In this blog post, Dr Kryssi Staikidis, Art and Art Education Alumna discusses four thematic sections from her new publication Artistic Mentoring as a Decolonizing Methodology An Evolving Collaborative Painting Ethnography with Maya Artists Pedro Rafael González Chavajay and Paula Nicho Cúmez. Each of the four sections is introduced by the use of paintings as sites for teaching, for claiming Indigenous history, for collaborative ethnography, and for relationship.

Paula and Kryssi, collaborative ethnography, editing a video together in Paula’s painting studio, San Juan Comalapa, 2011

"This book discusses Maya artistic mentorship as a decolonizing methodology that reveals Indigenous perspectives about teaching, artistic processes, and the use of the visual to protect Indigenous cultures in contemporary contexts. Nevertheless, as the evolution of transformative approaches to documenting the work and representing the work attests, this is a complex, messy, and encumbered process never free of an economic power dynamic, classism, racism, and discriminatory practices endured by the Maya communities for centuries. I have been rightly questioned about the purpose of the work, who benefits from the work, and how the content of the work should be and should not be represented. The transformations of the work over time are my attempt to respond to such questioning by challenging myself and taking action to change the work to benefit the Maya consultants in the ways that they state are beneficial to them".

Part 1

The Artist as Mentor: The Mentoring Relationship as a Teaching Method and Paintings as Didactic Tools

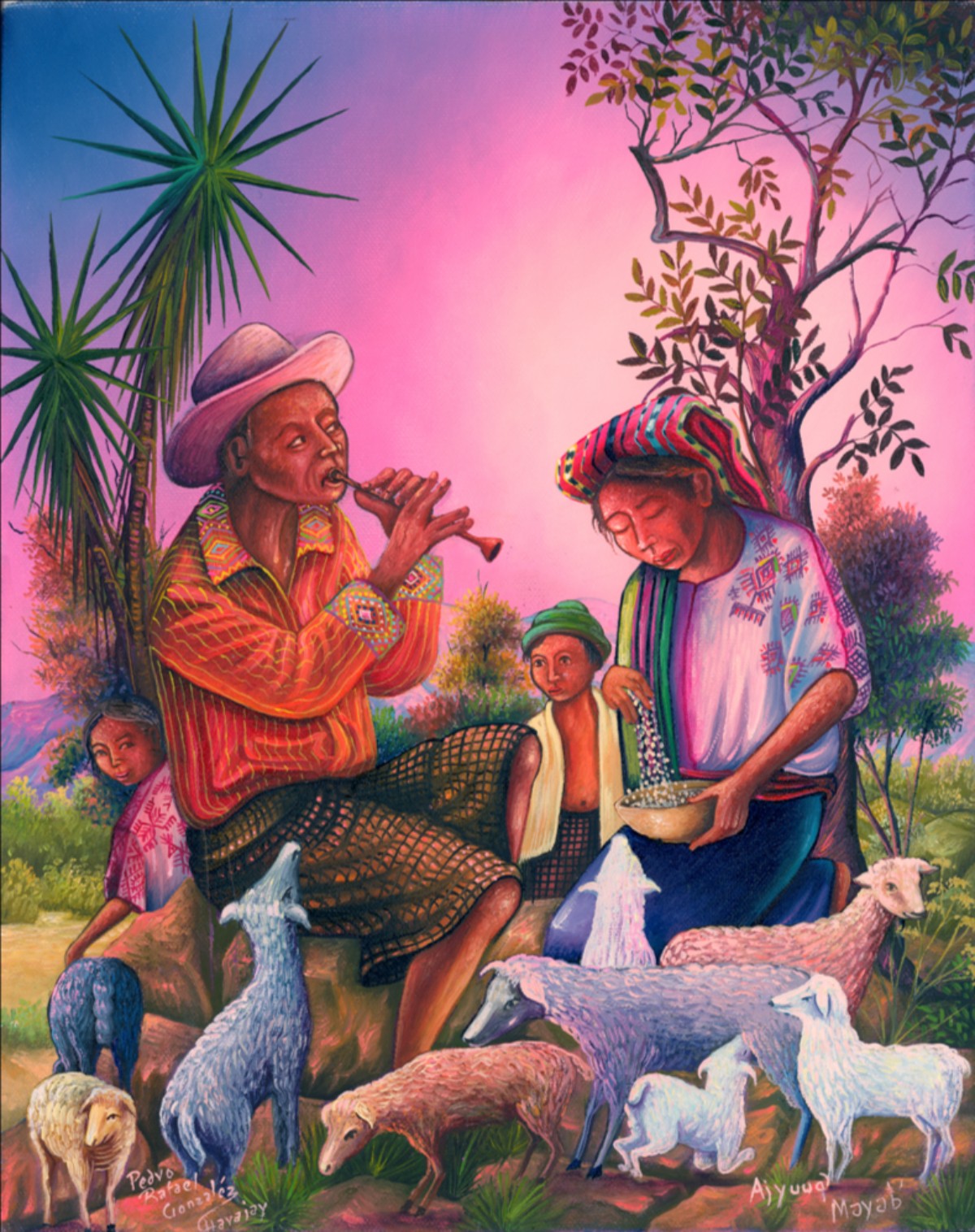

The Artist as Mentor focuses on the painting lessons taught to me by Maya mentors and the characteristics of their teaching. In addition to the role of the artist and the teaching relationship, artworks too have their own role and perform many functions. Paintings are used to teach, and in some ways can be considered teachers in their own right, both as didactic tools and as sites for understanding cultural customs.

Pastor Maya (Ajyuuq’ Mayab’), Pedro Rafael González Chavajay, 2002, Oil on Canvas, 11" x 14"

Part 2

The Artist as Historian: Paintings as Historical Documents, Sites for Cultural Transmission, and Platforms of Protest and Resistance

The Artist as Historian, reveals that the Maya artists who taught me and their students see themselves as historians whose role is to preserve Maya cultural traditions, values, and beliefs in the form of paintings, which become evidence for future generations. Artworks as objects, therefore, transmit cultural history and educate young people as well as cultural outsiders about the greatness of Maya cultures. Pedro Rafael González Chavajay, as well as his students and the artists with whom I spoke, consider paintings historical documents that embody traditional dress, the importance of connection to land and place, and a record of ancestral traditions.

Massacre in Atitlan: December 3, 1990 (Massacre in Atitlan), Pedro Rafael González Chavajay, 1993, Oil on Canvas, 36" x 54

Part 3

The Artist as Ethnographer: Collaborative Ethnography, Decolonizing Research Practice, and the Ethics of Representation

The Artist as Ethnographer, focuses on the ways that the Maya mentors, as experts in painting, guided me, their student, to participate fully in the collaborative process of making artworks on the same canvas.

A finished collaborative painting, Nuestra Amistad (Our Friendship), illustrates community life, as collaborative paintings are didactic works, visual sites for learning about Maya customs. So, in addition to the role of the artist as ethnographer, the role of each artwork was a site for collaborative ethnography and as such a visual platform for arts-based research.

Nuestra Amistad (Our Friendship). Paula Nicho Cúmez & Kryssi Staikidis, 2011, oil on canvas, 24” × 36”

Part 4

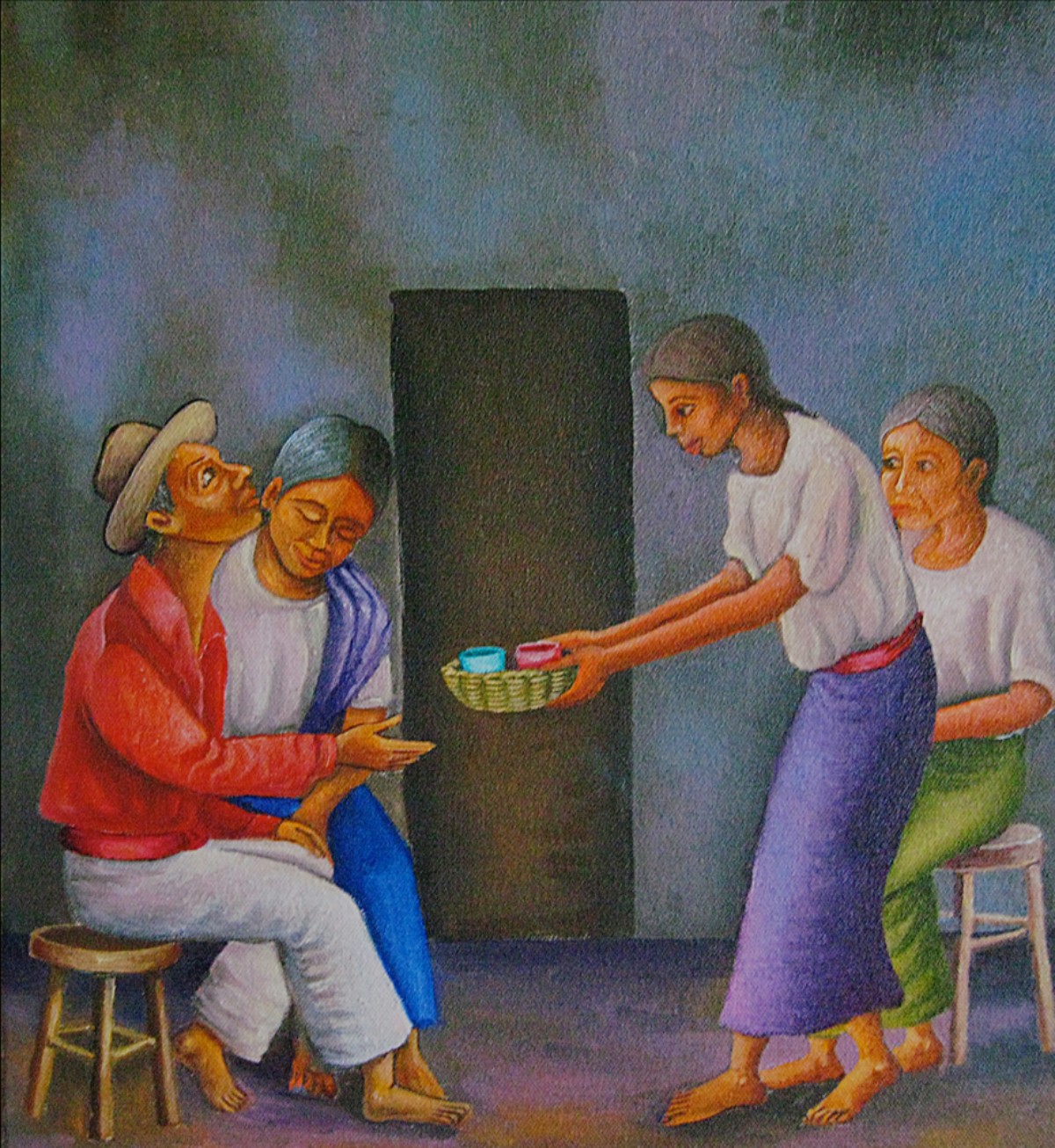

The Artist as Teacher: Transformations of the Academy and the Artist/Teacher

The Artist as Teacher, focuses on the mentoring relationship between teacher and student, the most important channel for genuine learning in the two Maya households where I studied painting. The painting itself also becomes a site that reflects that shared relationship, as it testifies to the trust and caring between teacher and student.

“La Consolación” (Condolence), Pedro Rafael González Chavajay & Kryssi Staikidis, 2011, Oil on Canvas, 12.5” x 14.5”

Positionality remains one of the central ethical challenges of this project, because as a non-Indigenous person, I am a cultural outsider educated in a system with deep roots in the worldviews responsible for the material, intellectual, and spiritual violence of colonialism. Therefore, I examine my own ethnographic research in the hope that young researchers become aware of the complexity of decolonizing methods and the importance of rigorous introspection. Four broad areas are examined: language, dismantling concepts, confidentiality, and representation. In addressing ethical issues of ethnographic research, the ethics of research and representation become a conscious topic of self-reflection.

This blog post complements episode 4 of our podcast, Malted. On the episode, we invited Art and Art Education alumna Dr. Kryssi Staikidis and Doctoral student Carina Maye to discuss Dr. Kryssi's new book Artistic Mentoring as a Decolonizing Methodology: An Evolving Collaborative Painting Ethnography with Maya Artists Pedro Rafael González Chavajay and Paula Nicho Cúmez. Listen to the podcast below.