reposted from the TC Newsroom

Scanning 12 milk carton-sized boxes of someone’s personal papers and other memorabilia would be time-consuming under the best of circumstances. When the contents are a heretofore private trove from the apartment of the late education philosopher Maxine Greene, speed becomes beside the point.

“I just couldn’t help getting drawn into her writing,” says TC English Education doctoral student Beth Semaya. “I had to keep stopping to sit down and read.”

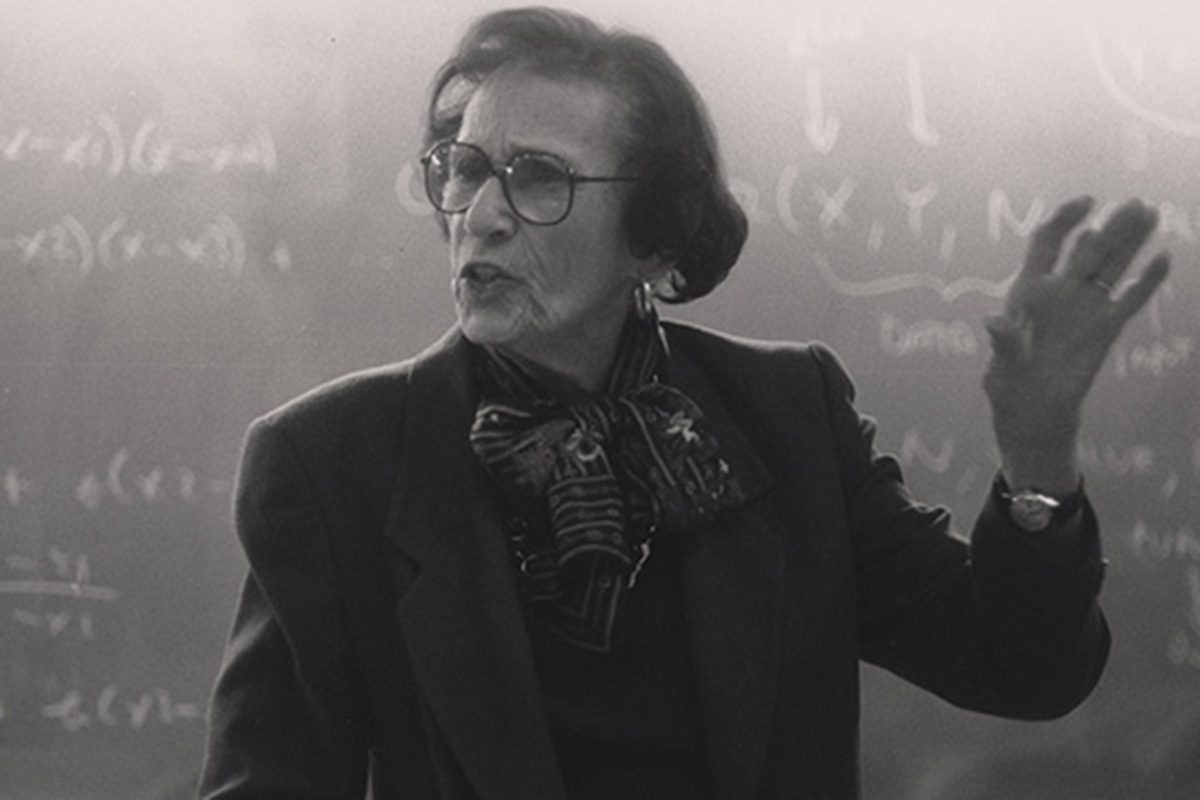

Under the direction of Janet Miller, Professor of English Education, Semaya and another English education doctoral student, Maya Pindyck, have spent the past two years immersed in previously unseen writings, letters and photographs of Greene, who approved the project (and all its contents) before her death in May 2014. Jennifer Govan, Senior Librarian at TC’s Gottesman Libraries, has also played a major role. Now the fruits of their effort – the M. Archive – can be accessed on PocketKnowledge, the Gottesman’s online platform. (The original hard copy materials have been archived in Columbia University’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library.)

“Maxine was a packrat – all of this material was stashed away high on her closet shelves or scattered amidst her walls of books,” says Miller, a longtime friend of Greene’s, whose scholarship (including her dissertation) has often focused on Greene’s work. The contents of Greene’s boxes included lengthy hand-written letters from the philosopher to her parents in 1936, when she traveled in Europe with her sister, Carol; “witty correspondences” with the presidents of colleges and universities; notes from Greene’s undergraduate days at Barnard (“Some might not realize that she was a history major and a philosophy minor there,” Miller says. “She ended up in education because the only time of day she could attend graduate school was from late morning until mid-afternoon, when her young daughter was in school. That’s when she took her first course at NYU, one focused on history and philosophy of education”); the handwritten manuscript of an unfinished novel, one among what Maxine called her two and one-half attempts (“She was very clear that she did not want this archived – she thought it was terrible”); fragments of unpublished essays; and revisions upon revisions of many of her writings.

The latter make it clear that Greene, who famously said, “I am . . . not yet,” lived by those words. “One thing that comes across is that she worked in an iterative way – she never felt anything was done,” says Semaya. “Even when she was facing a hard deadline, you can see that she would have been very happy to keep going back and revising.”

Yet everything in the M. Archive (so named to distinguish it from a more random collection of papers created on PocketKnowledge some years ago), down to the most casual exchanges with friends and colleagues, is written in Greene’s unmistakable voice – with “extreme deliberation; there’s never any sense that something is a first draft” – and all reflect Greene’s omnivorous reading appetite, with heavy emphasis on fiction writers, including Wallace Stevens, Toni Morrison and Tillie Olson, among many others, as well as on the philosophers Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus, Maurice Merleau Ponty, Alfred Schutz and, perhaps most pervasively, Jean-Paul Sartre.

“She was a declared and unwavering existential phenomenologist, and a fairly avid follower of popular cultural phenomena,” Miller says. “She once asked me if I ever watched ‘Dancing with the Stars.’”

Beth Semaya, whose dissertation is focused on the professional learning experience of novice teachers but is framed by Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, and Pindyck, who is writing hers on the pedagogies of poetic inquiries ("what does it mean to think, learn and know through poetry?") had the good fortune to attend the famed salons that Greene held in her apartment right up until her death. Yet both say the experience of scanning her papers page by pagehas been invaluable.

“I felt so constantly surprised and inspired by her,” says Pindyck. “Her ideas touch on aesthetics, literature, poetry, philosophy, and she has this incredible ability to move across disciplines and bring it all to bear on almost any question” – including, Semaya adds, some that most people hadn’t thought of yet.

“She was incredibly forward thinking, especially about education,” she says. “She anticipated surveillance culture in schools, teacher accountability, the role of technology – she could see it coming before any of it was explicit.”

For Miller, the archiving project is only one facet of what, over time, has become a substantial part of her life’s work. She is midway through writing a book, Maxine Greene and Education, that will be part of the Routledge invitational series on renowned educators’ “Key Ideas,” and then will work on a biography – partly to fulfill a promise to Greene, but partly because “I can’t imagine students not knowing about the work and life of Maxine.”

Now they can at least begin to.

How to access the M. Archive:

Go to:http://pocketknowledge.tc.columbia.edu

User will need to have a “uni”/be a member of Teachers College and/or Columbia University and have created an account in PocketKnowledge.

- Type “Maxine Greene” in the search box.

- Click the radio button for “All.” ("Pockets" should be highlighted below in red).

- Look for “Maxine Greene Archive” (on your right, after “Personal Writings”).

- Click on “View All” under “Maxine Greene Archive”

Outside researchers will need to follow the route for applying for access, as described here: http://library.tc.columbia.edu/archives.php