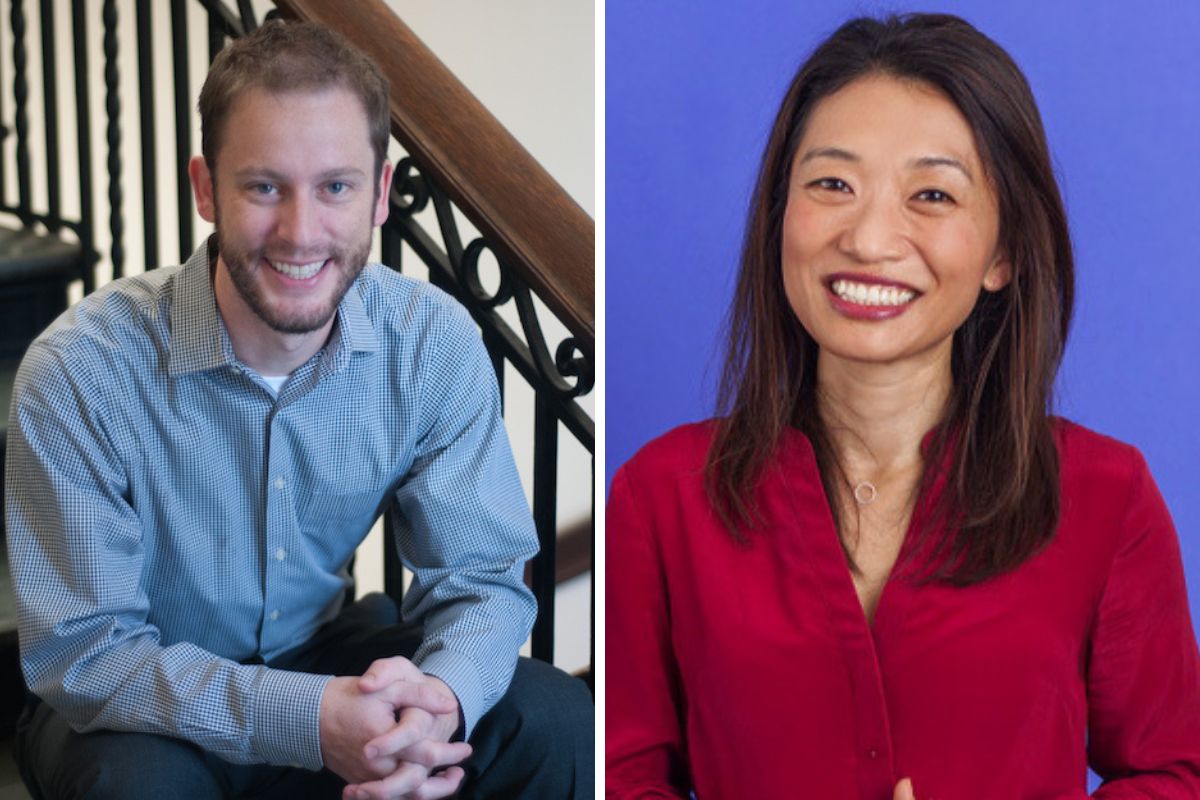

Nathan Holbert, Associate Professor of Communication, Media and Learning Technology Design, and Haeny Yoon, Associate Professor of Early Childhood Education, who host Pop & Play, a podcast on play and pop culture produced by the College's Digital Futures Institute.

Furthermore, parents can also take comfort in Yoon and Holbert’s belief that play is a developmentally complex process, and that attempts to cast certain types of play as “good” or “bad” with broad strokes don’t align with what the two have found through their scholarship.

“If we're listening to see if this play is valuable — if it helps them learn math, or if it's assisting their writing — then we can get so caught up and narrow-minded looking for that learning that we don't actually see or understand the whole context of [what play] is,” explains Yoon. “And it can be so delightful and really amazing, right, the things that children convey to us at their play.”

(Photo: iStock)

Offer scaffolded support through listening

Helping kids develop the tools to explore new experiences, learn a new skill, or even to entertain themselves involves guided constraints, explain the TC colleagues, whether it's through crafting, games or some other kind of activity in which the child has expressed interest.

“Listening is a great way to think about what scaffolds and supports that a child might need to get to the next step,” says Yoon. Citing her own recent experiences taking a book-binding class, Yoon explains that a good learning experience provides basic tools, methods, and techniques, “and then, when you have other flexible time, you have something to work from.”

Holbert likens the process of scaffolding to the steps involved in teaching a kid how to ride a bike: training wheels, holding the bike as the child rides, and then gradually letting go.

“People understand this basic concept of how to support learners, even if they're not an educator, because they're humans and they've encountered it so much in their own lives,” says Holbert, noting that there is no single magic formula for scaffolding all children. One can consider: “What does this child need? What kind of things would help them feel confident and help them take some minor risks here, help them be creative or do a thing where they can really express themselves? And then how can I give that to them, while also giving them the space to have their own kind of experience?”

(Photo: iStock)

Stay Connected

Get actionable solutions and bold expert insights for true change.

Straight to your inbox.

Play is important all the time, not just summer

Since play is a stress-reliever for both kids and adults, Yoon and Holbert see it as even more essential during the school year, when children have more to cope with and balance.

“People are so open to talking about play in the summer, because that's when it's ‘supposed to happen’,” says Yoon. “And Nathan and I firmly believe that play is equally important during the school year, when kids are trying to learn, grapple with things, care for their wellbeing, nurture conflicting tensions that we have with being busy and trying to maintain their sense of self. Kids are having anxiety over what's happening at school, but then also trying to be successful, make friends and then also trying to do all of these different things… I wonder about the seasonal time constraints related to the shifts when we think it is time for play and for work. And that happens for [adults] too.”