A recent publication, Transitional Justice and Education in Colombia: The Perspective of Youth, authored by a diverse team of researchers led by Prof. Garnett Russell, offers a groundbreaking analysis of the intersection between transitional justice (TJ) and education in post-conflict Colombia. This policy report was recently launched through an online event at Teachers College and aims to shed light on how schools play a pivotal role in fostering peacebuilding and addressing structural inequalities rooted in decades of armed conflict.

The report was co-authored by the research team, including ICEd faculty, current students, and alumni: Paula Mantilla Blanco (PhD ‘24), Daniela Romero Amaya, Sara Pan Algarra, Ángela Sanchez Rojas (MA ‘24), Victoria Jones, Leonardo Arevalo Roajas, Paola Abril, Tatiana Cordero Romero (MA ‘24), along with collaborators Juan Camilo Pimiento and Carolina Valencia from the Fundcación Memoria y Ciudadanía. This research focuses on Colombia’s educational response following the historic 2016 peace agreement following more than fifty years of ongoing violence and internal displacement. By examining qualitative and quantitative data from 12 secondary schools across Bogotá/Cundinamarca, Antioquia, and Norte de Santander, the study prioritizes youth voices, capturing their experiences with TJ themes such as justice, peace, and violence.

The report addresses two critical questions: (1) how extensively TJ has been integrated into educational institutions across diverse regions, and (2) how students and teachers interpret and engage with these concepts. This work highlights the complex, multifaceted relationship between education and TJ, positioning schools as more than just transmitters of historical knowledge but also as key actors in the promotion of sustainable peace. The authors emphasize that understanding youth engagement with TJ concepts can have long-term implications for fostering reconciliation and addressing deep-seated societal inequities.

By centering the perspectives of youth in urban and rural Colombia, this study not only adds to the growing body of scholarship on education and TJ but also underscores the potential of education systems to be transformative agents in post-conflict settings. The findings are particularly relevant to policymakers, educators, and researchers looking to create frameworks that support transitional justice and peacebuilding worldwide.

The report can be accessed here:

Below is an interview with Prof. Garnett Russell discussing her work on Transitional Justice:

Interviewer (N): Can you tell me about the background and context of your research?

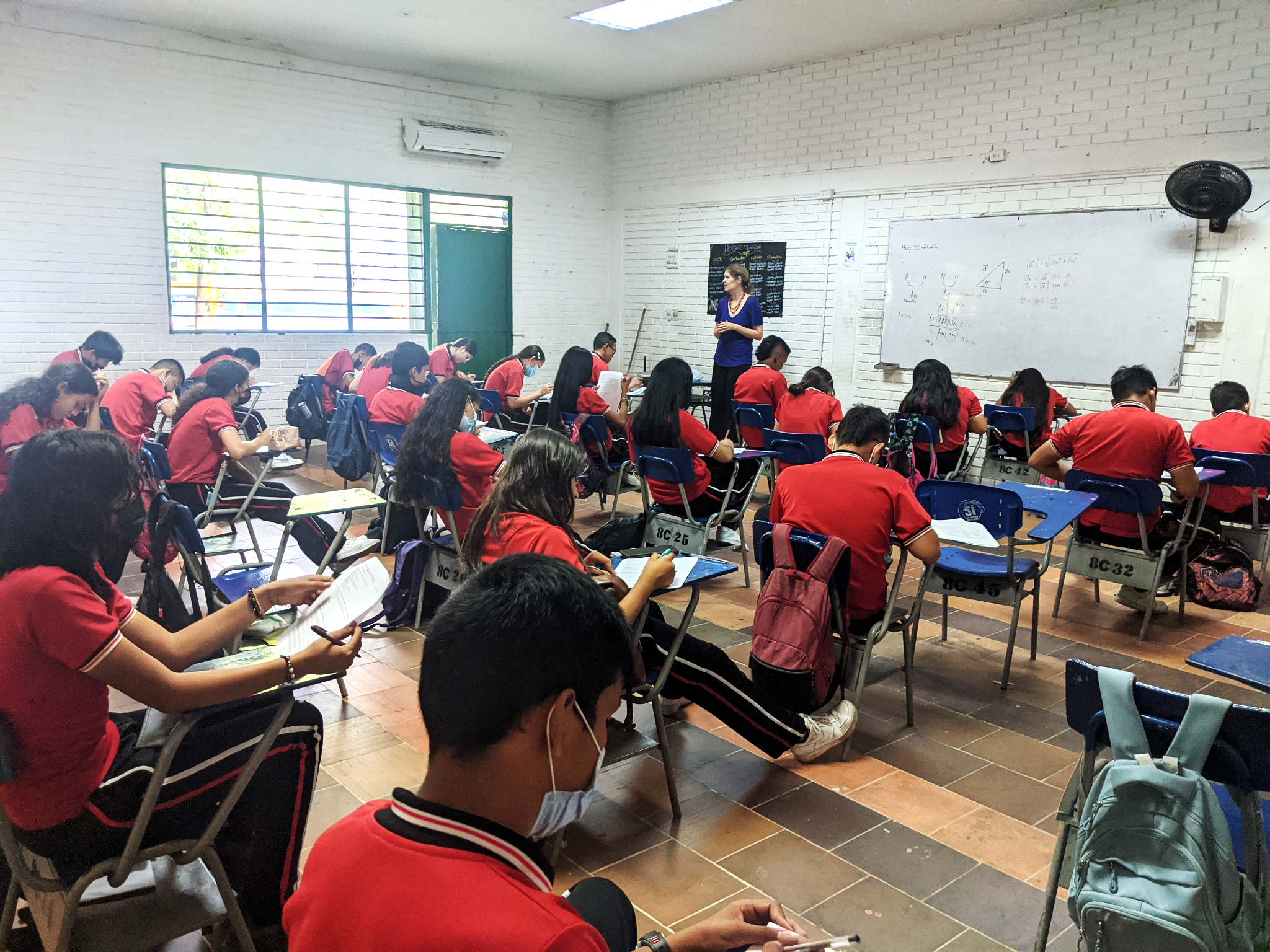

Interviewee (G): The research began in 2018 after Colombia signed the peace agreement in 2016, which aimed to resolve over five decades of armed conflict. The main data collection occurred in 2022, across three regions: Antioquia, Norte de Santander, and Bogotá/Cundinamarca. These regions were chosen to represent a mix of public and private schools in urban and rural areas with varying degrees of exposure to the conflict.

N: What were the primary research questions you were trying to answer?

G: We wanted to explore the role of schools in peacebuilding and the promotion of transitional justice in Colombia. Specifically, we focused on how peace education and transitional justice were integrated into school curricula and how these efforts related to the broader peace process in the country.

N: Can you describe the methodology you used to gather data?

G: Yes, we used a mixed-methods approach. This included surveys with approximately 2,000 students, interviews with 190 students, and observations of classroom practices. We also conducted interviews with teachers and other local community actors to understand how they approached peace education and the transition from conflict.

N: What were the key findings of your research?

G: The key finding was that many schools had already been actively promoting peace education, social-emotional learning, and citizenship even before the formal peace agreement was signed. However, there was a gap in connecting these efforts with transitional justice mechanisms like truth commissions or memorials, which were critical components of the peace process.

N: What were some of the challenges you faced during the research?

G: One of the biggest challenges was security, especially in rural or conflict-affected areas, which made it difficult to access certain schools. Additionally, some schools were hesitant to engage in discussions related to transitional justice, fearing potential controversies or sensitive reactions from students and parents.

N: Looking ahead, what are your hopes for the future of this research?

G: Moving forward, I hope the research can contribute to a deeper understanding of how education can play a role in supporting peacebuilding and transitional justice. It’s important to connect peace education with the broader frameworks of transitional justice to help schools become more integrated into the peace process. I also hope the findings can inform educational policies not just in Colombia, but in other post-conflict societies as well.