Program History

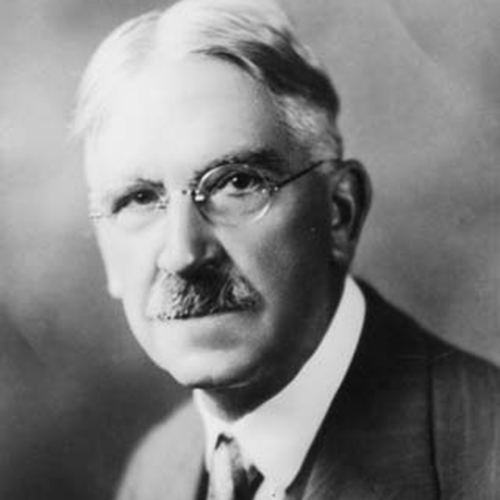

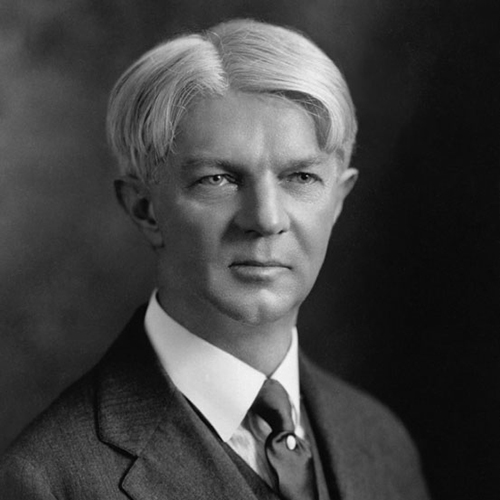

Teachers College was founded in 1887 as a professional school for education and the health sciences. At that time, all students at the college—current and aspiring teachers, principals, nurses, counsellors, and nutritionists—undertook a program in liberal studies. Early on, students were required to register in a year-long foundations course, in which they would consider the impact of social, political, and economic forces on education and the health sciences using foundational disciplines such as history and philosophy. In later years, students were required to select one of numerous foundations’ courses offered by the Department of Philosophical and Social Foundations of Education. This Department included such philosophers of education as William Heard Kilpatrick (1871–1965), George Counts (1889–1974), John Childs (1889–1985), and Jesse Newlon (1882–1941). All of them were close students of John Dewey’s (1859-1952). They sought to develop Dewey’s philosophical ideas as they explored their implications for educational practice. Several decades later, the Department of Philosophical and Social Foundations was partitioned into a range of programs, one of which is the Program in Philosophy and Education that we have today. Over the years, its faculty have included Philip H. Phenix, Maxine Greene, Jonas Soltis, René Vicente Arcilla, and Christopher R. Higgins.

In many respects, Kilpatrick and Greene bookend the history of this program. Kilpatrick is known for “The Project Method,” which became highly influential in progressive education. He adopted the term “project” to suggest “something projected” because he was convinced that present activities have a tendency “to suggest and prepare for succeeding activities” which bring us into wider interests (see Cremin, 1964, p. 330). Like Kilpatrick, Greene conceived of the human person as projected forward into an unknown future. While Kilpatrick stressed purposeful activity, Greene stressed creative imagination. She argued that freedom consists in envisaging new possibilities: namely, to look at one’s surroundings as if they could be otherwise. It is, to use Greene’s language (inspired partly by her study of Dewey), to be wide-awake.

Current faculty in the program are David T. Hansen and Megan J. Laverty. They have built upon and transformed the invaluable inheritance bequeathed to them by previous faculty and students. For example, through their research, teaching, and service, they have advanced the cause of including philosophy in the K-12 school curriculum, an important venture in light of the significance of an educated, thoughtful citizenry in a democracy. A new course on ‘Philosophy Goes to School’ will soon be offered. Faculty have also addressed educational and political pluralism in the world today by examining perspectives from ethics, aesthetics, civics, cosmopolitan theory, and more, and by creating new courses such as Philosophies of Education in the Americas I (North America) and II (Latin America), and African-American, African, and Africana Philosophies of Education. Most recently they have co-edited a landmark, five-volume history of Western Philosophy of Education, which includes entries on a great many influential thinkers and movements across the ages, as well as entries on the relations between education and democracy, race, gender, class, and other social factors.

Throughout its history, the Philosophy and Education program has avoided becoming mired in the “isms”, while remaining alert to contemporary debates. Faculty and students have felt drawn to large and time-honored questions. It is the sheer force of these questions that brings individuals to this historically significant program.

Click on the photos below to learn more about some of the distinguished faculty who have taught in the Philosophy and Education Program.